“Just like any woman, … we weave our stories out of our bodies.

Some of us through our children or our art; some do it just by living.

It’s all the same.”

– Francesca Lia Block

After checking my vitals, Grace, my much-loved acupuncturist, looked at me with concern in her eyes. I had walked very fast in searing mid-June heat to her office, just over a mile from my home, and arrived hot and sweaty for treatment on my lower back. Grace didn’t mind the sweat. It was my cold belly that concerned her.

“How are your periods these days?”

“They’ve been mostly regular but since last year, they’ve been becoming erratic.”

“Your chi flow is uneven. There’s a lot of heat in your body and your oestrogen levels seem to be off. And I know you haven’t been sleeping well for some time now… I think we should treat this aggressively for a few months and see what happens. How old are you?”

“Thirty-eight.”

“Ah, yes, so… But maybe it’s too early for you… Let’s treat and see what happens.”

I felt a jolt through my body, the foggy-headedness that accompanies a steamy New York summer’s day quickly lifting. I knew what Grace was referring to. As I lay on the treatment table, I tangled with my feelings about the suspected prognosis. I felt some grief, a sense of loss, the likes of which one would feel on the cusp of any rite of passage. But I was not devastated. In some ways, I was relieved.

I love children and have at various times in my life flirted with the idea of adoption. But I have known since I was a child that I did not want to birth children. I have never been vague or ambivalent about this decision. I have never minced my words nor veiled my attitude about motherhood. I have been consistently clear and concise that this is not my calling. It’s not that I don’t value it or have ‘more important things to do’ with my life. I simply have no desire to bear children and it is not for want of experiencing pregnancy. I was pregnant in my late twenties and did not enjoy one moment of it. When I miscarried, I mourned for the soul that would have incarnated through me but I felt tremendous relief. For me, and many other women like me, my creative function can be expressed in a multitude of ways that may never involve my reproductive capacity.

When asked – confronted, actually – about my maternal status, I have been met with equal levels of criticism, gainsaying and disbelief from people known and unknown: “But why?!” “Really? Are you sure!” “Ah, you still have time! Maybe you’ll change your mind?” “Well, clock’s ticking! You better get a move on before you lose the opportunity altogether!” “Oh, but a little Remy would be so cute!” “But look how great you are with children! You’re a natural!”

And this: “It’s when you have children that you really learn about unconditional love!”

Despite my outward confidence, my belief in my right to choose how best to live my life, it is the continuous and often relentless questioning about my maternal status that serves to undo me. It entails such a profound denial of personhood that I really wonder how free we women are to be who we want to be. The subtext seems to be: womanhood is synonymous with motherhood.

A woman with children is more woman, and so I, childless, am less than. In that context, a woman’s personal wishes/choices seem to be neither here nor there. Any other contributions we make to society are cancelled out by our unwillingness to participate in womanhood’s most sanctified role. It would seem to me that despite the significant gains made by and for women, the myth of Motherhood continues to be used – collectively and interpersonally – as a subtle weapon of control, of policing women’s function in society. It is yet another location in which we are reminded that our biology is the beginning and end of who we are and what we can contribute to the world.

If the growing popularity of the NoMo (Not Mother) movement is any indication, I’m not alone in feeling these sentiments. And according to various studies and reports, more and more women around the world are actively choosing to not have children. What does this mean for womanhood in the 21st century?

Though we live in societies geared towards families, the subject of motherhood is fraught. On the one hand there is the fact that too many women around the world – including where I live in the ‘enlightened’ West – do not get the pre- and post-natal care they need. Outside of a few remarkable countries, maternity leave is abysmal, necessitating that ‘working women’ return almost immediately to the workplace or quit their jobs. Not to mention that reproductive justice and appropriate women-centered health care is hardly the norm. It is additionally by and large women who are the primary caretakers in society, not just of children but elders too. On the other hand, society tells us we have a duty to procreate. It’s as if women who choose not to bear children are straying so far from the natural norm that our actions could serve to ultimately upend the human race!

