Friendship has always remained a thinly coded term for same-sex love within queer discourses, and early writings in favour of homosexuality frequently revisited this trope to historicise and naturalise same-sex desire. In this article I shall recount an interesting story of three friends – three eminent figures in the history of English modernist literature – whose life and art acquire intriguing meaning when read with an awareness of their sexuality, and how sexuality, besides their love for the arts, cemented an affective bond between them. This extraordinary friendship among the authors sealed through numerous adventures, escapades, misgivings, betrayals and heartbreaks of a ‘hidden’ sexual life, also underlines the idea of an emergent LGBTQ+ community, the possibility of forging a kinship beyond the biological family, without imitating the heteronormative models of partnership. This kinship might or might not be founded on erotic longing, but, was reinforced through emotional interdependence, companionship, and in sharing each other’s life, a life which could not be revealed to the world.

At the fin de siècle,a homosexual subculture was emerging in a significant way, especially in western and southern Europe. It was also the time when the homosexual Englishman was living in apprehension of the anti-sodomy law which had recently, by the example of Oscar Wilde, sent out a disquieting warning to all those who did not conform to heteronormative models of romance, desire and partnership. The neologism homosexual which Karl-Maria Kertbenyis credited with, had already acquired negative connotations, engendering the birth of a new species of anomalous humans; its binary opposite, heterosexual became the hallmark of normality against which any sexually deviant behaviour was judged. It was the time when sex, sexuality, conjugality and the human anatomy, in general, were of great interest to anthropologists, sexologists, philosophers, artists, psychologists and historians. While the likes of Edward Carpenter was relentlessly writing to defend the naturalness of homosexuality, counter-discourses to that were difficult to thwart. The last few decades of the nineteenth and the first few decades of the twentieth century were the most prolific periods of writing on sexuality, and today, it is well-known that several celebrated literary figures of the period were queer – some were fearlessly so, some concealed themselves behind straight masks for the fear of social and legal persecution. Among the latter group were the left wing poets, or the thirties poets, or the Auden group, as they were variously known as.

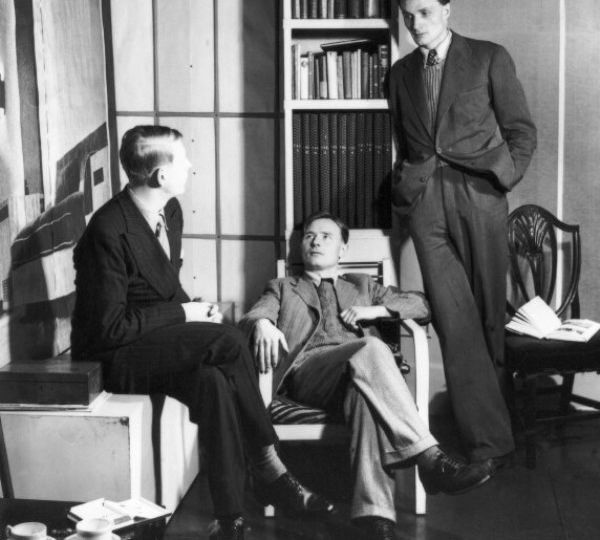

The thirties poets, namely, W. H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Stephen Spender, C. Day Lewis and Louis MacNeice, were deeply concerned with the worldwide economic depression, the Spanish Civil War, the rise of Fascism, and the beginnings of the Second World War. Evoking communism and the figure of the communist frequently, the thirties poets – not all of them – also often wrote on love, desire and longing. They were looked upon with suspicion for their homosexuality, although their sexuality was not quite a secret among close associates. Particularly, the three poets, Auden, Isherwood and Spender, had certainly forged a deep friendship beyond their artistic activities and political companionship. But, the ‘other side’ of this famed friendship was not revealed to the world for a long time. In fact, this interminably deferred ‘coming out’ underlines the unliveability of a sexually deviant life.

