I turned 15 in 2003, awkward, shy and glaringly Roman Catholic. I lived in Gujarat, in a city blinking and stumbling into an uneasy post-Godhra way of life. Even before the riots, being Catholic clearly positioned me on the margins of mainstream life. Now, with the riots behind us, life felt a bit like swimming in a pool you thought you knew. The water felt familiar but your feet could no longer find the floor. My family and community were silently renegotiating relationships with Hindu friends, neighbours and colleagues. My sister’s Hindu hockey team-mate spoke disparagingly about their Muslim team-mate after a match. Our neighbour was suddenly saying ugly, hateful things about Muslim friends we had in common. Hyper-aware of our own minority status, we did not dare say anything in their defence. And then, American author Dan Brown’s novel The Da Vinci Code released to a great storm of Catholic outrage.

The mystery/thriller The Da Vinci Code is set in modern day Paris and its plot is driven by the speculation around a sexual relationship between Jesus and Mary Magdalene. The book opens with its protagonist Robert Langdon, a professor of Symbology at Harvard, being framed by French law-enforcement for murder. He escapes interrogation and makes his way through the novel solving puzzles and decoding riddles, finally uncovering a long kept historical secret: Jesus and Mary Magdalene had children together. The book is fast paced with short chapters ending in cliff-hangers.The action is often interrupted when one of the characters (either Langdon or another character Teabing) serve as mouthpieces for long-winded explainers on History, Art or Religion. These monologues, by themselves quite dull, play for shock value in terms of what they reveal: the Vatican’s cover-up of the true nature of the Holy Grail and the work of secret society, The Priory of Sion.

In one such monologue, Teabing, a British Royal Historian, pulls out a volume titled The Gnostic Gospels, and points to a passage in the Gospel of Philip (a gospel which isn’t included in the The New Testament Bible that Roman Catholics use) where Jesus is described as kissing Mary Magdalene on the mouth.I remember reading this with a mix of grim fascination and growing revulsion. It wasn’t so much the kissing that upset me,but the fact that it was Jesus doing the kissing.

I could not imagine kissing the boys I liked at the time. Touching lips was something the blonde girls in my Sweet Valley High books did during “detention”, after “cheer leading practice” or before “homeroom”. Where would brown teenagers like me kiss? The gully outside school? Under my building, in full view of so-and-so Aunty on the second floor? After, Heaven forbid, Sunday Mass? Logistics weren’t the only obstacle. I was also held in check by internalised messages of what constituted being a good Catholic girl: no kissing and no fooling around until after you say ‘I do’. Of course, many religions wield power by closely controlling female sexuality, so I have no doubt that I was in good company with Indian girls from all kinds of backgrounds. Yet, being Catholic in Gujarat meant that I could not afford any slip-ups. I could not reject the mantle of respectability, because it was a mantle that was hard-earned and easily revoked. Often, I was told that the eyes of the Hindu majority were on us, constantly watching and waiting for a chance to call us ‘Western’ which was code for ‘depraved’ or ‘forward’. And of course there was that other thing.

I was being raised by a single mother. In my particular context, there were only two reasons one left a husband. He was an alcoholic who beat you or he was an alcoholic who didn’t work. My father was neither of these things. In fact he wasn’t an alcoholic at all. My parents were simply incompatible, but being incompatible was not considered reason enough to break marriage vows made before God. My mother raising her children by herself meant that even within our close-knit community, we were an anomaly; the absence of a Man of the House was conspicuous and odd. “People are watching,” my mother used to tell me, “They are waiting for the chance to say,‘Oh she comes from a broken family.’ Don’t give them that chance.”

I therefore trained myself to follow the rules. I started to look at my body and my sexuality as something to hold in check, to tamp down. As I grew up and had my series of firsts– my first kiss, my first time being touched, having sex – I couldn’t shake the feeling of it all being illicit, of being watched by numerous eyes. These eyes would see me as Catholic and therefore ‘Western’ and therefore ‘depraved’ or that girl who came from a broken home and was therefore acting out. I viewed my body and the myriad ways it could give and receive pleasure as secondary to my mind and my emotional life, which I had ‘permission’ to nurture guilt-free. I remember writing an analysis of female desire in the 1975 film Julie for my MA dissertation with a sort of smug academic distance, not looking inward at the ways in which I experienced desire, not reflecting on what had formed and shaped my attitude to sex and pleasure. All this is of course by way of saying, there was no kissing on the horizon for me at 15.

Yet here was Jesus, the most sexless entity in my imagination, a God-figure whose likeness was on calendars and pictures all over my home, whose very existence resulted from a VIRGIN birth, busy having a sex life instead of preaching on the Mount or healing lepers. It threw my orderly world into absolute turbulence. Besides, other girls in my school – Hindu girls – were also reading the book. I broke into a sweat at the thought of being asked to defend this truly scandalous behaviour by my God.

