Two recent experiences provide an excellent lead in to the issue of Accessibility and Sexuality.

Overheard last week in a classroom, a staff person tells the children in the context of describing themselves, that they must choose either to be heroes or heroines, can’t be both. Students include some with visible, others with less visible or with invisible disability. No question of anything apart from the male-female gender binary, certainly not. Average age of these students, perhaps 12 to 14 years.

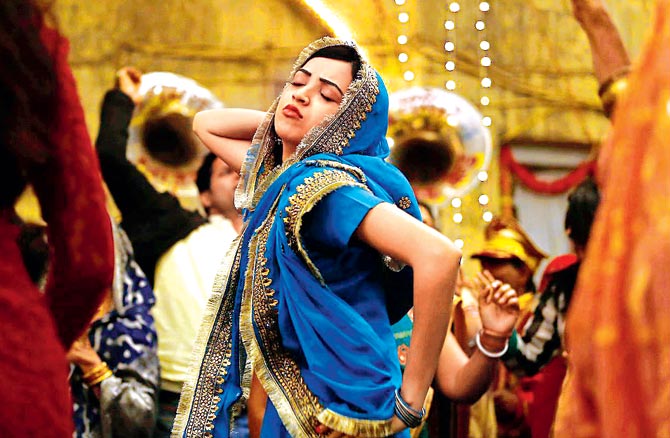

On Facebook, there has been much discussion about the film, ‘Lipstick Under My Burkha’. In an article on audience reactions to the sexuality of an older woman as depicted in the film, the writer says, “though we’re all for encouraging female-centric movies and will call out Pahlaj Nihalani for denying Lipstick Under My Burkha its due certification but when watching the film in a theatre, and a posh Mumbai one at that, we’ll giggle and mock Ratna Pathak Shah’s character in the movie and take cheap thrills in Konkona Sen Sharma’s character suffering from marital rape.” The writer then proceeds to share the content of Tweets sent out by a journalist watching the film who describes the experience of sitting with an audience where “Ratna Pathak’s beautiful portrayal of a 50+ widow who reads Hindi equivalent of ‘Mills and Boon’ and has desires evoked responses like “budhiya ko dekho, jawaani chaa gayi hai”, “budhiya abb swimsuit pehnegi” … Budhiya this and Budhiya that. “Budhiya” has no right to be human. “Budhiya” can’t have feelings.” (For non-Hindi readers, ‘Budhiya’ is a pejorative way of referring to an older woman. The responses were along the lines of saying, “Look at that oldie, she has illusions of youth”, and “Now the oldie will wear a swimsuit.”)

There is much to analyse in these two experiences and all of it brings together issues of Accessibility and Sexuality. What are the assumptions made about sexuality, how do these relate to age, ability, and disability, when and where do issues of accessibility become pertinent, are there some populations to whom issues of accessibility matter more than to others, are all these issues the same for all, how does able-ism creep into our approach to these questions? Where do the boundaries between individual, family, school, public audience, society, law and administration and concepts of human rights and justice become porous, enabling or disabling the core fundamentals of a human being?

Access to concepts and ideas is crucial to issues of accessibility. It is not possible to access or demand access to something unknown and unarticulated. Access begins from birth, some people believe, even before birth. This includes access to concepts – such as the concept of access and accessibility, the concept of sexuality, of the gender binary, or that sexual desire and sexual pleasure cut across age and ability. From the first breath to the last, human beings are surrounded by concepts and ideas about sexuality, articulated or reflected in attitudes, approaches and practices that comprise the environment around them, at home, at school, in the playground, neighbourhood, cinema hall and marketplace. Quite often, the barriers to accessing concepts and ideas are also human beings who block concepts they are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with. Therefore those children in the classroom describing themselves have access to the concept of hero and heroine and a choice of either or, but all other concepts of gender identity remain out of reach, unless their school environment supports or encourages access to such.

A few key concepts provide entry points to this Issue In Focus and these include accessibility, ability, disability, ableism and sexuality. Each concept must be understood independently, before we identify the impact of the interconnections between them.

Too often, when we think of accessibility, we visualise wheelchair, ramp, toilet with hand rail, or we think of technology and the Internet, of screen readers, voice recognition software, Braille terminals and web accessibility. All of this is certainly a part of the experience of enabling or hindering access, to a place, a space, a service, or an experience, but by no means are these either the beginning or the final solution to the challenge of accessibility.