It was in Germany’s Weimar Republic that Auden, Isherwood and Spender found a new lease of life. No historical account of the Republic’s homophilic disposition could compete with the two fascinating novels – Christopher and his Kind (1976) and The Temple (1988) – two seriously deferred autobiographical accounts of Christopher Isherwood’s and Stephen Spender’s erotic lives and engagement with the politics of sexual identities during their stay in Germany in the first half of the twentieth century.It was in Germany that the three were introduced to alternative interpretations of Christianity, of the common placeness of homosexuality, and nuanced historical and scientific discourses surrounding it. Auden was friends with two anthropologists, Layard and Lane. He introduced them to a very young Isherwood, who was both appalled and fascinated by their radicalism and reinterpretation of God:

There is only one sin: disobedience of the inner law of our own nature. This disobedience is the fault of those who teach us, as children, to control God (our desires) instead of giving Him room to grow. The whole problem is to find out which is God and which is the Devil. And the one sure guide is that God appears always unreasonable, whereas the Devil appears to be noble and right. God appears unreasonable because He has been put in prison and driven wild. The Devil is conscious control, and is, therefore, reasonable and sane. (Isherwood 2)

This is only a little tip of the iceberg as regards to the massive revolution that was underway, only to be cut short by the rise of the Nazis in the late 1930s, in Germany’s Weimar Republic. A page from Spender’s (masquerading as Paul in The Temple) notebook written during his Berlin days, reads:

I feel as if a new life had begun here in Germany. I do not know precisely in what the newness consists, but perhaps the key to it is in these young Germans having a new attitude toward the body. Although I have never been puritanical in my outlook, I confess that till now, whatever I may have pretended to myself, I have always regarded my body as sinful, and my own physical being as something to be ashamed of…Now I am beginning to feel that I may soon come to regard my body as a source of joy. (Spender 54)

While radical challenge to puritanical Christian notions of the body, soul, God and Devil is more than apparent in the above two extracts, bodily pleasure, extricated from the realm of the sinful, was placed centre-stage, as evidenced by the Institutfür Sexual wissenschaft/Institute for Sexual Science, founded by Magnus Hirschfeld and Arthur Kronfeld in 1919 in Berlin’s Tiergarten Park. The institute was founded in the wake of the fall of the monarchy, and Germany’s coming of age as the most modern, democratic, welfare state of Europe. Hirschfeld, the homosexual Jewish sexologist, was widely well-known for his leadership of the homosexual emancipation group, Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee/Scientific-Humanitarian Committee co-founded with the Jewish doctorate in law, Kurt Hiller, in May 1897. Auden, Isherwood and Spender, all three, found a liberal environment, unthinkable in England, in which they produced some of their greatest works, while sharing with each other their sexual lives – particularly, their numerous affairs with Germany’s handsome working class men. The authors’ sympathies with working class struggles and deep faith in Marxist ideologies also, very curiously, reflected in their love life.

These writers belonged to a homosexual subculture within which literary works – consisting of representation of homosexuality, positive or negative, and original poems, short stories, novels, etc. – circulated amongst friends. In the Introduction to an anthology, Pages Passed from Hand to Hand: The Hidden Tradition of Homosexual Literature in English from 1748 to 1914 Mitchell and Leavitt write that ‘men who were sexually attracted to other men’ formed a “distinct and numerous reading class”, who belonged to a network which helped them ‘locate’ homosexuality in literature, which they ‘passed on to one another. Word of mouth dissemination: read this.’ (xiv; emphasis in the original). Several writers held back their explicitly ‘homosexual’ books for a long time, before they eventually ‘came out’ in print. E. M. Forster did not bring out Maurice, which was almost completed in 1914, but published only posthumously in 1971. Yet, Forster, who was well-acquainted with the homosexual subculture of England, is known to have risen in defence of Radclyff Hall’s path-breaking ‘lesbian’ novel, A Well of Loneliness in 1928, with several other male couples. But, surprisingly, not until his death, did people know about his homosexuality, not even his biographer, Lionel Trilling. Auden and Isherwood knew Forster well, who in turn was connected to Edward Carpenter, forming a subterranean queer kinship which was imbued with the thrill of preserving a secret.

Auden’s emotional connect with his non-normative fellow literary artists is seen in a plethora of poems dedicated to them – ‘The Novelist’ (dedicated to Isherwood), ‘Rimbaud’, and ‘A E Housman’, just to name a few. Although Auden did not write about their sexuality, these poems when read together today reveal a friendship which ran deeper than identifying with each other’s political ideologies or appreciating their artistic merits. Auden’s love poems, which are now read as ‘queer’, most of the time remained elusive about the gender of the beloved; but, they broke new grounds by imbuing an explicit eroticism which was uncommon in mainstream poetry. Auden was fiercely protective of his image of a revered poet, and did not want the world to know of his sexuality. Bozroth notes:

When Robert Duncan wrote him in 1945 to propose an essay on homoeroticism in his poetry, Auden asked him to refrain. When his most explicitly homosexual text, the pornographic poem “The Platonic Blow” (“A Day For a Lay”), was pirated in 1965 by the Fuck You Press, he disowned it. (4-5)

