Very often after watching movies that fall under the somewhat capacious genre of feel-good cinema (mostly romance), I come away a little more disappointed with the universe of filmmaking. The genre deals with sexual intrigue, sex, romance, love, and marriage, and yet, instead of bringing these many building blocks together to explore the many possibilities that each of these elements are pregnant with, the entire genre seems to be a never-ending repertoire of the same story. Characters change from movie to movie, but at the end of the day, boy meets girl and they inch slowly towards the same horizon: marriage. Love and sex are stops somewhere between ‘meet’ and ‘marriage’. But ultimately, the progression from boy-meets-girl to marriage is so linear that it is possible to come up with a ‘formula’ for this genre: it tells the story of (heterosexual) people heading towards a (heteronormative) committed relationship called marriage.

So formulaic is this genre that is has flattened two discourses – marriage and sexuality – in the process of reifying this linear progression towards marriage. It feels as if all sexual exploration begins with one goal: finding a life partner, and ends at one destination: marrying that life partner. In fact, so tied are we to this formula that not reaching this goal is often discussed in terms of a ‘failure’. Sexuality, therefore, is discussed in very finite terms, and marriage is used to police the ‘appropriateness’ of sexuality. In the kindest movies of the genre, ‘love’ fails, and so the protagonists don’t have to shoulder the blame. In some of the more cruel movies in the genre, people learn that their past – often ‘careless’ sexual exploration – has caught up with them to spoil their chances at this other more precious thing: ‘marriage’. This is where the ‘vamp’ ‘fails’ and the ‘heroine’ succeeds. This is how we draw the boundary between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ men and women.

One might say ‘liberal’ movies are different. Different, yes; but better? Not really. They adhere to this formula too, but less harshly. I grew up watching movies like Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994) and Notting Hill (1999) feeling glad that the protagonists had ‘weird’ friends with imperfect bodies, non-heteronormative sexual lives, but also feeling marginal in my own life for identifying with these ‘secondary’ characters and not the picture-perfect, heterosexual protagonists themselves.

So, even if the ‘liberal’ romance, unlike its conservative cousin, ropes in ‘alternative’ sexualities, it ropes it in only as the ‘alternative’. Always an alterity. If it ropes it in as anything other than an alterity, we call the cinema “art cinema”, and not just “cinema.” Of late, we have been flooded with movies where the protagonists themselves explore other possibilities – sex for fun (take No Strings Attached, 2011), short-term relationships (take Ae Dil Hai Muskhil, 2016), same-sex encounters (take 500 Days of Summer, 2009). But, mostly, these experiences are used to establish how ‘cool’ and ‘progressive’ the characters are. After making this point, the movie inches predictably towards the only ‘natural’ conclusion it can imagine for its protagonists: (often heterosexual) marriage.

I won’t say complex mainstream movies don’t ever come along. They do, and across languages and movie industries: Queen (2013), Piku (2015), and Chocolat (2000). Or Amélie (2001), Aranyer Din Ratri (1970), and Apoorva Rangangal (1975). That’s to name titles that popped into my head in random order as I thought of movies that ignore the ‘linear progression’ from sexual exploration to marriage.

But since the mainstream, formulaic film still dominates the screen, I’ve recently started to take subplots more seriously. This is where the non-normative friends exist, and this is where the movie intentionally or unintentionally offers a much better and more intriguing commentary on marriage and sexuality. In this article, I am reviewing three films (or the subplots of three films) to see how subplots show that marriage isn’t a destination or a single story that begins and ends in the ‘happily ever after’. It is a complex social system that is entangled with sexuality, but separable from it. In that sense, sexuality spills across marriage, and is even shaped by it, but isn’t necessarily determined by the discourse of marriage.

I don’t really care for the main plot of this film at all. Mani Ratnam sets out to show you he can make ‘cool’ movies about ‘young’ people; and, so, ‘young’ and ‘cool’ as they are, his protagonists move in together before they get married. And that is all there is to this story. They offer you a commentary on how they don’t want marriage until, suddenly, they do. A linear narrative, disguised as a non-linear one, that ends in marriage.

But in the midst of all this is another story that quite clearly says that marriage isn’t an end at all: two older people – played eloquently by actors Prakash Raj and Leela Samson – rediscover each other and the shape of their marriage in light of the fact that she has Alzheimer’s disease and he has to become her caretaker. The entire discourse on marriage – how they manage disease, share their home with two strangers, and handle guests at home – isn’t wrapped up around issues of sexuality; and all their issues of sexuality – she enjoys dressing up, singing songs of love addressed to no one in particular, traveling by herself in the city, and talking about their courtship and about sex – aren’t wrapped around issues of marriage. Marriage and sexuality become two intersecting and fascinating discourses with infinite possibilities, only some of which are connected to each other. This ‘secondary’ narrative could have been a much better movie than the one about the ‘cool’, ‘young’ people. However, it appears that not only is the director unaware of this potential, he also decides to pit the two stories against each other. He uses the complex marriage of the older couple to make the first couple – who until then, don’t believe you need to be married to have a good relationship – desire love’s ‘natural’ conclusion: marriage.

