SCENE 1: THE AUDIENCE

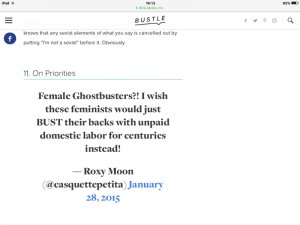

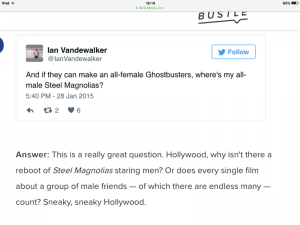

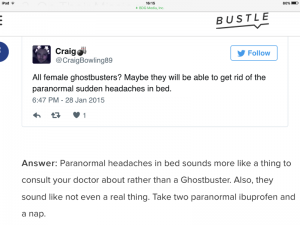

These are screenshots from a 2015 article titled 12 Sexist Reactions To ‘Ghostbusters’ All-Female Casting & Thoughtful Responses To Put Each Concern To Rest, where the writer, Kadeen Griffiths, has shot back at a random selection of audience Tweets about the remake of the film Ghostbusters with an all-female lead. These reactions from audience members represent an almost phobic, fear-filled discrimination against actors based on their sex and gender identity, even in a film that is a comedy about exorcising ghosts! Nah. Comedy. Exorcising ghosts. Women can’t do that.

Sexism such as this dominates the emotional and intellectual landscape within which we grapple with issues of sexuality. Sexuality and sexual expression are fettered by what the sexist thinks they should be.

So what is it that women can do?

Tamil film director G Suraj (also known as Suraaj) was quoted as having said, “Basically, we are a bit of a low-class audience. The audience pays money to watch the hero do a fight and to see the heroine in glamorous avatar. I’m not a big fan of the heroine wearing a full saree; if we’re paying good money to watch a film, we should expect Tamannaah (a popular female actor) to be completely glamorous. If you’re expecting a movie dedicated to art, then that’s something else altogether; a commercial movie should have glamour … because the heroines who have made it big today are the ones who have done these glamorous roles. Boys should enjoy the film in the end, that’s what I say.”

There are a number of different ways to approach this theme, Films and Sexuality. One way is through the eyes of the popcorn-eating, samosa-chomping, money-paying audience member who chooses to see or not see a film, who likes or dislikes it, who makes the film a box-office hit, or pans it.

Is there a difference between the male gaze, the boys who should enjoy Suraaj’s film, and others? Between gazes that may or may not identify as male, female, or any of the numerous possible variations of sexual and gender identity?

A sampling of audience reviews of the 2016 Bollywood film Force 2 yields interesting things to think about. Assuming gender only on the basis of the names of the reviewers, a female reviewer shows enormous appreciation of the ‘action’ capabilities of the female lead. She Tweets, “We’ve always loved John in action, but watch out! @sonakshisinha is the new ‘action hero’ in town. You go, girl!’ On the flip side, another reviewer, most likely male, has this to say:“#Force2 is @TheJohnAbraham show all the way. His sculpted body, washboard abs, vein revealing biceps have been strategically portrayed 🙂 Like the way the movie breezes away in the 1st half only to become little slow post interval & end quite predictably towards the end #Force2 Sonakshi is clearly overshadowed by the gutsy, “throw caution to the winds” John! She must try and avoid playing a feminist:)”.

One of two characters in a comic strip discussing whether or not to see a film came up with a rule that could begin to approach some of these issues. Here’s the rule:

(1) A film must have atleast two female characters who

(2) talk to each other, about

(3) something other than a man.

This is the Bechdel Test. Alison Bechdel in her comic Dykes to Watch Out For came out with this rule in a 1985 strip. That’s over thirty years ago.

SCENE 2: THE INDUSTRY

As reported in an online article in The Guardian in 2013, Swedish cinemas decided to try and apply the Bechdel Test to films to give them ratings. Quoted in the article, Ellen Tejle, director of Bio Rio, (an art-house cinema in Stockholm), says, “The entire Lord of the Rings trilogy, all Star Wars movies, The Social Network, Pulp Fiction and all but one of the Harry Potter movies fail this test”. A study mentioned in the same piece reveals that a ratio of two is to one of male to female characters in movies hasn’t changed in six decades: “That study, which examined 855 top box-office films from 1950-2006, showed female characters were twice as likely to be seen in explicit sexual scenes as males, while male characters were more likely to be seen as violent.”

