In this article I explore how information and communication technologies (ICTs) are blurring and redefining subjective experiences of class and sexuality for adolescents and young people in India. The questions that guide this are – Can the online space and young people’s engagement with it shift the class-based bias in how content on sexuality is consumed as well as produced? How does the broader reach of sexuality content enable those who are otherwise limited by material and structural constraints to develop a more expansive and informed worldview about sexuality? Does access to content through digital interventions allow young people to find loopholes in the otherwise rigid cultural and social norms that continue to exert control over their sexuality?

***

To be able to explore these questions it is important to first examine young people’s access to and use of digital technologies. Data collected as part of a research study by the Population Council titled `Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA)’ in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, India and published in 2017, provide important insights about young people’s access to mobile phones, internet and social media. Findings from Bihar[1]show that penetration of internet and social media remains limited but is growing, parents still exert considerable control over young people’s access to the Internet and there is a significant rural and gender disadvantage in access to information and communication technology. One finding that does stand out is the fact that for those that are able to access content over phones and the Internet, sex is not an unmentionable topic. In the study this was measured through a question about respondents’ exposure to pornographic material. This study provides robust user-centric data about young people’s access to and use of digital media. It confirms the earlier anecdotal understanding about the growing diffusion of technology, particularly mobile phones, in rural and urban populations, among genders, across wealth quintiles and those with varied educational attainment.

Since the time of the study, that already highlighted the growing trend with regard to young people’s access to and use of mobile phones, significant transformations have taken place. The Mary Meeker annual Internet trends report for 2017[2] highlights two major factors driving this. The first is the decline in the prices of smartphones, and the second is the fall in Internet data prices, which was to a large extent spurred by Reliance Jio – the telecommunications arm of India’s largest business conglomerate – that launched its service in September 2016. It offered free data to users. This resulted in large numbers of users of mobile phones, particularly young people, being able to afford Internet services and also forced other service providers to reduce the cost of their services.

Cheaper access to ICTs has served to reduce barriers that exist for those from marginalised economic and social classes to access information and entertainment and enables a different sort of social mobility that is delinked from actual material and social constraints measured in terms of education and occupation. More importantly, and specific to this article access to the digital world has served to open up past restrictions with regard to who is able to consume and produce content related to sexuality.

***

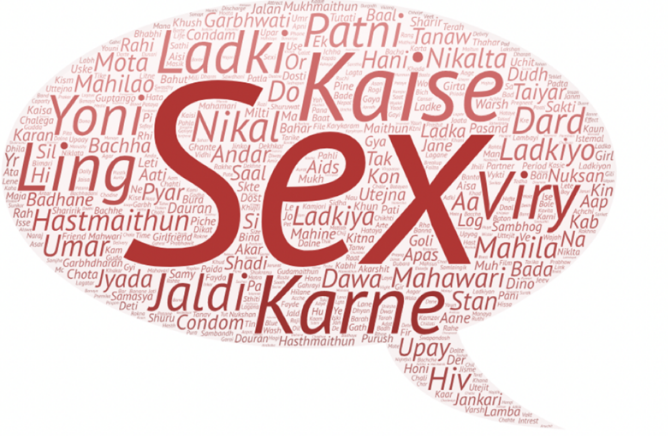

What is it that preoccupies most young people? This is again something that is anecdotally known through offline engagement. However, now as a result of a number of online digital and technology based interventions we have more `data’ to support this understanding. In this article I use the example of a mobile phone based interactive voice response system (IVRS) platform Kahi Ankahi Baatein(Saying the Unsaid) that provides sexual and reproductive health and rights information (SRHR) to young people. This platform is jointly run and managed by CREA, TARSHI, Gram Vaani and Maara. One of the channels on this platform is a Sawal-Jawab (Question and Answer) channel. Callers can record questions answers to which are posted on the infoline. What are the callers posting on? The leading topics include myths and misconceptions with regard to sex, sexual desire, consent and relationships, sex and pregnancy, sexual problems, masturbation, relationships and contraception, safe sex, puberty, virginity and homosexuality. A voluntary survey administered as part of the infoline provides important data with regard to the background of callers. Till date calls have been received from practically every State and Union Territory in India. Demographic profile of callers: 70 percent male, 27 percent women and 3 percent transgender persons. More than half are unmarried (69%), more than half the female callers (55%) report being below 18 years of age and the male caller profile of those below 18 years is also close to 50 percent.

In unpacking class as a social category through the lens of young people accessing SRHR content via an infoline it is possible to conclude that broader reach of sexuality content does enable those who are otherwise limited by material and structural constraints to develop a more expansive and informed worldview about sexuality. It is also possible to claim that accessing content through digital interventions allows young people to find loopholes in the otherwise rigid cultural and social norms that continue to exert control over their sexuality.

Social mobility in contemporary, digitally driven lives needs to be understood differently and beyond material conditions that typically denominate class and determine class-based norms and barriers. The online space can increasingly becomes a site for sexual and class transgressions.

Social and material barriers too can appear to be diffused as the online space unlike public sites begins to offer diverse people from varied backgrounds ‘egalitatrian’ access to information related to sex and sexuality that is otherwise inaccessible for them. One domain where this happens is the way language and terminology shift as a result of the opening up of online space to diverse audiences. Examples of this can be seen not just on the IVRS platform Kahi Ankahi Batein but also other online platforms such as Agents of Ishq, Feminism in India and Love Matters all of which have broadened their approach to produce and ensure interactions in Hindi on topics related to sexuality that has opened up space for diverse engagement.

In conclusion, the limited point that can be made is that technology has helped mediate class-based distinctions in the way young people are able to access information on sexuality. This provides a momentary illusion of transcending class-based limitations. There is something to be said about the radical potential of more people, particularly those that have traditionally been excluded from accessing information and having voice, to be able to transform the nature and content of the conversations we have on sexuality. This article, however, does not seek to make the claim that this in anyway transforms the material and structural constraints that define the subjective experience of class and sexuality.

[1]Santhya, K.G., R. Acharya, N. Pandey et al. 2017. Understanding the lives of adolescents and young adults (UDAYA) in Bihar, India. New Delhi: Population Council

[2]Mehta, Ivan, 2017. Reliance Jio Is Driving Indian Internet Growth, Says The Mary Meeker Report

https://www.huffingtonpost.in/2017/06/01/reliance-jio-is-driving-indian-internet-growth-says-the-mary-me_a_22120777/

Accessed on 23 May, 2019

Cover Image: Pixabay

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।