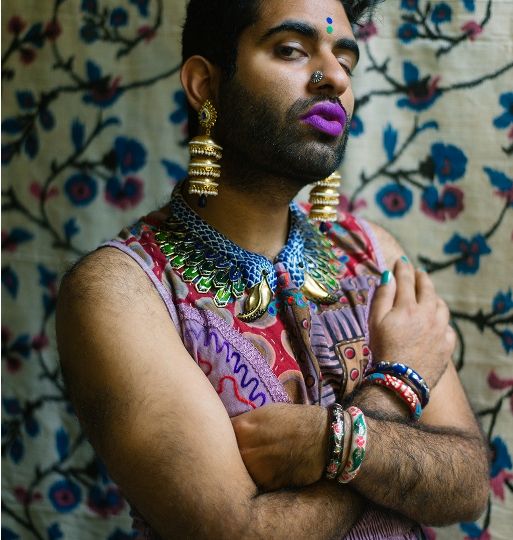

Alok Vaid-Menon is a gender non-conforming Indian-American performance artist, writer, and educator. Their poetry, for which they became the youngest recipient of the prestigious Live Works Performance Act Award (granted to only 10 performance artists across the world), constantly questions binaries of gender and sexuality, and seeks to create awareness around important LGBTQ issues. In an e-mail conversation with TARSHI, Vaid-Menon talks about the norms of performativity and of poetic performance.

TARSHI: You’ve grown up in a conservative part of Texas. How has that impacted your journey towards embracing your gender identity and your notions of sexuality? Have your Indian roots also played a part in this journey?

Alok Vaid-Menon (AVM): Growing up amidst extreme conservatism and religiosity taught me the power of my queerness. Something so small and irrelevant like how I walk and gesture and the tinge in my voice had such a catastrophic impact on the feeble imaginary of my peers. It was a constant lesson: both that people have been taught to fear the very things that have the potential to set them free, and that there are no such things as LGBTI issues, there are just issues that people have with us. What is the queer struggle but the unfettered imagination of other people?

I also learned the reality of physical and sexual violence – experiences and lessons that continue to inform the urgency in my work today. These topics are not just theoretical, they hurt in all senses of the word.

I don’t think we can point out exactly where and how our race informs our gender and vice versa – there are already always a confluence of factors that are so complex it feels impossible to parse out where one thing begins and where one thing ends. What I can say is that I grew up in a tight-knit Indian/Hindu/upper-caste community that was deeply concerned with scrutinising and regulating sexual and gender norms. It took me a long time to reconcile my queerness with my Indianness when they were framed to me initially in such an antagonistic way. But I’ve since come to appreciate the delight of failing to uphold the norms – another way of being free, I think.

T: As someone who’s trans-feminine and nonbinary, have you ever experienced the pressure to ‘pass’ as a certain gender? Has that affected the way you perceive your own identity or body?

AVM: I feel that pressure every day. I experience harassment every day I go outside or every time I post online, precisely because I don’t look like a “man” or a “woman.” Every time I experience violence in public it’s a form of pressure to police me into looking like a “man.” When I speak about the constant vitriol I endure, many feminists do not believe me because I am not a woman (another form of pressure). When I speak about my struggles with trans people they often tell me that if I “looked more convincing” (in other words: sought to look like what society dictates a woman should look like), I would experience less violence. There are actually very few people in the world who I have found accepted me for me on my own terms without projecting what I should look like in order to make other people more comfortable.

T: Does this pressure to ‘pass’ also affect how you negotiate your sexuality? Are there a set of assumptions or bounds set on the ways you explore your sexuality?

AVM: Yes. The majority of violence against trans and gender non-conforming people is from our intimate partners. Because people cannot reconcile their desire for us with their conceptions of who they are and their own identities, they turn that desire into violence. There is a deep and intimate connection between desire and disgust that trans-feminine people know very well. I have to constantly negotiate an onslaught of projections, fantasies, nightmares interchangeably imposed on me. It’s difficult to feel like I own my own body and my own sexuality when they are so contested by other people’s fixations about them.

T: How does the performance of your gender intersect with the performance of your poetry? Are these two forms of performances dependent on each other, or do they function in different ways?

AVM: We are constantly trying to maintain the fiction that things are separate and discrete which is already always the myth of purity. What I have learned in my life is that everything spills into one another. Contamination is the norm. This is why borders, binaries, and boundaries are irrelevant. The pulse and flow of things will always – inevitably – surpass the edges. So yes, my performance art is my gender is my performance art. It’s difficult in this iteration of society being both a performance artist and a trans person, because cis people already always dismiss our genders as “artificial” and “performative.” So we have to say, “No, what I am is real!” But why can’t there be authenticity in performativity? For me, performance is actually one of the only ways I can access the real.