Approaches to sexuality, attitudes towards female actors, dictated by pandering to a stereotypical male gaze, are coming under increasing scrutiny from diverse audiences. Returning to Suraaj, he is in trouble over the sexist comments he has made in his interview on a YouTube channel about female actors. Tamannaah, who starred in his recent Tamil film Kaththi Sandai has responded on Twitter:

In 2015, during the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival in India, well-known actor ShabaniAzmi, speaking as part of a five-member panel of women from the film industry, made some hard-hitting observations about Indian cinema, particularly Bollywood ‘item’ or song-and-dance, numbers: “The interesting thing about item numbers is that the actors who take part in it claim that if a male actor can expose his behind then why can’t she expose her cleavage, which is like commodifying yourself. In actuality, you are surrendering to the male gaze, because the business of cinema is the business of images. So when you have a woman with a heaving bosom, a shaking navel, and a swivelling hip, in fragmented images, you are robbing her of all autonomy and subjecting her to the male gaze and now, that is not a celebration of sensuality.”

Take a look at Angry Indian Goddesses (2015). A film with seven female characters comprising a group of friends, a story that explores the stereotype in the lives of some of the women and breaks stereotypes through the lives of the others. A reviewer praises the effort of the film, filmmakers, and actors, despite ‘errors’ in the film.“Are we really seeing seven female Indian human beings on the big screen, hanging out together, talking, doubling up with laughter, fighting, crying, partying, sharing secrets and forming new equations? This is that rare Indian film featuring a group of real women – women who could be you and me – bonding, responding to what life throws at them and living.” It is a path-breaker.

Yet, many factors specific to the Indian situation have influenced the way the film has depicted these characters, in particular, the lesbian characters. As this reviewer points out, due to past conflagrations catalysed by the religious profile of characters in the 1998 film Fire that had sexuality and the lesbian relationship at the centre of the story, Angry Indian Goddesses looked for a safer route home. The journey wasn’t easy. In an interview, the film’s director Pan Nalin has spoken of the huge challenge of financing this film, with Bollywood studios refusing to even meet the team. “We then tried private investors, that didn’t work. Or they would say, at least put one male star in the film. That was the argument.”

In an article titled Women in Slasher Films: How Sexism Shapes a Nation, the author has pointed out how murder scenes in films linger on in detail when the person being murdered is female. The violence done to a female character takes up more screen time than the violence done to a male character. “The killers in these films seek to re-establish male dominance and to punish sexually active women. The killers never explain their fury and their misogyny. The popularity of slasher films shows that we still live in a rape culture society that despises female sexuality and liberation.”

SCENE 3: THE CRITIC

Here is how a well-known male film critic, Rex Reed, criticised the 2013 film Identity Thief, a film in which Melissa McCarthy plays the female lead:“Melissa McCarthy (Bridesmaids) is a gimmick comedian who has devoted her short career to being obese and obnoxious with equal success. Poor Jason Bateman. How did an actor so charming, talented, attractive and versatile get stuck in so much dreck?” He also calls her a “female hippo”, “cacophonous”, “humongous” and “tractor-sized”. His sexist outburst in the guise of film review has come in for much-needed criticism.

Questioning the role of criticism and the critic also leads to its own, somewhat dubious, treasures. A 2013 study entitled Gender @ the Movies: On-Line Film Critics and Criticism tracked over 2,000 reviews by 145 writers on the film review site Rotten Tomatoes. The tracking was over a two-month period. Findings include:

- “Top male critics wrote 82% and top female critics 18% of the film reviews featured on the film review aggregator site.”

- “78% of the top critics writing in Spring 2013 were male, 22% were female.”

The study didn’t attempt age disaggregation, but there is evidence to show that age buys into prevailing attitudes and this perpetuates sexist behaviours. Actress and comedian Amy Schumer met a 17-year-old film critic at an event. He later Tweeted, “Spent the night with @amyschumer. Certainly not the first guy to write that.” Amy’s response:

He apologised to her later. The episode will leave him with something to remember for a while.

In a 2013 New York Film Academy film school blog, there’s an infographic depicting key aspects of the portrayal of women in the Top 500 films of 2007 to 2012. Among other nuggets, the information presented includes:

30.8% of speaking characters are women.

28.8% of women wore sexually revealing clothes as opposed to 7% of men.

26.2% of women actors get partially naked while 9.4% of men do.

77% of Oscar voters are male.

Does this impact the relationship between films and the sexuality of the human beings who watch those films? Most films primarily cater to a single category of gaze, and the sexuality of that gazer: male and heterosexual. Audiences and actors, filmmakers, and critics, it’s time to explore the diversity of gaze. For the joy of it, the truth of it, and the need for it.

Cover image: Movie still from Kaththi Sandai