Although patriarchy is deeply entrenched in modern-day India, the country has a long tradition of women who resisted conformity, even under severe societal pressure. These stories of feminism are as multicultural and diverse as India itself. Here is a look at the fascinating journey of feminism through the ages in India.

PHOTO SOURCE

In the literature of the early Vedic period, there are several mentions of female scholars like Lopamudra, Maitreyi and Gargi. Among the educated women of the era, Gargi Vachaknavi is believed to be a pioneer. In the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, she has been credited for having drawn forth from philosophers some of the most profound questions of Vedanta – the nature of the Soul (Brahman) and the origins of the universe – during a public debate with Vedic philosopher Yajnavalkya.

In a court filled with male philosophers, Gargi fired question after question at the great sage, stumping a man who had never before been left at a loss for words. At one point, Yajnavalkya even warned Gargi that her head would fall off if she continued but when others failed to elicit the answer she was clearly aiming for, she continued her bold questioning. As Brian Black writes in his book, The Character of the Self in Ancient India,”Gargi was, in fact, Yajnavalkya’s strongest opponent, stronger than even her male counterparts.”

Years later, Queen Didda, who had a leg disability, ruled Kashmir with an iron hand for more than four decades during the 10th century. Her tremendous political survival skills, her ability to rule and her achievement of stability in the fractious kingdom she had inherited is why she is sometimes called the Catherine of Kashmir, referring to the ruthless Catherine the Great (the longest ruling female leader of Russia).

In the 17th century, Bibi Dalair Kaur, a Sikh woman, formed an all-woman army to fight Mughal forces.

PHOTO SOURCE

When taunted by Mughal commander Wajir Khan about the weakness of women in the battlefield, she is believed to have replied fiercely with the following words:

“We are the hunters, not the hunted. Come forward and find out for yourself!”

Rani Velu Nachiyar of Sivaganga ruled her kingdom for over a decade, led her kingdom’s army in numerous battles and even formed a special women’s army named Udaiyaal after her daughter.

After succeeding her father to the Kakatiya Throne at the age of 14, Rani Rudrama Devi led several battles against the nobles in her kingdom who opposed her rule because of her gender.

PHOTO SOURCE

Rani Chenamma of Kittur, a princely state in Karnataka, was the first Indian female ruler to lead an armed rebellion against the British East India Company. In Maratha history, Tarabai of Kolhapur, Anubai of Ichalkaranji and Rani Lakshmibai of Jhansi are well known for their skill, efficiency, diplomacy, and bravery in fighting against their rivals.

During the 19th century, the Indian woman’s quest for civil, political and religious rights arose from the belly of the great social and religious reform movements of the era. Historians refer to the abolition of Sati as the first watershed moment in India’s modern feminist movement.

A lot of the early struggle saw educated middle class men such as Raja Ram Mohan Roy (who crusaded against social evils like Sati, polygamy and child marriage), Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar (who championed the cause of widow remarriage) and DD Karve ( who worked towards eradicating the bias against widows) take a feminist stand. Mahadev Govind Ranade founded the Widow Marriage Association in 1861 while Behram Malabari launched a campaign against child marriage and demanded legislature to prevent it.

PHOTO SOURCE: RAJA RAMMOHAN ROY, ISHWAR CHANDRA VIDYASAGAR, D D KARVE

During this time Indian women also continued to challenge the status quo in the background, struggling for their place in the sun. Some of the women who went on to become feminist ideals include Anandibai Joshi – the first Indian woman to study abroad, Kamini Roy – who spearheaded India’s suffragist movement and fought for a woman’s right to education, Kadambini Ganguly – the first woman to study Western medicine and, one of India’s first two women graduates, Muthulakshmi Reddy – who studied in a men’s college to become a doctor and went on to abolish the devadasi system. Others included Pandita Ramabai – who started a centre to support widows and studied the Kindergarten method of education, Rukmabai – who defied her child marriage to become India’s first practising lady doctor and Cornelia Sorabjee – the first Indian woman lawyer.

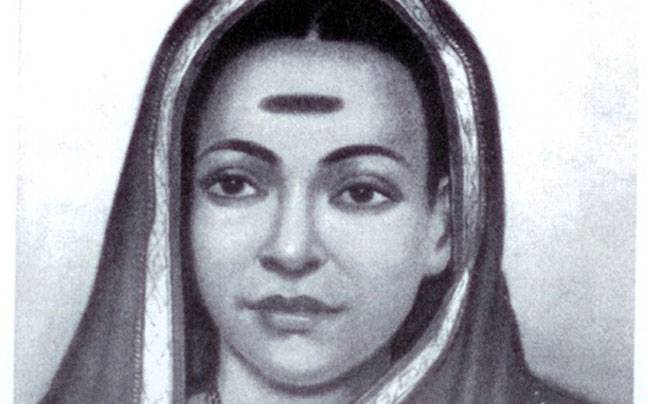

A special mention must be made of the inspiring woman who is often described as one of the first modern Indian feminists. At a time when people hardly acknowledged the grievances of women in India, Savitribai Phule, along with her husband Jyotirao Phule, fought injustices against women with all they had.

PHOTO SOURCE

In those days, widows used to shave their heads, wear a simple white sari and live a life of austerity. It was Savitribai who decided to stand up against this practice and organized a strike against the barbers in order to persuade them to stop shaving the heads of the widows, most of whom were still children.

She also noticed the plight of sexually exploited women who, after becoming pregnant, either committed suicide or killed the newborn due to fear of banishment by society. To cater to such women, she opened a care centre (called Balhatya Pratibandhak Griha or Infanticide Prohibition House) for pregnant rape victims and helped deliver their children. She also founded the first school for women at Bhide Wada in Pune in 1848.