His agreeing to marry Thomas Mann’s lesbian daughter in order to help her escape to the United States; his raging love affair with Chester Kallman – were well-known in intimate circles. But, Auden did not agree to go public about his private life. Even Spender is known to have sued David Leavitt for portraying him as a gay man in While England Sleeps (a heavily edited version was published in 1993, following the lawsuit filed against it) and rewrote several lines in his poems in attempt to erase his gay past when he was knighted in 1983. This appears contradictory and unsettling given that Spender had been quite unequivocal about his sexuality earlier, and even later, particularly, when he chose to rewrite The Temple. Among them Isherwood was perhaps the most consistent in adhering to his sexuality publicly as underlined by his several novels, poems and letters.

The Temple was one of those novels which belonged to the culture of ‘pages passed from hand to hand’. Spender never published it for the fear of censorship and forgot about it, when a friend discovered a draft copy in an American university after decades. In the late 1920s, Spender had sent out typed out copies to Auden and Isherwood along with Geoffrey Faber, the publisher, who rejected it immediately on the account of its ‘libellious’ and ‘pornographic’ nature (Spender x). The novel, when revived, underwent several revisions, was eventually published in 1988, 60 years after it was actually conceived. The story revolving around, Paul (Spender), Simon (Auden), and William (Isherwood), dramatised ‘a happiness to be found in Wiemar Germany’ (Spender xi). In the introduction to the book, Spender underlines the intensity of the friendship between the three artists which enabled the emergence of a radical literature. Auden too acknowledges this friendship in The Orators, while Isherwood talks about it in his Christopher and his Kind. In this book, the writer looked back on his formative, youthful Berlin years, and filled up the gaps and elisions in his previous writings. Gore Vidal, while introducing the book, wrote, ‘Art and sex…intertwine in Isherwood’s memoirs’; but his earlier memoirs are fiercely ‘reticent’ about his sexuality, until in Christopher and his Kind, he chose to break the silence so much so that Vidal compared him, along with Auden, to Marlowe: ‘…each might have echoed Marlowe’s mighty line: I have found that those who do not like tobacco and boys are fools’ (xvii). Isherwood adapted an interesting narrative style in which he used the first person as well as the third person narrative, sharing with readers the deliberate elusiveness he resorted to in his earlier works – ‘These is a book called Lions and Shadows, published in 1938, which describes Christopher Isherwood’s life between ages seventeen and twenty-four. It is not truly autobiographical, however…The book I am going to write now will be as frank and factual as I can make it…’ (Isherwood 1). It was Auden who encouraged him to travel to Germany, where Spender soon followed him. The three, through their numerous sexual adventures, and literary activities, forged a lifelong friendship. Apart from the two books I discussed here, which now qualify as ‘classical’ queer literature, Auden and Isherwood have collaborated on several plays, such as, The Dog Beneath the Skin (1935), The Ascent of F6 (1936), and On the Frontier (1939). Auden, on the other hand, collaborated with his long time partner Kallman and the gay librettist Benjamin Britten in several operas. Discussing Isherwood’s relationship with his long term partner Bachardy, who he met later in the US, the Christopher Isherwood Foundation writes – ‘Their life with one another and with their countless friends became a kind of shared artistic project, and their relationship was to become a model for many gay men undertaking long term partnerships in the new openness of liberation. Its iconic status was enhanced by the double portrait of them which David Hockney painted in 1968’ (n.pag). However, much of these great works of art, produced through deep homoerotic or homoromantic friendship among great artists, rarely finds due acknowledgement as queer art. Such acknowledgement, some might contend, may not be necessary; for, art, as they say, has no gender (or sexuality). But, it can be argued that the queerness informing and underlining these works needs recognition for that would politicise these works infinitely, assisting the LGBTQ+ movement to a considerable extent, especially in nations such as India, where one celebrates Auden for his critique of fascism, but, shies away from him once his sexuality is revealed.

References

Bozroth, R. Auden’s Games of Knowledge: Poetry and the Meaning of Homosexuality. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Isherwood, Christopher. Christopher and his Kind.Introduction by Gore Vidal (1976).London: Vintage Books, 2012.

Mitchell, Mark and D. Leavitt. Pages Passed from Hand to Hand: The Hidden Tradition of Homosexual Literature in English from 1748 to 1914. London: Vintage, 1997.

Spender, Stephen. The Temple. Introduction by Stephen Spender (1987). New York: Grove Press, 1988.

The Christopher Isherwood Foundation. Accessed on 31 January 2018. < www.isherwoodfoundation.org/>