“Yes, I am Sudha, but why are you looking for me? Did I do anything wrong?” asked the old lady. She was sitting on a bench, reading a Hindi newspaper in the balcony of the old people’s home, an ashram run by the government. The sun was warm and comforting against her shoulder, almost creating a halo around her head. I introduced myself, told her where I am from and why I was there.

Rarely in life do we get the chance to reflect on our learning; the Leadership Program I’m currently pursuing is one where I have been fortunate to do so. As part of my field trip I am documenting ‘inspirational’ life stories, lived experiences of women from the lens of gender across age, class, caste, religion, and education in South East Asia. My field project titled ‘Amplified Voices – listening tour of inspirational life stories of women’ allows me to travel across Sri Lanka, India, Bhutan, and Thailand. I met Sudha Banerjee during my field trip in India in an old people’s home.

On learning about my prior experience of working in the field of mental health and human rights, she asked me if I knew how many types of hunger there were. I was obviously caught off guard. But as this was my second interaction with the residents of the home, I knew that conversations there didn’t necessarily begin directly. I told her that I didn’t know. She went on to explain that there are three: psychological hunger, physical hunger (for food), and hunger of the body. To keep the balance of the mind and body it is important to feed all three. She went on, “Do you know what or who is a characterless person? Not the one who sleeps with people. It’s the one who steals and cheats. But if anyone likes somebody and goes on to attend to the hunger of their body, it is called ‘sexual’, it’s very important and should be encouraged. However, one shouldn’t encourage live-in relationships, marriage is important to ensure that your sexual hunger is well taken care of.”

Sudha Banerjee spoke in Hindi and Bangla, and frequently used English words with perfect diction. She went on to say that there is no psychological peace when there is sexual hunger. I was surprised at how she was using such sophisticated rights-based language about mental health and illness that so many organizations are struggling to incorporate. She said, “I am speaking to you as a friend, not as a grand-daughter, or daughter. I speak clearly and honestly, hence people don’t like me that much.”

At this point I decided to address her as Sudha ji (ji is a term of respect), and not as Dadi (Grandma) a term that I had used affectionately with the other participants and that was much appreciated.

I didn’t need to ask further questions. She went on to share her story.

“My father was a Major in the Army. It’s because of this that I have lived in several states in India. I, born in a Maharashtrian Brahmin family, married to a Bengali Brahmin family and lived in Hyderabad for many years, so automatically speak Marathi, Bangla, Hindi, and Telegu. I understand Punjabi as well.”

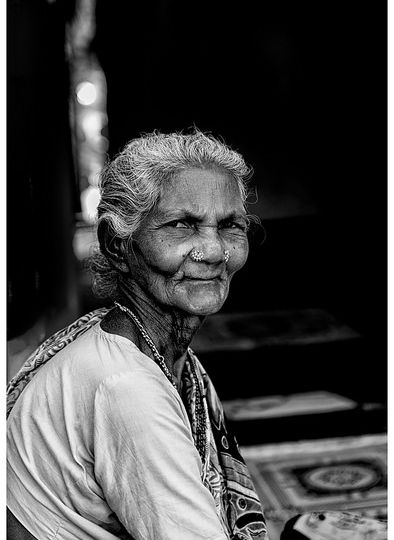

Sudha ji is fair, round, and wears thick glasses which makes her eyes look bigger than usual. She exudes pride and grace. This comes naturally to her, outshining her warm, sweet grandmother-like vibe.

“My family is from Jalgaon. We have huge mansions, ancestral land, and property. We were four brothers and three sisters, and I was my father’s darling. He would get me whatever I wanted, to the extent that if he ever forgot to bring something for me and saw my face fall, he would go back, rain or shine, to bring it for me. We belonged to the upper-most caste of Jalgaon and everyone knew us by name. All you would have to tell the rickshawala (driver of two- or three-wheeled transportation) was our family name, and you would be directly brought to our house from the station. My extended family was run by my Dadi (. She was a formidable woman, extremely smart, liberal, and educated. She studied till class VII and knew Ayurveda. She used to make medicines at home. She would tell us to go out, enjoy the garden, but to always do so in groups. We were never allowed to leave the house alone, or stand near the windows. Our mothers used to go in covered tongas (horse carriages) and watch theatre shows sitting behind the purdah (screen to keep women out of view). My grandfather was the District Collector. We followed all the rituals. There was a temple in our house, where people sang bhajans (devotional songs) from 3 to 5 in the afternoon. We were encouraged to sing during that time. I used to wear tailor-made fitted blouses and pleated skirts that went below my knees. After I got my period I used to wear the traditional blouse and ghagra (traditional long skirt) with a gajra (small flower garland) in my hair.”

