When the editors of In Plainspeak first approached me with the idea of self-care and sexuality used in conjunction, I drew a blank. Care had connotations of method, deliberation, caution, whereas the sexual seemed in the realm of impulse and expression, of pleasures sought and given spontaneously. But what architecture of considered actions could one fashion for oneself in pursuit of sexual flowering, I thought. Is it not a liberal conceit of sorts to imagine that having undertaken these, one then faces the world a more sex-positive, self-(and therefore other) affirming individual, a better conduit of pleasure and union? (The worthiness of these pursuits, and the historical and cultural loading in that worth, is another discussion altogether). Over the course of thinking, talking, and writing this piece, my initial misgivings have eased, somewhat.

It is a truism that sexual pleasure, while uninhibited in the immediacy of experience, is also deeply socially structured. Sex is political. Shame and guilt police the boundaries of our sexual lives. The shame imposed on the ‘slut’, the ‘pervert’, the ‘whore’, the ‘homosexual’, to name a familiar few. Some of us pay a heavy price when we push (or find ourselves pushing) these boundaries. Having painfully navigated and crossed these peripheries, we emerge only to find ourselves facing other forms of close combat. Where shame doesn’t kill us or reduce us, there is always, reliably, the family, neighbours, landlords, employers, the village or the state to try us and punish us, even stone and kill us, depending on which part of the world we find ourselves in. This is a problem.

Some psychoanalytic literature locates the origin of sexual shame in the incest (and homosexual) taboo that marks our early childhood relationships with our parents. If these love and care relationships become the prototypes informing our adult intimacies, then the shame and shying away that our parents experience around their sexual bodies and desires, especially but not exclusively in relation to ours, will also mark our adult love relationships. Fathers who once embraced their daughters with abandon but who now shy away from these bodies newly in sexual bloom inadvertently condition the shame in some forms of heterosex. Seeded here is also perhaps the basis of passion in the new or the novel, and its sad divorce from the familiar and the known. “No, I don’t fuck friends.” “Lovers can’t be friends. Your wife could be your friend, but not your lover”.

We do not need to buy into psychoanalytic theory to accept the ways in which our relationship to our bodies and to its possibilities are deeply conditioned by these powerful early models in our lives. Those chhee–chhees around most bodily experiences such as pooing and peeing (and when older, bleeding periodically), the exaggerated, mock chastisement for the accidental underwear-flash or nudity, all of these condition shame. Think of the little-one walking in wide-eyed on guests, minus undies, little willy waving. My friend recounts how, growing up, there was one object around which cohered much intrigue and darkness and which, when brought to light and consciousness through accident, (usually) provoked much commotion and outpour of disgust, fear and outrage: her (used) panties. She notes how her brother’s jocks seemed not to be so much invested in explosive meaning. They seemed to enjoy freedom of movement in their family, spatially and otherwise.

The deliberation in care (at odds with the spontaneity of desire) and the routine in it (at odds with the freshness of passion) are not the only fraught, if fruitful, contradictions in the conjunction of care and sexuality. Care also typically signifies other-orientation, self-annihilation. A routine concern for the (bodily) needs of the young other as we spoke of, but also the aged other, the sick other. Care here is something that attaches easily with what may be called feminine functions.

Indeed, in sex, certainly in heterosex, but perhaps in some forms of homosex or queer sexualities as well, this self-annihilation associated with the feminine finds a common if not steadfast parallel in the feminine as object of the masculine subject of desire. Here, we have the much-problematised feminine love, desire and pleasure in waiting rather than pursuing, being looked at rather than looking, in self-sacrifice and service. (Someone reminds me that love and lust ultimately breaks these boundaries of the masculine and the feminine, the active and the passive, the dominant and the submissive, master and slave –a perfect dissolution in each other, a la Radha-Krishna in union.)

Care also associates specifically with the ‘good feminine’ functions, for the sexually active, desirable and seeking mother is the selfish mother: one of those anomalies that invite shame-inducing censure and punishment. And barring that, pride of place as MILF (Mothers I’d Like to Fuck) in porn portals, outside the charmed circle, the perimeter that marks off the acceptable and the respectable. Alternatively, the ‘slut’ (or the single woman) is denied motherhood; her independence, excess and proclivities for variety, risk and adventure, inadmissible crucibles for nurture.

Wide seem the experiential lands that induce shame, many the children ousted by the civilising, socialising missions and in need of care, and vast the potential for sexual self-care. Sexual self-care by this logic is a political act. And it becomes in part the work of sexual activism, of ‘experiential’ workshops, ‘theoretical’ courses on gender and sexuality (and Dan Savage), and magazine series such as this one, to aid and encourage it. Touched by the magic wand of (self-)knowledge, the hope is that we are thereby catalysed into a process that, whether willed or outside our will, reorders our relations with our bodies, our selves, our worlds.

Thank you, Bhupinder Tomar, Bindu Kay Cee, other friends and my many lovely students for the many fabulous conversations around this theme.

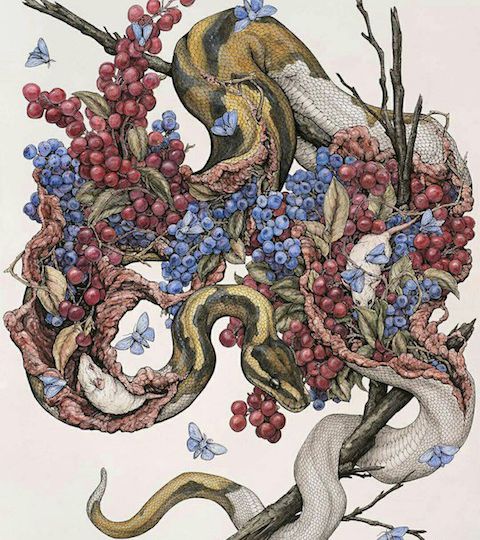

Cover image courtesy of Lauren Marx

हिंदी में इस लेख को पढ़ने के लिए, कृपया यहां क्लिक करें