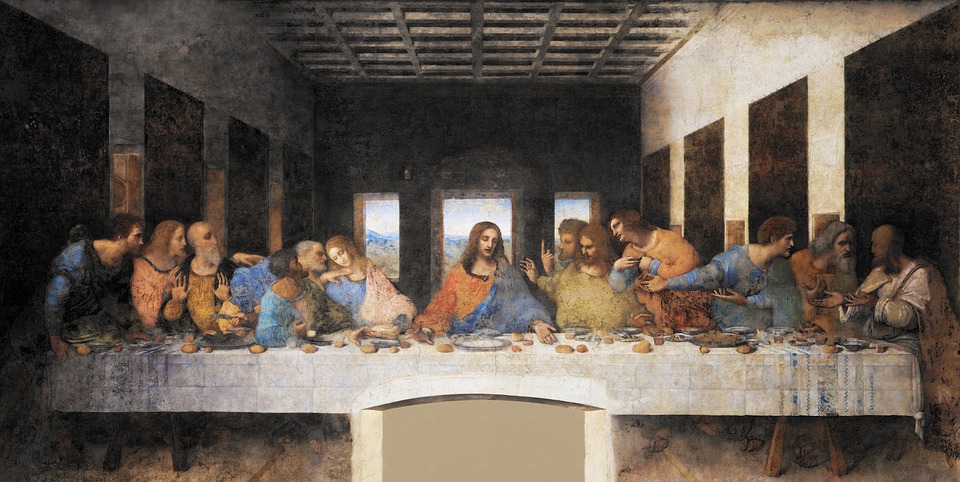

After I finished the book, I went to peer at the framed picture of Da Vinci’s The Last Supper that hung above the dining table. I wanted to see if I could spot Mary Magdalene amongst Jesus’s Disciples. As soon as I did it, I felt ashamed. By looking at the picture, I had allowed doubt to enter my mind. I went to the confession box and broke down. I must not have been the only one because shortly afterward, my parish organised a lecture where an ‘expert’ methodically took apart the claims of the book.In attendance were a frazzled percentage of the congregation: good, decent people who had respectable marital sex and raised chaste daughters and honourable sons.

All these years later, I have no memory of whether I left that lecture with any answers. Memories are shape shifters, fluid and untrustworthy, continuously producing new meanings as we grow and learn.My memory of being a teenager in Gujarat is tied up with indelible images that snap into sharp focus. A man being beaten on my street, the slap of his slippers on tar as he runs, the stomach-dropping sound of hard staffs hitting flesh.The blackened walls of Muslim-owned shoe shops in the bazaar torched by mobs during the night. The long, silent lines for milk and bread after curfew lifted. Looking back now, I have no doubt that these images prompted me to be more Catholic than I felt sometimes. I didn’t allow myself to engage with Faith in a way that felt personal to me. I performed Faith, as I had been told to, never entertaining alternate interpretations of it. Faith was a part of my social identity but it was also a part of my spiritual life. I was by no means a “Holy Joe” and I was the first one to roll my eyes with my friends at a too-long sermon or a boring Catechism class. However, when I re-read my journal from 2003, I am surprised at how many entries ended with prayers or invoked God in some way.

It has been some years now that I have walked away from institutional religion. The break happened in those blessed years when I was deciding who I was, what my politics were and what my values were. My politics– being pro-choice, being an ally to queer communities, being feminist – didn’t align with the official position of the Church. I started to feel uncomfortable around Christians in general, seeing the deep divides of class and caste at Mass or during festivals. I started finding more Sunday Mass sermons oppressive, irked by the sanctimonious air of the clergy,the often regressive interpretation of the readings and the preachiness disguised as counsel. I stopped going to Church altogether. I decided not to raise my son Catholic.

Yet, unlike my partner, who was raised Christian but is now an atheist, I can never fully shake my Faith. I pray, sometimes by writing, other times using traditional Catholic prayers that I learned as a child. I can easily rattle off a million reasons why organised religion is horrible to women, minorities and LGBTQIA communities, how many times it is realised in violence and bloodshed. Yet, a faith born of organised religion has been my comfort in grief and my anchor in uncertainty. It has put a spotlight on the precious, tiny, tender things about being myself that I tend to overlook when I’m insecure, unsure and overwhelmed. When I see this world careening into what looks like a dark abyss, Faith tells me to hope and keep going.

Which brings me full circle I suppose, to The Da Vinci Code. I dug the book out recently to see if I could discover what about it shocked me when I first cracked it open. I expected to have a good laugh at the expense of my prim 15-year-old virginal self. The book, speaking for its literary qualities alone, is not to my taste at all. Yet, one theme in particular jumped out at me – the move by the characters to reclaim the narrative of sex from its conservative underpinnings. This was more in line with the way I experience sex. Was I, Heaven Forbid, finding affirmation and wisdom in a Dan Brown novel? That did make me laugh. Thanks, Mr. Brown.Ultimately, I realised that it was the positioning of the Vatican and the Church as the villains that actually made me so uncomfortable all those years ago. An author who didn’t know me and my context, didn’t know the circumstances of my life,was telling me that the things that gave my life structure and meaning were the result of centuries of manipulation and deliberation.I suspect that it was this, rather than Jesus having sex, that made me cry in that confession box and attend that lecture. Perhaps I wanted answers, but perhaps I wanted reassurance more. I am able to be kinder to my 15-year-old self when I think of this.

In my adulthood, I have experienced God outside of how I was taught to experience Him. I have discovered that I am a sexual being with infinite ways of experiencing pleasure. Almost all of these ways are outside of the tame abstinence-penetrative sex to get pregnant-abstinence cycle prescribed by the Catholic Church. Once I’d thrown away the rule-book has been an exhilarating part of my twenties, sort of like striking out to sea without a boat in sight. The waves are difficult, they may even consume me, but they can also be gentle, a cradle, a song of salt and sweetness. How very odd that this beautiful journey began with a scandalous, pulpy best-seller and the image of a kissing Jesus.

Cover Image: Pixabay