My mom was made for motherhood. She raised my younger brother and me by herself, making ends meet by cleaning neighbours’ homes and taking care of other people’s children. Because cash was always short, I know she often went without in order to provide for us. Despite how difficult conditions were, there was a constant flow of lost souls passing through our kitchen – young people who’d left home early or were kicked out and needed a bite to eat and a sympathetic ear. My mother still talks about how much joy she had in carefully choosing our names, in exposing us to the world at large, wanting to make sure we had the best of all opportunities. She would scrimp and save to send us on trips overseas each year, to pay for language, sports and dance classes and expensive dental work, so that we could live out the fullest expression of who we are. And if she could have had more children, she would have made room for them too. It’s as if despite the struggles and hardship, motherhood and caretaking was a road to discovering more about herself.

Ever since I can remember, my mother has told me stories of her mother, Bhiji, who died at the tender age of 50, eight short years after migrating to London from the Punjab. My mother took to saying that “Bhiji died of a broken heart”. Though a very talented seamstress who played several musical instruments and practised homeopathy, like many women of her generation, Bhiji’s was not an easy or happy life. Her own mother died in childbirth and Bhiji was “married off” to my Papaji when she was still young. Papaji’s family was less than welcoming of her, often reminding her that she was an orphan and treating her like an outsider. Bhiji ultimately became mother to five children though it’s possible she successfully aborted several others. Her memory can vary on this, but my mother has said more than a few times that Bhiji tried to no avail to abort her. She is supposed to have apparently thrown herself down stairs, sat in steaming hot water until she could barely stand it and eaten foods that were known to trigger miscarriages. This would have been in 1949, just two years after the Partition of India which forced my family to leave their ancestral home in West Punjab for East Punjab.

It was Bhiji who I saw in my mind’s eye when I miscarried. It was as if she was with me, in spirit, to reassure me that I was not wrong for wanting this to happen.

Though my mother remembers Bhiji as a deeply loving and committed mother, it’s hard not to wonder what Bhiji would have done with her life if her life had not already been decided for her, if she lived in a place and time that respected her personhood and supported her in more meaningful ways. I can’t say I know because I don’t think that even in 2016 we live there yet.

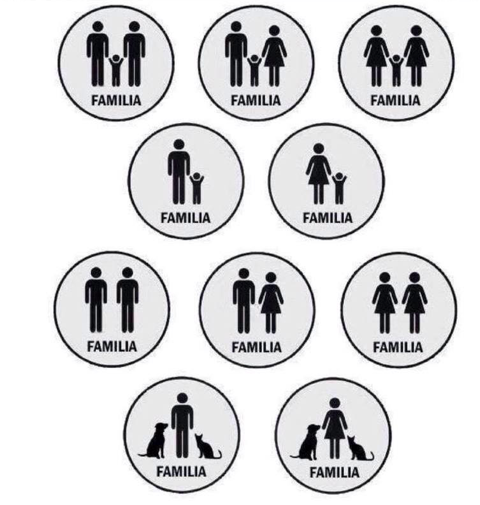

Here: three generations of women with three distinct attitudes to motherhood. Because womanhood is not a uniform experience and it doesn’t necessarily involve a calling towards childbirth.

There are as many reasons why women don’t have kids as there are for why they do. But that the latter is normalised while the former is ‘otherised’, shamed and rendered suspect is a flattening of womanhood. It is the shoving of womanhood and, by virtue, all women into horribly tight spaces, denying us recognition of the full expression of our creative offerings.

At the same time, for all our veneration of motherhood, we do an awful job of honouring mothers. We systemically fail them by short-changing them, denying them material support and meaningful recognition and making a space for them at the highest levels of decision-making. And so we must collectively rethink our attitudes around motherhood and womanhood, checking any tendency to conflate the two but also going beyond semantics to honouring all women and, in turn, raising the consciousness of humanity. This need not just be the role of mothers. In this sense, we are all mothers because we all have the duty to uplift humankind.

“’Cause I’m a woman

Phenomenally.

Phenomenal woman,

That’s me.”

– Maya Angelou, Phenomenal Woman

Cover image from Twitter