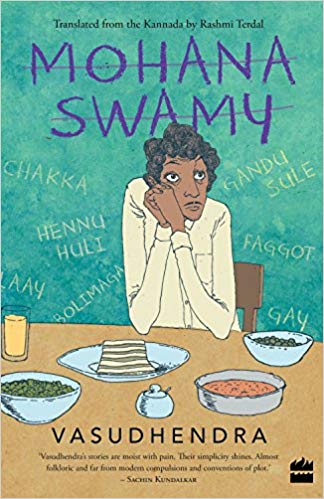

Mohanaswamy by Vasudhendra translated by Rashmi Terdal (Harper Perennial, 2016)

Nissim Ezekiel’s sacrificial mother and the scientific, rational father in the Night of the Scorpion from our school textbooks, the image of Bond’s The Woman on Platform 8 and the refrain of Sarojini Naidu’s Palanquin Bearers came flashing to my mind, as I wondered why, amid the worlds we traversed reading literature in all my years as a student, I hadn’t come across a narrative like Mohanaswamy in our education. For in reading Mohanaswamy, a personal account of the protagonist’s different spheres and times in life, one gets an insightful glimpse into the different ways society interacts with (and discriminates against) anyone not feeding its stringent reproductive order. The book, educative yet a fluid read, with its multi-faceted slice-of-life stories, strung together through the protagonist’s experiences, traversing different cultural spaces, the rural and the urban, brings to light so much about humanity and the rigidity of “masculinity”.

The author pens the life of Mohanaswamy, a homosexual Brahmin man raised in Ballari village in Karnataka and lucidly takes the reader through his childhood, adolescence, youth and adulthood, taking them along his varied journeys, revealing his inherent traits and how his experiences and his learnings from them shaped his perspectives and his choices.

The reader progresses, through Mohana’s own narrative, from gossip leaving deep imprints on his self-perception to eventually him seeing, with his own eyes, those perceptions being shattered. Upon hearing from friends rumours that progeny may be “gay” if women are on top during intercourse, or if the man fathering the child is old, Mohana is deeply perturbed and curses his parents and his fate, and his relief is shared by the reader as this belief is dismantled upon finding that a cookie-cutter straight friend has an older father. Mohana’s journey and development towards self-acceptance, as an individual and with regard to his sexuality, is poignantly woven through the different anecdotes.

These anecdotes bring out the depth of the everyday. It is through mundane, universal experiences that the author draws attention to the social checks and balances that guide individual decisions and shape self-esteem, and how they disproportionately impact the marginalised. Underlining this, the chapters thought provokingly touch upon numerous social “givens”, such as the social perception of education as symbolic of “good” character, on ‘respectable’ career choices, on the determinants of male bonding, friendships, attraction and the homophobia therein, of marriage as an exclusionary institution (legitimising certain forms of love and being a gateway to social acceptance for some but not others), the power of silence and invisibilisation, and the strength that comes from self-acceptance. For instance, where Mohana loses social acceptance in certain spaces on account of his sexuality, he gains respect and social validation through his career choice as an engineer. Through Mohana, who is standing at the cross-points of such norms, the reader is compelled to reflect on the scale and magnitude of social norms that define the boundaries of masculinity.

The role of shaming in the construction of masculinity, and its impact on the confidence and ability of the protagonist to open himself up and grow, especially in his formative years, has been beautifully brought out. The importance of positioning (who, where and in what context) for a child is notable. Mohana could still bear it when his sister and peers would call him “gandusule,” a profanity, but Mohana’s world was shattered when, in anger and frustration, his mother called him out for being gay. Similarly,the reader can see, how shaming affected Mohana’s participating in or refraining from household chores like cooking and cleaning, and pleasurable expressions such as dancing and singing, in turn adversely affecting his self-confidence, particularly in adolescence.

The book is especially remarkable for readers of both Indian English and Kannada literature, for amplifying the voice of sexual minorities in Indian towns and villages. Mohana’s joyful discovery of two foreign men unabashedly making love in a temple in Hampi, gave him comfort and strength in the knowledge that he was not alone, that homosexuality is not something to be ashamed of or corrected (the reason he went to the temple in the first place). Through its vivid and raw depictions of socio-cultural life in rural Karnataka, the author, Vasudhendra, a key voice in contemporary Kannada literature, brings forth his identity in all its intersecting dimensions, through the inclusion of class, caste, religion, gender, rural-urban location, education and language. He thus provides a nuanced addition to the literature on sexual minorities in India, as well as globally, in a discourse largely dominated by the voices of and for the urban, educated, interconnected and globalised community.

The book ends on an exhilarating and positive note with Mohana’s ascent to Mount Kilimanjaro, a metaphor on climbing the challenging mountain of life and enjoying one’s achievements, while also contextualising one’s struggles and successes in the vastness of the universe.

Cover Image: Amazon

To read this article in Hindi, please click here.