I read The Failed Radical Possibilities of Queerness in India more than a year ago and it still makes me a little uncomfortable. For all the complications the narrative offered about gender, parental pressure, sexuality, love, and upper caste forums reaching out to Dalit-bahujan collectives, one line stuck with me: “What can I say about my own role? Yes. I was angry. Yes, I muttered something finally that I no longer remember. But I also didn’t mention that my lover and partner – the person who I lived with and who I could not imagine life without – was Dalit”. So much so that I would send this piece to my (potential) partners/(intimate) relationships to point that they should never use me being Dalit to justify their intimacy with my caste (and not their own), or honestly, to feel that they deserve a trophy for breaking caste-barriers (I think all of us have a tendency to give our actions much more meaning than they deserve).

Another piece, The beautiful feeling of falling in love with a Bahujan Ambedkarite, made me a little nervous as well. I started feeling anxious after reading this. What is this “beautiful feeling that we share when surrounded by those like us”? Perhaps, I was sad, more than anxious. I have never really known that feeling with ‘people like me’. My relationship with caste is very intimate with the relationship with my family, which is nowhere near to what this article said. The family of ‘people like me’ (I doubt my parents even know the term ‘Ambedkarite’) doesn’t really love the people like me. What was wrong with me? Why do I need to dissect everyone’s experiences and reflections? Now, before you scream ‘male privilege’, as I write this, I realize that the experiences of the above-mentioned pieces I am looking at opening up, are of women; their experience to love, desire. And as much as I want to tread carefully while writing this piece, I don’t want to. I want to discuss how complicated all of our relationship with oppression is.

I think we fail to realize how deep the idea of tokenism runs within us. I have known many friends/acquaintances who would use my queerness and sexuality to win an argument about homosexuality, or to escape the label of prejudice (no matter at what institutional or social level). Similarly, people use the fact that they have a dalit/muslim/adivasi/trans/disabled friend as an accessory. But recently at an event (of Dalit women by Dalit women), on pointing out how sexuality and queerness is neglected in Dalit organizing, the answer made a reference to knowing/being friends with a queer-Dalit friend. The assumption that, making such a reference exempts one from being called out on assuming and putting ‘doing sexuality’ on queer identified persons/visibly queer individuals, got me thinking how the referencing hits you in the most unexpected places. From civil society organizations using your identity for their international funders’ portfolio, to friends, family, partners, mentors etc. using you as evidence, ‘identity politics’ is messed up indeed (because hey! They are not the ones doing identity politics right? It’s you! Why? Because you brought it up!).

My intimate relationships have been with two men. Both of whom happen to be upper caste. Before submitting this piece, I thought I would ask both of them, how me reflecting on my relationship with them would make them feel (do they teach researchers in institutions about self-reflection as ethics of methodology?). From a shoulder shrug to a furrowed brow (I admit that I don’t have a large sample to be drawing these reactions from), I thought that I should offer showing them this piece before I send it to the editors. How is this any different from the two pieces I talk about above? Am I also not using these two men as an object of analysis to be reflected upon? I don’t know. To what extent are we allowed to talk about others vis-à-vis ourselves? I ask these questions particularly in the context of anti-caste struggles making a severe attempt to undo appropriation and misrepresentation. Do these standards only apply to upper caste individuals talking about us? Prompted by this enquiry, I googled ‘inter-caste love’. Tips on How to Convince your Parents of Your Inter-caste Love, solving problems related to inter-caste marriage by ‘chanting of certain mantras’, and dilemmas about parent’s acceptance filled my screen. Violent reactions to inter-caste relationships, however needs no googling. Khap panchayats, mob lynching, moral policing, habeas corpus petitions are quite synonymous with inter-caste couples. How do I then talk about my desires without talking about the violence of what that desire (in an inter-caste context) has meant for million other ‘dalit’ desires?

A huge part of my relationship with the caste(s) other than mine, has been if I subconsciously seek friendships and intimacies with castes other than mine. Am I trying to escape mine by living it through others? While I do seek those friendships and intimacies, I am also extremely insistent on being ‘Dalit’. One of the common responses in many different kinds of relationships is how people (upper castes) are insistent on telling me that they/or their families don’t believe in caste. The very reason that they don’t go around asking people’s caste (and because they never asked mine!) is because they never grew up in a family which was insistent on caste. I guess these sentences become important to establish that they (upper castes engaging with me) are not like others. I, on the other hand, grew up in a family (much like many other lower castes) where we are reminded again and again what our caste means socially and politically. Lack of discussion or insistence on caste in households, therefore, isn’t a sign of not caring but a sign of you benefiting from it.

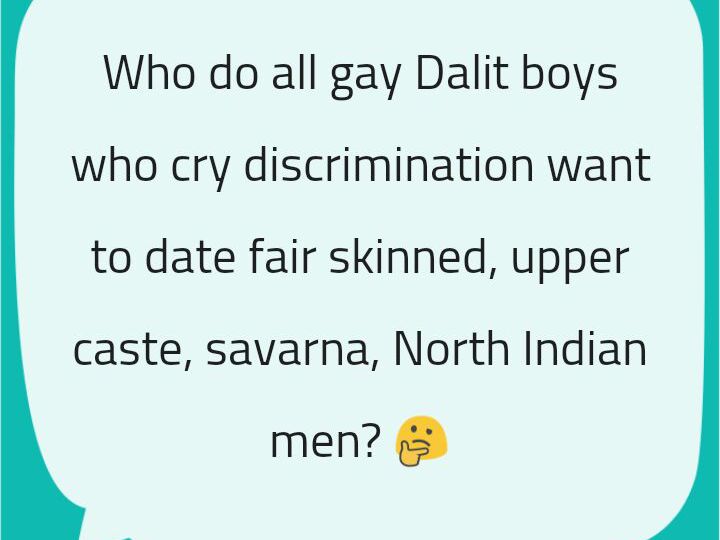

Therefore, being ‘Dalit’ in an inter-caste relationship isn’t just about breaking the norm, or ‘crying about discrimination’ (as our anonymous friend on Sarahah calls it), but about citing our identity which empowers us. To remind ourselves, more than others, what it means to be constantly in relationship with oppression and love. To not feel the burden of teaching you caste, whenever you doubt your own relationship with your caste, or validate your journey to realizing what anti-caste means.