Accessibility is most often, most simply understood in the context of obvious or visible disability. Disability is defined by the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability thus – “Persons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others.” So, in the context of disability, Article 9 of the UNCRPD says: “To enable persons with disabilities to live independently and participate fully in all aspects of life, States Parties shall take appropriate measures to ensure to persons with disabilities access, on an equal basis with others, to the physical environment, to transportation, to information and communications, including information and communications technologies and systems, and to other facilities and services open or provided to the public, both in urban and in rural areas.”

The fact is that a disabling environment can throw up challenges of accessibility to many more populations. Accessibility is not pertinent to a particular population or three, it is pertinent to all. It is about access, or entry, or opportunity to experience, ideas, services and spaces, real and virtual, that exist for us all, without barriers that may be due to physical or intellectual impairment, or psychosocial disability, or societal attitudes, unjust legal restrictions, economic disadvantage, caste, class, race, gender, sexual identity, or a number of such factors that have historically contributed to marginalisation, injustice and the oppression of different populations. Thus, accessibility means different things in different contexts, but the common thread running through it all is the upholding of rights and the creation of a social, legal and political environment that is sensitive to the importance of access as a working reality in the lives of all people. This is why accessibility is about the architecture and construction of a building, just as much as it is about the architecture of a website or design of a phone app, the access to livelihood and employment opportunities, to justice systems, to housing and shelter, to companionship, relationships and sexual experiences and expression. It is also, fundamentally, about the concepts, ideas and information so freely available in some environments to some people, unavailable or inaccessible in those and other environments to many more people.

The concept of ableism emerges in this discussion because often sexuality is not seen as an issue in the lives of those deemed not-able or disabled, those who do not meet the dominant societal standard of body and mind. As defined on the website of Stop Ableism, “An ableist society is said to be one that treats non-disabled individuals as the standard of ‘normal living’, which results in public and private places and services, education, and social work that are built to serve ‘standard’ people, thereby inherently excluding those with various disabilities.”

Sexuality – another concept most often narrowly understood as confined to sex, is a broad concept that applies to our identities, about the way we feel about ourselves, dreams, desires, relationships, growth and evolution on what is sometimes a sliding scale far more real and layered than the gender binary. A generally accepted definition of sexuality as articulated by the WHO says, “Sexuality is a central aspect of being human throughout life and encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy and reproduction. Sexuality is experienced and expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, beliefs, attitudes, values, behaviours, practices, roles and relationships. While sexuality can include all of these dimensions, not all of them are always experienced or expressed. Sexuality is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, ethical, legal, historical, religious and spiritual factors.”

Accessibility and sexuality connect in a damaging way across lives, when we decide for an ‘other’ who they are, how they must be and what they must feel, particularly in sexual expression, relationships and identity, and we enable access only to those concepts, ideas, information, places, spaces, products and services that we think that ‘other’ should access. ‘We’ in this case standing for the dominant, as opposed to collective, voices of society, community, development, education, employment, health, enforcement and justice systems.

We take away the right to experience and express sexuality when we deny access to all of this, in concept and in experienced reality. Concepts include disabling myths and generalisations about the sexuality of older people, of younger people, of persons with physical impairments, intellectual disability, or psychosocial disability, of their desires and desirability. Experienced reality becomes a hideous translation of these concepts as we erect barriers, of which the lack of support is the foremost. This experienced reality linking accessibility and sexuality has been a strongly emerging theme in the updated version of TARSHI’s Working Paper on Sexuality and Disability in the Indian Context. Between 2010 when this paper was first published and now, new spaces, voices and efforts, and many changes, such as in the legal landscape of our country, have emerged. These voices and efforts prove that accessibility and sexuality connect in creative and positive ways when rights become the rallying point for advocates and self-advocates, families, friends and communities, for services providers, product designers and marketing teams. This is when architecture in the real world, comes together with architecture in the virtual world, pursuing an attitude and approach that acknowledges sexuality as essential to the experience of being human, throughout the course of a lifetime.

Accessibility begins with access, enabled or denied, to concepts and ideas. At the core, beyond the architecture of the real and virtual worlds, it is about the architecture of the ways in which this access is broadened, to not only accommodate, but to nurture, the myriad expressions of human minds and bodies.

Cover Image: A still from the movie Lipstick under my Burkha (2017)