In this article, I am interested in exploring the entanglements between privacy and secrecy through the lives and experiences of intersex people. Privacy can be a double-edged sword in relation to sexuality. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, privacy is defined as “freedom from unauthorised intrusion,” whereas secrecy means “the condition of being hidden or concealed.” Privacy has often been used as a justification to maintain separation between the law of the land and people’s lives.

Through my current doctoral research on exploring factors that guide decision-making related to gender assignment of intersex people in India, I have had the opportunity to meet with and interview many medical professionals across different specialisations on how they arrive at a decision on a person’s gender. Additionally, I have also interviewed a few families of intersex people on their participation in these decision-making processes and a few intersex adults on their lived experiences. Intersex people could be defined as people whose bodies do not fit within the gender-binary norms of what is considered a typical male or a female body. As such, they may present several variations including in external genitalia, internal reproductive organs, chromosomes, hormones or a combination of these. Because their bodies may not adhere to strict notions of maleness or femaleness, they are often subjected to medical interventions to make them conform to one side of the gender binary. These interventions could include hormone replacement therapies and ‘corrective’ surgeries, which are often not a one-time intervention and may continue throughout the person’s lifetime. While a few of these surgeries and interventions may be essential and lifesaving[1], most of the interventions are done so that bodies may adhere to a binary logic of sex and gender. Because many of these surgeries and interventions are initiated when the intersex person is very young, they are rarely included in the decision-making process. Many of these interventions are therefore non-consensual and often with irreversible outcomes.

In discussing the lives of intersex people, a common narrative that doctors related was the need for early detection and ‘corrective’ interventions on these bodies. Doctors often narrated to me the importance of early detection of these intersex variations so that interventions could be carried out at the earliest. Time is therefore of the essence. The earlier the detection and ‘correction’, the ‘better’ and ‘neater’ the bodies and the lives of these intersex people. Sometimes, the justification provided for these surgeries is to protect intersex people from potential malignancies[2]. In cases where the variations may not be so apparent (many intersex variations may not be easily detectable and thus it is possible for people to go through their entire lives without the knowledge of their intersex variation), intersex people may also approach doctors later in life, thus deferring medical interventions and decisions on their bodies.

Something that was common to many of these narratives is the secrecy that is maintained regarding these lives and their bodies. The secrecy could be about the nature of the variation as well as about the interventions carried out on these bodies. There is significant anecdotal and research evidence globally to show that many intersex people had no knowledge of their variation and/or the nature of the interventions carried out on their bodies for several years. Secrecy could also be maintained at several different levels– some doctors mentioned that although they shared some aspects of these variations with the family members, they considered such information to be too complex to share the full nature of these decision-making practices, especially when the service users came from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds with low education levels. Going by the rigid and hierarchical nature of the doctor-patient relationship in the Global South context, it is not hard to believe that a lot of information may be kept from the families because doctors may believe that they (the doctors) were in the best position to decide. Besides, families, being used to this hierarchical relationship and inaccessible language used by doctors, may also believe it best to go along with the doctor’s wishes. In many of my interviews, doctors narrated that they did disclose the variations and some of the interventions necessary to the family members. There were times doctors mentioned that they were heavily dependent on the family members’ consent to go through with the medical interventions. However, the extent of the information shared with the families and how these interventions may (or may not) impact intersex people’s lives, may not be completely clear and needs further interrogation.

Most doctors, however, said that even if they might share some of the details with the families so the family members could participate in deciding the gender of the child, in most cases the intersex children/people were not involved in this process[3]. The doctors justified this by saying that since some of these families approached them when the children were quite young, the children’s participation in this process could not be expected. Even in cases where they may be older, it may depend on the families as to whether, when and to what extent such information was shared. A paediatric surgeon also mentioned that in cases where the intersex people were older and have continued coming to the doctors for a variety of interventions and issues through their life cycle (some have approached doctors to seek counselling along with their partners when deciding to get into a marriage, or soon after), it was often a secret that intersex people and their families shared with these doctors, with the latter thus becoming a secret-keeper or a confidante in the process. This is illustrative of not just the role doctors are called upon to play in patients’ lives but also reminds one of the lone struggles of these intersex people and their families in trying to make meaning of their bodies, the interpretations of these bodies and their life experiences.

Levels of secrecy were often strong when it came to hiding aspects of the variations or other details from extended family members, neighbours and/or other friends. Secrecy is maintained almost as a ritual in some of these cases where parents are often counselled by doctors to retain this information only among the inner circle of the family. If the variation is detected at birth, the infant is often kept in the hospital till a battery of tests can be conducted and a gender can be assigned by the doctors. Until then, families are encouraged to defer giving any information to other family members. The decision related to gender assignment for birth registration is extended for as long as possible until such gender can be assigned and announced to all and sundry. In instances where the variation may have been detected much later (not during infancy), it is very likely that these people were already assigned a specific gender and had been adhering to the identity, behaviours and roles normatively attached to that gender. In many such instances it was perhaps easier for the intersex person and their families to carry on with the gender that had been assigned already. However, doctors related situations where either the intersex person was not happy in the gender assigned or the doctor felt more strongly about assigning the ‘opposite’ gender (it is always considered ‘opposite’because gender in these situations is always presumed to be a binary). In such situations, not only were ‘corrective’ interventions carried out to assign a ‘neat’ sex/gender to the intersex person, but in many instances the families had to move away to a different home and city to live fresh lives away from known and familiar territories.

