Stories of lost homes can be found in every corner of the world today, and yet people tend to cover them up, fear them, or put them away for another time so they can build the life they have dreamt of for themselves and their children. But these stories carry immense value – for us as well as our future generations. Stories can be therapeutic. They connect us to each other, make us feel more human, less alone.

Kitna khauf hota hai

Shaam ke andheron mein,

Pooch un parindon se

Jin kay ghar nahi hotay

How much fear one feels in the dark,

Go ask those birds who do not own a house.

– Mirza Ghalib

My engagement with lost homes and homelands began the day I was born into a family of survivors of the Partition (of the British Empire that led to the creation of India and Pakistan in 1947). That feeling of loss continued to cling on to me well into adulthood, and seeped into my academic and professional pursuits. Empathy for lives shaped by loss brought me to the world of storytelling. Last year, I helped create a beautiful documentary film about the lives of people affected by the Partition. We interviewed a lot of people, mostly family and friends of family on both sides of the border. Somehow, the narratives of the women we interviewed stood out. Their pain seemed to be more personal, heartfelt and almost tangible, even after almost seven decades.

The following are excerpts from an interview I conducted with my grand-aunt, Jitender Sethi, during the production of A Thin Wall, a documentary film about personal narratives from the Partition. The anecdotes mentioned here have not been featured in the film.

My grand-aunt was sixteen years old in 1947. She belonged to a Sikh family, and her father was an employee of the Railways. They moved to a new city every two years, and in 1947, they happened to be staying in the Railway colony at Wazirabad, 400 kms north of Lahore in what is now Pakistan.

Jitender remembers a very safe and happy upbringing with an active social and family life, even till about ten days before the Partition. She explains, “Railway colonies are always away from the cities. We were a huge colony with all Railway employees, right from the linesmen to the senior officers. And these colonies are always on the opposite side of the city. You had to cross the railway line every time to go to the city.

“Being in the Railways, we had our own club, we had our own games. We were busy just with the whole crowd of the colony. We never mixed so much with the city people because we were far away from them. Our only relationship with the city was to buy our rations (groceries) and other things, plus go to colleges and schools which, naturally, were also in the city.”

There was easy intermingling between Hindus, Sikhs, Muslims and Christians in the Railway colony. Jitender says, “There was no question of having any religious bias. We used to be friends with everybody. Actually, most of our friends were Muslim. I was studying in a school where the language was Urdu. I didn’t even know Hindi because that was not taught there. Very few schools had Hindi. It was just Urdu because it was connected to the north of Punjab.”

Somehow, every school Jitender went to had only two languages to offer: English and Urdu. She was very comfortable with reading, writing and speaking in Urdu and continued to use the language later even in Delhi where she completed her studies as a refugee.

Jitender goes on, “We would go and watch films in the theatre. The Muslim women would be in purdah, so they had a special place designated for them. We would also be sitting with them in there. There were both Hindu and Muslim girls, so there was nobody to say, not even parents, that you should not mix with or talk to anybody in particular. In our day-to-day routine, we had Muslim friends and Hindu friends, and Sikhs too. We would all go for outings together.

“When rumours of the Partition spread, many families began leaving their homes and moving out. How the Hindus and Sikhs behaved there (in what was to be India), Muslims did the same things here (in what was to be Pakistan). They would say, ‘Let’s go loot!’ Whatever they would find in these empty homes, they would bring it back and distribute amongst themselves. They took everything of value – money, clothes, etc. – and threw the books away.

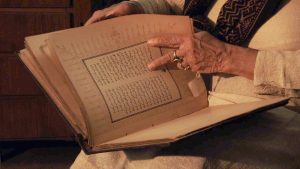

“When I was walking there in the evening, books were lying in the drain. I wondered where they came from. The security guard said that the people who did the looting had been standing there going through the loot, dividing it amongst themselves – and they threw all the books away. There were many that were in a bad shape, but there was one I brought back with me. It was a book of poetry by Ghalib. Who knew whom the book belonged to? Who could I have given it to? And I was very fond of Ghalib. I picked it up because I thought, ‘Who will care for a book?’ And I still have it.”

Who will care for a book as the world around you falls apart and the ground below your feet brutally cracks into separate nations? Jitender has had the book of Ghalib’s poetry with her for seventy years now. After a little bit of searching, she found it kept safely locked away in a closed bookshelf, and I had the privilege of holding it in my hands.

Once Jitender moved with her family to the newly independent India, a new chapter began – the chapter of life as a refugee, with a language and culture that was not her own. Jitender says, “I went to Ludhiana (in the Indian state of Punjab), then Saharanpur (in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh), and then we moved to Delhi. I came to Delhi for my Bachelor’s degree, so I was staying with my father’s friends in Delhi.

“Once you’re in college, you make new friends, but that closeness never happened. That is actually a very sad part of my life because by that age, you have made your friends. You have been with them for years together. Even if we were moving with my father’s job in the Railways, we would get re-posted to the same place and meet those friends again. But after coming here, life changed. The college I joined had a special second shift that had been started for refugee children. So everyone was a refugee.

“We didn’t miss much when we moved. Mainly it was that the life there was very different. Here, we were in the cities. Everywhere we went, we were to live in cities, so it was not easy to make friends. In addition, we couldn’t just go out, play, and come back. Here, everything was very regulated. Here, if your college had the facilities, you could do it. But over there, it was routine. Every evening you would get dressed and go to the club. Those clubs were not posh clubs like the ones you see nowadays. They were clubs for middle-class people, and those from the Services. There was a feeling of safety, and you felt like everyone was like you, so you could mix with the crowd, and have fun. That was totally missing here.”

The change was dramatic at first, and continued in more subtle and all-consuming ways to alter daily life. During the rioting before and after the Partition, on both sides of the border the fear for the safety of women had come to mean protecting the ‘honour’ of one’s family and consequently that of the larger community. This fear continued even in their lives as refugees in their new homes.

“After all that had happened, parents became very strict. They were not able to let go. They would say, ‘Don’t meet those people, who knows who they are’. There was a time when they wouldn’t even ask who I was talking to. All of a sudden, everything became suspicious. They would say, ‘Who knows what kind of people they are – don’t talk to them, don’t call them over, don’t go to their home’… all that happened. Life had changed completely.”

While reflecting on the late 1940s, Jitender, along with the other women I interviewed for the film, spoke not only of grief, but also hope. It seemed like they were collectively narrating a universal story of survival against all odds. I sat in amazement looking at the strength of these women who had rebuilt their lives and lived to tell the tale.

Cover image of a younger Jitender Sethi courtesy of the author

हिंदी में इस लेख को पढ़ने के लिए, कृपया यहां क्लिक करें।