T: Your poetry and your writing are deeply political, exploring the nuances of the trans experience as well as the external social factors that influence it. Is that a conscious choice, or do you feel that there’s an added pressure for your art to be political because of the marginalised experience you embody?

AVM: In order for the world to maintain the myth of two genders and sexes, intersex and gender non-conforming people have to be made invisible. For me to be here saying “I exist” is already always political. Besides, all art is political. There is no “apolitical” art in a profoundly unequal world. To create in a world hell-bent on destruction is already political. It’s not just marginalised people who create political work. Privileged people drawing landscapes and taking photographs of buildings is political – there are all political choices being made here.

T: Is the experience of performing your poetry in India different than it’s in the West? What are the differences or similarities in the reactions or the feedback you receive?

AVM: Once again I would question the inherent separateness of “India” from “the West”. My work is in English and about my experiences navigating the United States so the people who come to my performances in India tend to be of a particular upper class and caste composition. And many people who come to my shows in the West are of the South Asian diaspora. The differences that I experience in my crowds have more to do with what’s going on in the world – hell, what’s going on that evening in individual peoples’ lives, what energies and ghosts they are bringing to the room with them.

T: In your writing and in previous interviews, you’ve frequently talked about ending the gender binary completely. What would that entail? How would that affect the way the performativity of one’s gender is realised?

AVM: At every level we have been so saturated by the gender binary and all of its insidious logic that it often feels impossible to imagine what it would look like to dismantle it. Rather than getting fixated on theory I try to think about every day interventions: supporting trans and gender non-conforming people who have and continue to be on the frontlines of this struggle, actively challenging my own and the people around me’s fixation on gendering everyone and everything, creating spaces and environments that encourage people to try, experiment, become. I don’t really know what a post-gender world would look like but I can imagine that we’d feel more free, loving, compassionate. I also hope the fashion would be better!

T: What about gender-specific pronouns? Are they too, a form of gender performance, or of ‘passing’?

AVM: Gender specific pronouns can mean what we want them to mean. He doesn’t have to mean boy/man/opposition to woman she. It’s less what we use and more how we use it.

T: The popular notions of ‘trans’ sometimes also end up becoming a binary – either trans woman, or man. Do you find the nonbinary experience getting erased from such narratives? How do you, then, navigate both trans and cis feminist spaces as a nonbinary person?

AVM: Yes absolutely. It’s deeply distressing that as the years pass I am being called not “legitimately trans” because I am not interested in pursuing medical transition. The depths of historical erasure in this are staggering; departures from the Western gender binary have always been.

Truth be told, I am rarely invited to cis and trans feminist spaces. In fact, I am often prohibited from them. But when I am there I try to have everyone understand that the existence of oppositional and mutually exclusive categories of “man” and “woman” is the problem – that the goal is not about making everyone nonbinary, but about making “man” and “woman” two options of many. Increasingly more and more feminists are getting on board with this, which is great!

T: Cisgender discourses about trans lives also often unnecessarily revolve around genitalia – ending up either fetishising or demonising trans bodies. In such cases, how important do you think body-positivity or sex-positivity are within trans and nonbinary individuals?

AVM: I would say it’s not just cisgender discourses, but all discourses themselves. Trans and gender non-conforming people are also deeply implicated in the reduction of our own existence to our bodies and our genitalia. It involves constant work to remember and imagine otherwise. I’m not sure if body/sex positivity is the answer. There are good days and there are bad days. I am aspiring toward accepting all of them. We shouldn’t have to have a positive relationship with who we are and what we look like – especially in a world that constantly demeans us. My body is not “bad” and nor is my body “good” my body just “is”, and that should be enough.

T: India is getting ready for a judgement that may possibly read down Section 377, the law that criminalises same-sex sexual relationships in India. What are your thoughts on it? What kind of impact do you think that would have on the sexuality of trans or nonbinary individuals in the country?

AVM: I will defer to the trans and gender non-conforming activists on the ground in India who have a better understanding of this. What I will say is that I am sceptical of legal changes which often seem more symbolic than anything. I’ve seen how changing laws and policies doesn’t change hearts and minds. This is where we need artists to shift culture and movements to apply pressure – legal change has to be part of these larger multifaceted strategy otherwise it won’t do much.