I started learning Bharatanatyam in 1988, when I was six years old. Looking back, it feels like beginning to learn to dance was, somehow, a key moment in my personal gender and sexuality history. It was the time I started, formally, to condition and train my body to move in specific ways. Earlier, in school, a teacher who was recruiting kids for an annual day dance had rejected me saying I was not flexible at the waist. It hurt deeply to be told that my hips didn’t sway enough. I wanted to sway and sashay, I wanted hips like those women had in the Hindu epic representations in Amar Chitra Katha comic books. I wanted breasts too, but it took years for that desire to grow and then become something of an angst.

From then on, all I wanted was to be able to move gracefully. Ironically, a few years later, responding to taunts and jibes, I struggled with suppressing the same dance-conditioned movements of my body that I had once desired without reservations. I realized that I was supposed to move differently in different spaces, and that I needed to be very vigilant and not mix up genres. Definitely no hipswinging on school corridors. It would be a social mistake. When I did make the mistake and was called out on that, there was often some kind friend or teacher who would offer an explanation: “He can’t help it. He is learning classical dance.” Dance thus was also an explanation: I couldn’t help being a little ‘effeminate’; I was ‘contracting’ dance.

I grew up in Kumbakonam in a Tamil Iyengar family, in a Brahmanical cultural field animated by Carnatic music, Sanskrit and Tamil hymns on lips and tape recorders, and narratives of myths and legends, and gods and goddesses all around me. All I had to do was reach out and touch them. They were the objects that orientated me. My parents held on to religion rather loosely. There certainly wasn’t any orthodoxy; far from that. But the cultural landscape I grew up in was certainly a Brahmanical one, with the specific inflections of a Vaishnava ethos. Later, my views on caste and Brahmanism added some necessary complications to my relationship to this cultural inheritance, and I continue to hold the messiness of these connections together.

Both as part of the textual education that came with serious training in Bharatanatyam as well as because of the Vaishnava cultural scape I grew up in, I read more of her works later. In her poetry, breasts heave and grow heavy with the burden of separation from her lover/god, and bones melt away in the heat of her anguish and suffering. In the world of her supple words, she doesn’t merely grow sleepless; her eyelids fail to meet each other and so her spear-like eyes grow weary. In her eyes, Krishna’s curly locks of hair become a tight swarm of bees vying to get closer to his flower-like face. It was a world where there was no separation between desire and devotion. Everyone kept saying it was spiritual stuff, and the poems were certainly part of the religious literature of the community. But it was all intensely physical and deeply felt; in bones that wither, brows that droop with weariness, eyes that glaze with sleeplessness, and in breasts that swell in joy at the prospect of union and sag with heaviness and the pain of continued separation. For a queer boy welling up with forbidden desire, it was all unimaginably exciting and comforting.

It was also in the year 1988 that B.R. Chopra’s TV series ‘Mahabharat’ started airing on Doordarshan. I developed a secret crush on Arjuna.I think it was, actually, a crush on the actor who played Arjuna, Feroz Khan, but I am not going to split hairs here. My most favourite episodes of the series were the ones where the Pandavas are in the thirteenth year of their exile, living in disguise in Virata. Arjuna transgenders into Brihannala, an incredibly talented dancer, musician, a teacher of war craft, all rolled into one. This visual representation, however exaggerated and problematic, couldn’t have come at a better time as far as I was concerned. I didn’t know why Arjuna’s temporary transformation appealed to me so much then, but it made a lot of sense later.

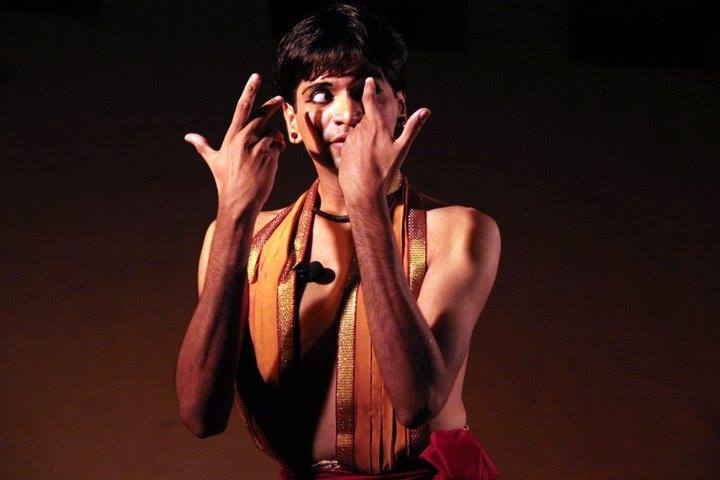

My desires for a differently gendered body were not continuous and unrelenting. They happened in intense spurts and always left me quite contented with the body that I had. Brihannala became a kind of reference point or an ideal type for that kind of temporary and reversible possibility. With that, and the queer possibilities I already saw in the friendship between Arjuna and Krishna, it was all heady and validating. This was what led me to create a performance piece on Brihannala three years ago. It is a deeply personal piece, and I use storytelling to retain and calibrate that personal narrative, and it takes me to new places each time. The last time I performed it, which was a little over a month ago, I thought of Brihannala as a sign for some kind of excess, either that which is overflowing the limits of necessity, or that which is leftover. Like a metaphor for what I perceive as my gender and sexual excess, a language for that which doesn’t quite add up in me and for which the identity tags that are currently available are not quite enough. Interestingly, Andal’s poetry has now started seeping into my Brihannala narrative. I cannot quite account for it, but it is nice to have some sort of a language to talk about those parts of me that don’t quite add up neatly and always leave a tasty residue, a strong and pleasant aftertaste, a lingering tingle that makes me shiver sometimes.

Pic Source: Aniruddhan Vasudevan, Facebook

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।