It was the summer of 2017. Five years into my Jazz dance training – a dance form that had shaped, moulded and transformed my body and the way I moved. It was an annual dance-off and I was performing a lyrical Jazz piece. Before leaping into the routine, I stood in the ‘Pose’– a pose that had become my moment before starting any routine. It was like bringing the world to a standstill.

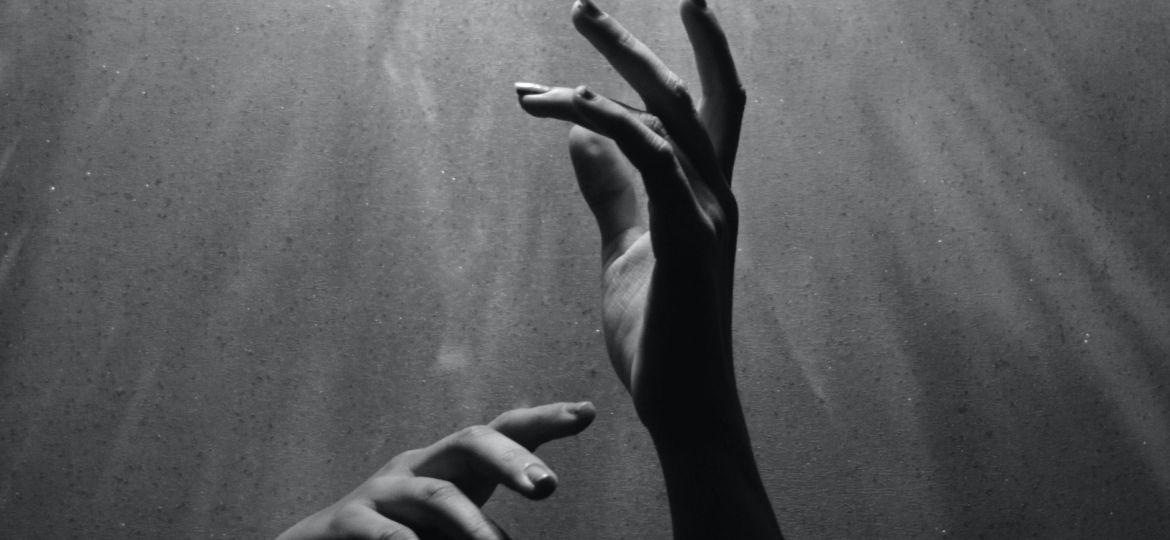

Standing with my weight on the left leg, dropping the right hip and bending the left knee. The base of my left palm rested on the back of the left hip. My right leg extended sideways, toes pointed, and my right arm stretched along the right leg with a drop in the right shoulder. With my chin up, I looked straight at the audience. Maybe not the audience, but I looked all the way to the end of the room. Something about this pose brought about a sense of owning my body, my persona, my expression, my sensuality, my whole being. The drop of the hip made the bottom vertebrae curve, and appear out of alignment from the rest of my spine. A deviance, defiance of the normal straight stance. A resistance, a revolt of sorts.

Many years since, I have been examining the Pose and thinking about how it became an expression of my sexuality. From where and from whom was I drawing this meaning? Is it a personal symbol or do other dancers like me experience this defiance and this way of owning and inhabiting the body, and all that it holds? Does this symbol have an archetypal history? What is the narrative behind the Pose?

While reading Devdutt Patnaik’s Shikhandi: And Other Tales They Don’t Tell You (2014), a collection of Hindu mythological queer stories from the Puranas, the tale of Mohini, the enchantress, piqued my curiosity and wonder. The myth is about how Vishnu transformed into Mohini to help Shiva from Bhasma-asura, a demon. Bhasma-asura had won Shiva’s blessing with his devotion and was granted the power to burn down to ashes anyone whose head he placed his hands on. He tries to use this power on Shiva, and out of fear Shiva flees and approaches Vishnu for help. Vishnu transforms into the enchanting Mohini and appears in front of Bhasma-asura. On seeing her, Bhasma-asura is filled with lust and he asks her to marry him. Mohini says that she would marry him only if Bhasma-asura would dance like her. He agrees and begins to mirror Mohini’s moves. During this seductive play Mohini touches her head with her palm, and Bhasma-asura, forgetting the consequence, does the same and is reduced to ashes.

One of the inferences I draw from this myth is the power dynamic that exists between the performers and the gaze directed toward them. Bhasma-asura, having received Shiva’s blessing, was probably the most powerful demon at that time. So powerful that even Shiva had to flee from him. And only Vishnu, who transforms into Mohini could defeat this demon. Vishnu, in the form of Mohini, beguiles Bhasma-asura and cleverly uses the power she holds over him to destroy him. So fascinated was I with Mohini, that I ran a quick search on Google for images of paintings and sculptures of her. I came across this image and what do I see? The Pose! The dropped hip on one side, the dropped shoulders and the tilted head. There was a sense of familiarity that I found with this pose. The pose depicted here is seen in many ancient art depictions of female bodies. The pose is called the ‘Tribhanga’ or the equipoised stance bent in three places (knees, hips and neck & shoulders).

The Tribhanga also appears in Odissi dance, and is one of the five bhangas (stances/poses); Tribhanga and Abhanga being the most popular stances depicted in ancient Indian art forms. Not only does the pose appear on female bodies/feminine avatars of male gods, it is also used while depicting Krishna lifting Govardhan in the Tribhanga pose, and Natraj, the dancing Shiva, in the Atibhanga pose. We also know of the Dancing Girl of Mohenjo-daro in the Abhanga pose.

In the 21st century, we see the appearance of similar poses in ramp walks and celebrities posing for camera. More significantly, they appear in street-style dance forms that have emerged as a form of resistance. Waacking/Punking has its origins in the LGBT club scenes from 1970s North America and uses many of the bending at the hip, shoulder and knee poses.

With Jazz, heels, waacking and many of the Western forms of dance finding their way to India, I was fortunate, or I might as well say destined, to find my expression in Jazz. My training was technical and stylistic and the instructors were always guiding students like me to find inspiration for the styles. One such example was ‘Cell block tango’ from the movie Chicago. It’s a sequence featuring five female prisoners, who are not the protagonists of the film, but are the leads in the song. It’s stunning, powerful and absolutely captivating! While the five characters are strongly narrated in the song, it is their performance, the poses, the attitude and the moves that accentuate their strength and power.

In the last decade, artists such as Yannis Marshall have been able to popularise these forms of expression and have paved the way for acceptance of gender-neutral bodies and dancing. Even Indian artists like En Lai are changing narratives of sexuality with their art.

The poses and forms of expression, the bhangas, keep appearing in different forms and ways over generations. What narratives do the depictions of ancient and mythological bodies and the poses we see today symbolise? The archetype of the pose speaks of an empowered body. A body that is free from a heteronormative definition and narrative. The pose blurs the binary and speaks of bodies that own their stories, their power, their sensuality and sexuality. It is a way of defying the patriarchal heteronormative narratives that have caged bodies in shame and guilt over centuries. The reappearance of the poses is a motif symbolising the act of owning your authentic self, and defying the culture of shame.

In my early years as a dance trainee, the first thing I learned was the Jazz walk. We would walk from one end of the studio, reach the mirror at the other end, and pose. I remember being very shy and very aware of a gaze which I probably imagined. A gaze that shamed me, my body, my expression. From where had I picked up this shame? It is the cultural narrative that shames a body for expressing its desires and power. We are held back from wholly being ourselves by this shame. To retrieve my true autonomy, I had to silence the shame. While I still struggle with it, I know I have had moments of experiencing the freedom to be, be it only for an hour and a half in the dance studio.