As I left the movie theatre I couldn’t help wondering why the two stories couldn’t have had a more non-hegemonic relationship: why couldn’t one couple have split up, while the other one stayed together. In making this second story a normalising discourse, did the director not take away from the complex commentary of the two plots in their capacity as separate narratives on sexual agency?

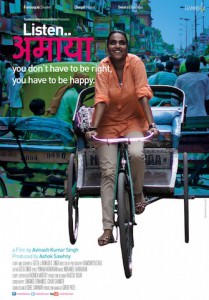

Seen through normative lenses, this movie is quite banal: an older couple (played by Deepti Naval and Farooq Sheikh) wants to get married. Amaya, Naval’s daughter (played by Swara Bhaskar), does not approve. The movie spins a tale around Amaya’s double standards: Is this ‘cool,’ ‘liberal’ woman actually very traditional and conservative when it comes to her mother? On the surface, that is exactly what the movie says. She is a Hamlet: she glorifies her late father and vilifies her mother for having such a thing as sexuality at her age.

But, then there is the sub-plot: minor details that unfold in the backdrop. There is the watchmaker in the bazaar who reminds everyone that time is a social construct: there is no ‘right time’ for exploring the possibilities in one’s life. There are all those good memories of their first marriages that propel – rather than deter – Naval and Sheikh into a second marriage. There is (once again) dementia reminding them that this second marriage comes with its own complexity. There are commentaries on age, friendship, and parenting that populate the movie’s otherwise linear narrative.

Initially, these secondary plots felt so disconnected from the primary one (the one about Amaya’s discomfort and double standards) that I worried that director Avinash Singh wasn’t even aware of their richness. But I was glad to see he was. After seeming like an ordinary commentary on the ‘modern woman’, the story stops using Amaya and her mother as yardsticks to measure performances of sexuality at the intersection of age and gender. Instead, the plot grows richer. Amaya stops playing Hamlet. She looks at herself and her mother for what they are: two women with desires, aspirations and sexual agency, only some of which one will fully understand about the other. Their stories become parallel narratives, not competing, oppositional ones. By opening itself up to such complexity, the movie expands the commentary both on sexuality and on marriage. In the end, the movie becomes more about Amaya getting over her double standards and opening up to her own life’s many possibilities, and to her own flaws.

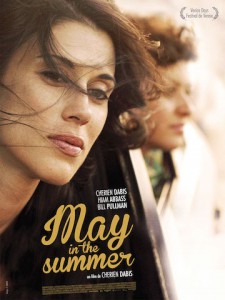

This film is set in Jordon. May, played by Cherien Dabis (also the director and writer), comes back to Amman to get married to her Muslim fiancé, of whom her Christian mother does not approve. The more her mother disapproves of his religion, the more stubborn May feels about getting married to him. However, underlying what seems like another obvious progression from love to marriage is another story: May wants to get married just to disobey her very conservative mother.

At this point, the story becomes two narratives. One explores why May is angry with her mother and why her mother is so severe on a daughter she loves dearly. The other one shows May speaking to a fiancé she loves but is not attracted to anymore. In telling the story of May the daughter, alongside (rather than opposed to) May the fiancé, this movie allows you to reflect on how the ‘natural’ climax of love in marriage can seem both justified and dissatisfying at the same time.

In the end, when May decides not to marry, and May’s mother decides to try dating again, you see that the encounter with a marriage allowed the women to reflect on what they want sexually. Marriage is tied here to sexuality in that it works as a sounding board, not as its only possible outcome.

*

Most movies offer at least two plots, and while some might use them prudently, others may fall short. I guess it is for us to find and relish them even as we wait and push for more complex narratives of marriage. After all, of what use is the ‘and’ in marriage and sexuality if we cannot delink them to see that sexuality and marriage are two discourses – intertwined, intersecting, and interdependent, but not inseparable. They are each vast discourses, limitless in themselves.

When movies don’t pit their plots against each other, we have the opportunity to see how different characters choose differently from each other. It is when these plots are pitted against each other, as they are in O Kadhal Kanmani, that we are left feeling the burn of normative narratives policing other, less normative ones. Otherwise, all these are narratives that exist side by side, with no one possible conclusion, and only infinite possibilities.

This article was part of our March 2017 issue, Marriage and Sexuality, and was originally published here.

Cover still from Listen… Amaya (2013)