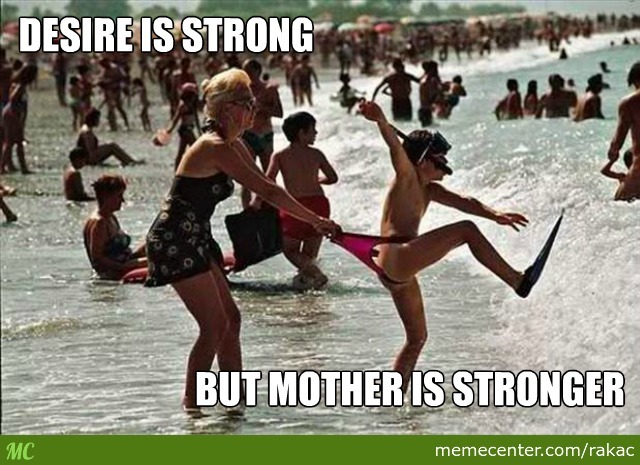

Desire, one may think, is personal. Hard to imagine that desire encompasses a world of conflict and upheaval, engenders shifts of understanding and hard fought battles across law, politics, family, society, education, psychiatry, and other disciplines and occupations, while also inspiring art, music and creative expression. All this while sitting pretty central to the human spirit, clinging on resiliently, even as the individual human being, or an institution, may ignore desire, laugh at it, misunderstand it, battle it, repress it, give in to it, or seek to identify and fulfill it. Across identity and culture. In waking moments and in dreams. Against the desires of our mothers and significant others, or in line with those desires!

What is desire? Dictionary meanings are available to all, and include explanatory words such as wanting, longing, pining and craving. But what is desire as intrinsic to life, human and non-human? That question assumes that desire is intrinsic to life, just as is sexuality, both aspects integral to identity, both aspects beset with conflict, full of tragicomic potential. It is telling that in lists such as this, attempting to compile items of desire, sex and sexuality don’t figure. There is money, there are children, and there are dream weddings. No sex, no sexuality. Perhaps desire in the sexuality khichri is hard to handle, given that sexuality itself is such a hot potato.

Yet whether the word desire is used or not, it lurks beneath the surface causing us to do or be, or not, to accept, to reject, or not. Desire is an uncalibrated and uncalibratable measuring tool of why we feel anything that we feel about life. Perhaps if we look desire in the eye we can finally face our own human sexuality.

What part does sexual desire play in our lives and our choices? One could argue that it depends on what part we allow it to play. Stuffed like jack into the box, the only part it can play is a scary one. Julie Bindel, in an online piece, says:

“I remember the graffiti on a wall in Leeds. “My mother made me a lesbian”; and underneath: “If I gave her the wool would she make me one?” Thirty years since homosexuality was removed from the list of recognised mental disorders, scientists persist in searching for a “cause”, refusing to accept that sexuality and sexual desire are social constructs, not biological or genetically determined.”

While this article is being written for the August 2018 issue of In Plainspeak, a five-judge bench of the Supreme Court of India has been hearing petitions on Section 377 of the IPC that seek to decriminalise homosexuality and protect the rights of LGBTQ people. It is expected that the Supreme Court order on the issue will be out later this year. In 2009, the Delhi High Court came out with a progressive judgement on the issue, cheered by many, decriminalising homosexuality. This was the result of years of activism by groups and individuals who came together to fight for the right to live with freedom and without fear of being discriminated against, abused and picked upon based on sexual orientation and preference. In 2013, the Supreme Court set aside the Delhi High Court decision in a regressive ruling that was a massive setback to the LGBTQ movement and the fight for rights. Five years later, today, the issue is back in court, and this time there is hope that the court will take a progressive approach that upholds rights and justice. Justice Chandrachud, one of the five-judge bench, is quoted in media reports as saying, “Our focus is not only on the sexual act, but the relationship between two consenting adults and the manifestation of their rights under Articles 14 and 21…we are dwelling on the nature of relationship and not marriage…we want the relationship to be protected under Fundamental Rights and to not suffer moral policing”. This is indicative of the current stance of this bench, of rights activists and of progressive groups and individuals – and it brings hope. It is perfectly feasible that desire often plays a part in these relationships under discussion.