The early 20th century too saw the rise of many courageous and strong-willed women who were instrumental in India’s freedom struggle. The stories of these women revolutionaries, trade union activists, and nationalists have long been an unsung part of the historical legacy that independent India inherited.

A little known story is that of Rabindranath Tagore’s sister, Swarnakumari Devi. A committed social worker, Swarnakumari started an initiative, Sakhi Samiti, in 1896, to help widows, orphan girls and poverty stricken women of Bengal. She also played an active role in the Indian nationalist movement. Her daughter, Sarala Devi, also grew up to be an independent and confident woman who believed in following her convictions.

PHOTO SOURCE: SWARNAKUMARI DEVI, SARALA DEVI

An accomplished musician and poetess, Sarala Devi completed her education at Calcutta University and challenged the social conventions of her time by taking up a job in a school in Mysore at the age of 23. After she returned to Bengal, she actively participated in the militant nationalist movement of the state. She also attended meetings of societies that had all male members and presided over boxing, judo, swordplay and wrestling matches organised by her.

The era also saw the rise of many women’s organizations like the All India Women’s Conference (AIWC). Women within the national movement had begun insisting on greater political and economic participation. These pioneering organizations included the Bharat Stri Mandal in Calcutta, formed in 1910 by Sarala Devi, and the Women’s India Association founded in 1917 by Annie Besant, Dorothy Jinarajadasa, Malati Patwardhan, Ammu Swaminathan, Mrs Dadabhoy, and Mrs Ambujammal.

Annie Besant also led the Home Rule League and was elected President of the Calcutta Congress session in 1917. The year 1917 was also significant as Sarojini Naidu led a delegation of women to meet the Montagu-Chelmsford Committee to demand a series of reforms in the condition of Indian women. In 1925, Sarojini Naidu was elected President of Indian National Congress, the first Indian woman to hold that post.

It is easy to dismiss some of these achievements by pointing out that most of these women came from affluent, educated and urban households. But even within their spheres, they all fought uphill battles to establish themselves as different and to speak out against the norm.

Post Independence, the question of women’s rights appeared to retreat from public discourse for a few years. The second wave of the women’s rights movement began in the mid 1970s. The issues raised this time were wide ranging – from land rights and political representation to divorce laws and child custody to sexual harassment at work, dowry and rape. The women’s movement interrogated the existing laws, with their questions becoming central in public discourse.

Indian feminist writings, especially those by Toru Dutt, Lalithambika Antharajanam, Ismat Chugtai, and Mahashweta Devi, also made their presence felt globally.

PHOTO SOURCE: ISHMAT CHUGTAI, TORU DUTT

In 1974, the Committee on Status of Women presented its findings in the form of a watershed report Towards Equality that laid the foundation of women’s movement in independent India, highlighting discriminatory socio-cultural practices, political and economic processes. Its authors included Vina Mazumdar and Lotika Sarkar, the duo who later founded the Centre for Women’s Development Studies in Delhi.

In 1980, an anti-rape campaign was launched that led to emergence of autonomous women’s organisation in several cities of India. There was Saheli in Delhi, Vimochana in Bengaluru, and Forum Against Oppression of Women in Mumbai among others. Special Interest Groups that focused on legal aid for women also came into existence and several legal reforms took place. A great example is that of the landmark Vishaka Guidelines that came into being in 1997, outlining the process for dealing with sexual harassment at the workplace (later superseded by the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act of 2013).

Entering the 21st century, Indian feminism engaged with a whole host of issues – from domestic violence and rape to victim shaming and consent. Indira Jaisingh’s tireless work was instrumental in the framing of the Domestic Violence Act (2005). Jaisingh was also the first woman to be appointed as an Additional Solicitor General of India in 2009. Senior advocate at the Supreme Court of India, Meenakshi Arora’s persistent efforts led to the framing of the Vishakha Guidelines, which later culminated in the legislation of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act (2013).

Photo Source: Meenakshi Arora, Vrinda Grover, Indira Jaisingh

Activist Kavita Krishnan set in motion a series of protests and uproar after the 2012 Nirbhaya rape case, which eventually led to the legislation of the Criminal Law Amendment 2013 that made changes in the existing rape laws in the nation. Identified by TIME magazine as one of the 100 most influential women in 2013, lawyer Vrinda Grover was also influential in the drafting of the Criminal Law Amendment of 2013.

Even though there still remains a lot of work to be done, the movement to secure rights for women in India has come a long way thanks to these inspiring and fierce personalities who made it possible by relentlessly fighting the forces of patriarchy. There were and still are many other individuals and organizations who are also working for gender equality and justice in India and their efforts are paying off.

Feminism in present-day India has been showing some encouraging trends. First, increasing economic liberty is allowing women to fight stereotyping. Second, what women want is changing – from economic rights to social and sexual rights. Third, women are not vacating their spaces – they are negotiating harder to expand them. Fourth, there is genuine partnership and collaboration among men and women, particularly youngsters, to embrace meaningful gender equality. Finally, the internet and information revolution is helping women form communities and networks, giving them a bigger voice and tools to organize themselves, forge partnerships and demand their rights.

Most academics attribute the growth of feminism in India to western influence, disregarding the fact that feminism is multicultural – the needs and problems of women who live in different countries are dissimilar. However, Indians did not have to borrow feminism from the West. Throughout history, Indian women have asserted themselves in multiple ways and broken free of oppressive social norms. These whispers of rebellion were bypassed or ignored by patriarchal documentations, but they were always there and they must be remembered.

This article was originally published here.