Sudha ji spoke candidly, drawing threads from her fondest memories, weaving them into vivid images. She was a talking museum. She walked me through the lanes of her memory and life. I wasn’t using any recording device, or taking notes. I didn’t feel the need to. I could see her description and feel her emotions reflected in her magnified eyes.

“I was pursuing my Masters when I got married. My future mother-in-law saw me in my aunt’s house and asked for my hand. My father refused, saying that I was still studying. But my future husband, who was in the Air Force, had become adamant about marrying me. He even tried to kill himself. So my father relented and we got married. My husband was from a rich and propertied family. When I used to believe in God – now I don’t anymore – I used to pray that in my next life I would rather be an earthworm than have a husband like the one I had.”

Sudha ji looked too angry to continue. She paused, muttering something to herself, gathering her thoughts. I could sense she wasn’t ready to talk about her husband. And I did not intend on asking. She quickly switched the topic and asked me if I had ever heard of lesbians and homosexuals

I was a little taken aback again. I nodded vigorously, indicating a yes.

Pointing at a lady lying down she said, “Do you see that woman on that bed? She keeps looking at me. Which is why I wear this pallu (a part of the saree) on my head, to cover my face. But she is always looking at me shamelessly. You would think that we are old people, but you know when your hunger is not sated you always suffer. Which is why I feel that people should just get married to each other and live together happily. All the hungers should be taken care of properly.”

I asked her if in her life she had experienced a balanced consummation of all the hungers.

Sudha ji: “I have a daughter, so I have obviously been active at some point in my life… but it was not consensual. My husband forced himself on me.”

Me: “You didn’t want to have a child?”

S: “I did. Who doesn’t want to become a mother? But Ajay Banerjee (her husband) forced himself on me. He used to beat me up regularly. He was uneducated, a drunkard, a gambler, and would sleep with other women…”

Me: “What happened to your studies?”

S: “I wanted to continue my masters in Psychology but my husband wouldn’t allow me to go out of the house. He was extremely jealous about me. When I requested to, he said that if I go out of the house I will mingle with other men, they would see me and I could run away. Imagine how vile his thoughts were. Do you know that I got a job offer from All India Radio? There was a magazine called ‘Sunita’. I saw a job posting there, wrote my application in Hindi. Soon I received an offer letter, with a date and an appointment letter. Imagine my luck! I filled up the form accepting the offer and gave it to my husband to post it. But I never heard back from them.

A couple of weeks later, I found the letter in the pocket of his jacket. That afternoon when he came back for lunch, I asked him if he had actually posted my letter. To which he said that he definitely did. I took out the letter and showed it to him, and asked him directly why he didn’t post it. His only response was that he didn’t want other men to see me. You know how you try to project your thoughts on others…he thought others think exactly the way he thought. I was given three and a half kilograms of silverware, wrapped up in gold for my wedding. Ajay Banerjee would steal that from me. He used to regularly ask for money from my father. My father bought land for us in Tarakeshwar and we moved there. Ajay Banerjee was evil.”

Me: “Did you ever think of leaving him?”

S: “I did once. When my daughter was only two years old, I couldn’t stand it anymore and came to live with my father. My mother had already died. I stayed there for one and a half months.”

Sudha ji kept quiet for a while. She was probably collecting and organizing her thoughts. She got up and brought a small packet of butter cookies and a tiny bottle of water for me. She said that if I were visiting her at her home, she would’ve cooked something delicious for me, but would I even visit her if she were at home? Sudha ji smiled and sat back on the bench. By now her pallu had fallen off her head and she couldn’t care less. The sun consumed half of the balcony. The monkeys kept jumping up and down on the window ledge.

I asked Sudha ji if she had ever fallen in love.