Even as this matter is heard in court, there is another also knocking at the doors of law and justice – this has to do with adultery, and Section 497 of the IPC that punishes the man, not the woman, for adultery. The concept of adultery assumes marriage and sexual infidelity within marriage. Last month, we interviewed Madhu Mehra, founding member and the Executive Director of Partners for Law in Development (PLD), who speaks of the adultery law in India in her book The Rape Law and Constructions of Sexuality, saying that “Adultery is a ground for divorce for either spouse under the marriage laws, therefore making it a civil wrong between two persons. Yet, when committed by the wife, it is treated as a crime!” What is most worth noting about this law is that this ‘crime’ entails a punishment of imprisonment that could be for five years, for ‘he’ the lover, while the wife is not to be punished. Last year, the Supreme Court admitted a petition from Joseph Shine, to drop Section 497 of the IPC. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud is quoted as asking whether by presuming the woman to be a victim,the law has made a patronising assumption. Now, as always, when issues of sexuality and rights enter the discourse, the ‘institution of marriage’ faithfully makes its appearance. Again this institution, that many may argue also requires investigation and questioning, has been raised as a front for countering the petition, as the government tries to have it dismissed, reportedly because “The decriminalisation of adultery will result in weakening the sanctity of a marital bond and will result in laxity in the marital bond”.

One may imagine there are many reasons for adultery, one of which is possibly love, and another possibly, is desire, and sometimes both together. To punish for either love or desire, and to think of making this fall within the purview of the law even when such love or desire is expressed between two consenting adults, is worth debate. Further, when such love or desire is ‘punished’ by making only the ‘he’ who is the lover, punishable, by imprisonment, not she who is the ‘wife’, there is reason to pause and think of the implications of this. It would appear, using the lens of this law, that a woman has no agency in the matter of relationships, sexuality, adultery, marriage, love, desire. It is time to ask whether desire belongs to one, but not to another, and why.

Speaking of marriage, the Governor of Goa, Mridula Sinha, also an author, has just forced the students of Goa University, at their convocation ceremony, to take a ‘pledge’ that, “Once married, you will not break the relationship on small reasons. You will strive to make the marriage lasting and happy. You will strive to respect each other”. It is important to investigate multiple aspects of this interaction. Who is giving a message, to whom, at what event, why in the form of a pledge, and what impact may it have on an individual, and on an institution (marriage) where violations of rights that some people may consider ‘small’ of ‘small reasons’ are rampant. In a 2015 interview with Defence and Security Alert, Mridula Sinha is quoted as saying, “In traditional India, family and village or locality owned the responsibility of safety and security of women and now it’s missing. There is deterioration in ethics and value based education in the society. The society needs to inculcate value based education in the children.” In a 2016 article she also spoke of how her father saved her life because her mother, when pregnant with her, had wanted an abortion. There are some unspoken assumptions and messages here but the main takeaway is that it is the institutions, or the men, that hold the key to issues that affect women, be they safety and security or personal, life-altering decisions. Space to question the institution(s)–family, village, locality, society–does not exist. Women remain without sense of self, cogs invisible within the machine.

Mridula Sinha has authored a book called Flames of Desire, an intriguing title. A quick word scan of this book using the keyword ‘desire’ reveals long discussions between protagonists, or soliloquies and messages, where words like soul, pleasure, intoxication, consuming, obsession, arousing, fulfillment, physical, merging, cessation, and other such, leap out like dancing devils. It is not out of place to wonder why these words do not find space for open discussions with students who are about to set off into diverse journeys of adulthood, instead of requiring them to take blanket pledges with gaping holes in them.