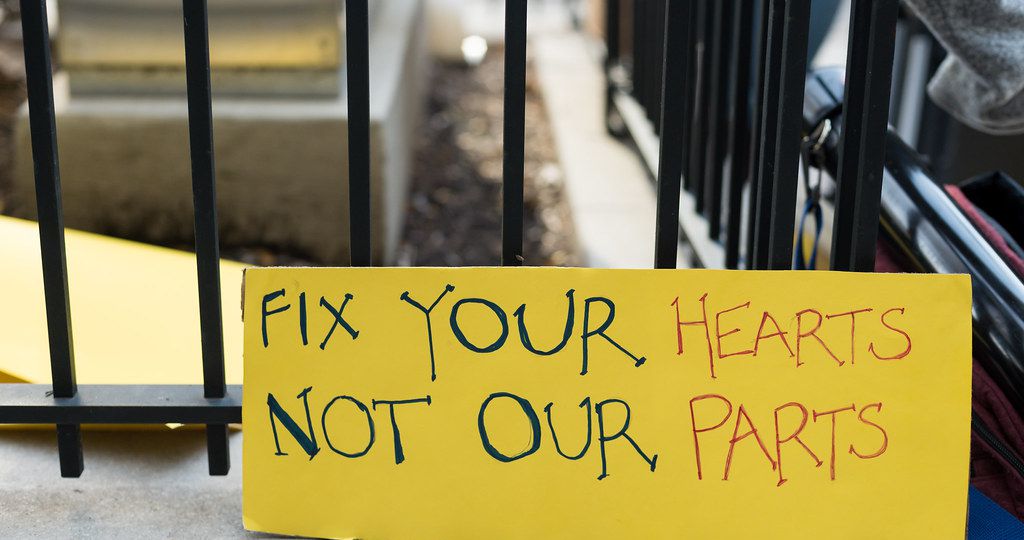

A justification provided for these layers of secrecy is often the shame attached to these so-called atypical bodies, that is, bodies which are often construed as ‘abnormal’. The norms around which sex and gender are constructed are often randomly decided.However, non-adherence to these norms subjects these bodies to discrimination and pathologisation with many of them being subjected to ‘corrective’ mechanisms throughout much of their lives.While one’s genitals are often labelled ‘private’, bodies are regularly subjected to societal scrutiny. In the case of intersex people the monitoring and regulation becomes even more magnified. Because of the variations and non-conformity that intersex bodies present, they are further covered in layers of secrecy. This secrecy is sometimes packaged as privacy which must be maintained at different levels – at the level of clinicians, at the level of families, societies and to the intersex individual. In such instances, privacy can become an important factor to maintain such secrecy. However, what is also important to observe in these instances is that the private nature of one’s body and the functions that it can (or cannot) perform is often kept from the knowledge of the intersex person themselves. Such secrecy or hiding away of important information about one’s sex and gender is maintained with the justification of protecting the person against shame and discrimination. Thus, private lives and experiences are kept a secret from not only the society – while the performance of a neat sex and gender are enacted – but also often kept a secret from the person themselves thus leading to a messy enmeshing of privacy with secrecy. This entanglement of privacy and secrecy is often enacted with the idea of protection, that somehow this knowledge may harm the intersex person themselves. How might then we make sense of privacy? If secrecy is something that is maintained from others (and yet the private nature of people’s lives is being kept secret from the person themselves by doctors and the families), must the boundaries around which we draw our private lives be redrawn? For intersex people, privacy or the ‘freedom from unauthorised intrusion’ is constantly violated in which many a times knowledge about their bodies and the interventions carried out on their bodies are not made known to them. And yet, they keep going to doctors where their private bodies are often rendered available for observation and regulation. Privacy in these instances is thus constantly being re-negotiated and re-drawn.

[1]Certain medical interventions may be considered necessary in certain variations for example to manage the ability to urinate or in certain salt wasting variations. To read more, please refer to: https://ihra.org.au/bodily-integrity/.

[2]Interventions based on potential malignancies may not be adequately substantiated and may be based on limited research and/or small sample sizes (Carpenter, 2018).

[3]This was especially followed in cases where the intersex people were young. There were however a few doctors who mentioned that they tried to include older intersex people in some of these discussions. However, the decision to include intersex people and the determination of the age at which they could be included in these conversations varied across doctors.

Cover Image Source: Sarah-ji, Flickr