“Yes, there was a Rajput boy. He looked like a prince. He was very fond of me and wanted to marry me. He even pleaded with my father for my hand. My mother was alive at that time, she refused saying that a Brahmin’s daughter cannot be married to a Rajput. My life would have been totally different from what it has been. But you know what, I am also extremely lucky. Apart from Ajay Banerjee, there were so many men who wanted to marry me. When I stayed with my father for one and a half months, there were four marriage proposals. Some even agreed to adopt my daughter. They offered to admit her in a hostel and bring her home during the vacations. But I didn’t accept any of the offers. I kept thinking about what my daughter would think of her mother.”

I smiled at Sudha ji and said that indeed she was lucky when it came to people falling for her indeed; even in the ashram, she managed to get an admirer. We both laughed at the thought of Sudha ji’s many admirers.

Me: “If there is one piece of advice that you would like to give to your younger self, what would that be?”

Sudha ji laughed at that question. By now tea and puffed rice had been served to the residents. She shared half her bowl with me and asked me to be more specific about which aspect of life she should give advice. I told her that it was her choice.

S: “My advice would be to not trust anybody in your life. Not even your own children. And if you ever do trust someone, make sure that you know that person well enough. Test them well before trusting them.”

Then I asked Sudha ji one of my favourite questions: “If you had a magic wand, what would you do with it?”

I knew that asking her to select one thing that she wanted would be too limited. She had lost a lot, and this was her chance to think and dream of having her life back, even in her imagination.

Sudha ji was very quick to answer. With a faint smile on her lips she said: “I would make a house for myself. Buy things that are essential. Nothing fancy but just what is required. Then I would take back all the property that has been stolen from me. After that I would make a home for vulnerable women. There would be a room, a kitchen, and attached bath. Women who have escaped sex trafficking could live there peacefully.”

She asked me whether I knew the recipes of Bengali dishes like chorchori and shukto. She laughed at my knowing so little about them and taught me some. While Sudha ji spoke I was toying with the fantasy of what would it be like to take her home with me. Not that she’s uncomfortable in the ashram; everything she needs has been provided. The ashram is extremely clean, spacious, and the staff is cordial. But it is not home. I was imagining Sudha ji sitting on our couch, drinking evening tea with my mother, the two of them sharing the day’s events, what to cook for dinner, etc. Within the confines of my mind, far away from reality, it was romantic and ideal.

I also know that Sudha ji was imagining what it would be like if I were visiting her home. She asked me to go visit Tarakeshwar, ask around for her by name, and see her property. While I munched on the butter cookies she gave me, she told me about all the things she would’ve cooked for me.

I gave her my contact information and said bye to her. She came downstairs to see me off and asked for a Hindi to English dictionary and some Hindi magazines and made me promise to take money for the same. “I don’t get to use much of my English, the dictionary will help me brush it up.”

I had spent three hours with Sudha ji while she spoke about her life. It took me almost two days to jot everything down, and I can only hope that I have done justice to her narrative. The story she shared is exclusively hers. Within the labyrinth of her story, there could be many truths, many versions of what she told me, which I do not have the capacity or willingness to prove.

In retrospect, I try and think of why I spent three hours of my life with her. It’s always hard to put into words how feelings affect people, reverberate, and echo within. In this case it’s even harder. The purpose of my project is to ‘listen to inspiring life stories of women who have lost and survived’ and I did exactly that. I heard Sudha ji’s life story of surviving violence, poverty, losing everything she owned, having to rebuild herself, and yet thinking how lucky she is to have so many admirers.

Sudha ji’s experience of looking at life through the prism of violence, abuse, and neglect has made most of her memories toxic. I could see anger, dejection, and detestation when she spoke about her husband, only referring to him by his name. To grow up in a house with a temple, singing bhajans, to eventually stop believing in God for everything that has been taken away from her – Sudha ji is still battling the demons inside her. Demons that don’t let her rest, accept or feel at home anywhere in the world. She’s a seeker. A seeker in a world that doesn’t allow women to demand or look for more. Sudha ji is looked down upon by the home authorities for not being ‘spiritual’, not being friendly with fellow residents, for being too forward and asking for things from people.

Sudha ji’s indomitable spirit made me question if I was settling down for too little, if there was more that I should ask for, and if there is more that I deserve. She also made me feel the power of hope to continue on a quest believing that it can be accomplished. I am indebted to Sudha ji for teaching me to look beyond black and white and see the other colours.

Cover Image: Flickr/(CC BY 2.0)