Consider the status of desire in such a situation. Any desire, not necessarily or narrowly sexual, but perhaps related to sexuality, such as independence, equality, gender role-bending, controlling your own finances, eating the food you’d like to eat as opposed to the food your spouse desires, wearing the clothes you’d like to wear, birth control, choosing to have or not to have children … any of these desires would have only that importance that the individual concerned is able to apportion to it. Only that importance that the individual concerned is able to channel to it, the degree to which they are able to acknowledge, protect and promote it. Internet blogger Yamini Bhalerao, writing about Indian marriages states it quite simply, “Like our households, the bedrooms in India run according to the dictates and desires of the male partner.”

In a situation where gender inequality is the norm, in a marriage where sexuality and the notion of equal rights within the marriage does not exist, the desire of the party in power will certainly dominate over the desire of the unequal other.

We return to the question, what is desire? Madhavi Menon, author of the book Infinite Variety; A History of Desire in India says in an online interview, “There were well over a thousand years of Indian literatures, arts, and societies that contributed to a complex understanding of desire. But when the British came, they picked the most conservative of these understandings – for example, from the Manusmriti – and used them as a launching pad for their own morality. And today, that particular version of Victorian morality cum caste purity has become the “official” narrative about Indian desire. However, we continue to live in ways that indicate histories of desire ignored by this narrative of prudery – our comfort with hijras, for example, or our passion for Sufi poetry, or our belief in gender-bending gods.” She goes on to say: “Desire is never straightforward, and it cannot be straitjacketed – in fact, there is nothing straight about desire at all”.

It’s interesting, that use of the word straitjacket. Psychiatry has a term called desire disorders. These once included sexual aversion disorder (SAD). It is important to consider how psychiatry sticks its finger into thought, feeling and behaviour confident that therapy and medication is a cure all. That is being questioned by some who have experienced the system, from any vantage point – client, doctor, caregiver. SAD has been removed from DSM 5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual), though not everyone is happy without SAD. Once, not too long ago, homosexuality was also in the DSM. It was removed in the 70’s but replaced with ‘sexual orientation disturbance’. This went out of the DSM in 1987. Desire and the lack of it are considered so crucial to life and relationships that they must be regulated (by who?) by any means possible. Why?

It is possible to question whether desire or the absence of it, is a disorder. It is important to ask why, and to ask who is labelling what desire as a disorder. Then we must also question what happens to desire that is not acceptable. The clichéd question here revolves around whether women are meant to feel sexual desire, and on the basis of this, initiate a sexual engagement or interaction. These are very complex questions when one adds layers to the view, a mental health layer, a social norms and cultural acceptability layer, an institution of marriage layer, an adultery layer, and so on.

We live in exciting times. Right or wrong, these questions and others are emerging in art, entertainment, society and culture. The writer of this piece on the portrayal of women and desire in Indian cinema, points out “A woman who gave into her ‘carnal desires,’ as we saw in movies like Julie, was socially ostracised and labelled a scarlet woman. When Meena Kumari in Sahib, Biwi Aur Ghulam begged her husband to spend the night with her, (her aim being to have a child, and not so much sexual fulfilment) and not with a nautch girl, she has to agree to drink alcohol in order to lose her inhibitions, the implication being that unless she does so she will not be able to pleasure her husband in the manner he is accustomed to.” In Lust Stories, which released on Netflix in June this year, film-makers and actors present female characters exploring their desires. Most interesting is the use of words, as fuck and fornicate enter the dialogue in a style quite suited to airing and shaking out unused and mildewed items at the back of the old wooden cupboard.

Not everyone will agree with everyone, not everyone will like everything, but there is an unfolding expression and exploration of desire and it is streaming into people’s lives, like light through cracks in fortress walls. High time.

Cover Image: Flickr/(CC BY-SA 2.0)