On October 1, 2024, the TARSHI team took a trip to gFest for its Gurugram edition which was held at Museo Camera from September 20 to October 6, 2024. This is a travelling festival organised by reFrame with multiple editions held across different cities in India that invites “diverse sets of people to celebrate, interrogate, engage and contemplate with multiple complexities related to gender through artworks created under its genDeralities fellowships.” This exhibition covered themes such as gender roles and division of labour, migration and belonging, disability and queerness, and the lived experiences of women artists.

Here’s what some of our team members came away with after spending a few invigorating hours there.

TG

A large black banner with white text on it stood out to me at the very outset “First, second and third genders aren’t just numbers; they tell us who counts” echoing the thoughts behind the discussions we have in our sessions and trainings on language and its relevance when talking about rights and experiences of marginalised persons.

Amongst the installations, the one that resonated with me the most was a poem written by Fatima Juned based on their conversations with Muqaish (metallic embroidery) artisans from Lucknow entitled “Mera jahaan kaisa ho?” (What should my world be like?) It was a part of the artist’s larger project “Taaro’n ke Darmeyan” (In the midst of stars). I was pleasantly surprised to learn that the poem was a creatively strung together compilation of the words of the artisans themselves. In it, the women speak about a world that they dream of where work is not a compulsion, where their daughters can access education, where they have a home to call their own. The artwork and poem shed light on the gendered nature of the work of Muqaish artists. While persons of all genders are engaged in this work, for women artisans of Muqaish, their identity as women takes social precedence over their identity as an artist. Their work is often seen as secondary, as something women partake in as a hobby. This in turn means that their labour goes unseen. As the artisans share, “Mera jahaan kuch aisa ho jismein, Meri mehnat ka jayaz sila mile, Meri mehnat ko saraha aur pehchana jaye” (My world should be one where my efforts are appropriately rewarded, appreciated, and recognised).

AK

Visiting reFrame’s gFest was a profoundly enriching experience, and it was fascinating to see how visual representation serves as a powerful expressive tool, framing our perspectives on critical issues like gender, sexuality, disability, patriarchy, discrimination, and oppression.

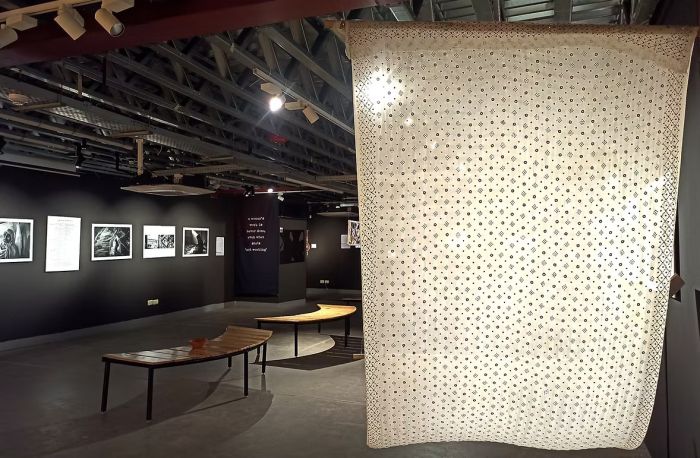

One installation that particularly struck me was “What’s Behind the Window?” This compelling piece showcased Garadu art and narratives that have, over the years, slowly begun to fade from view. According to the reframe website: “Garadu is a woolen garment traditionally made at home, especially by the women of the pastoral Gaddi people, belonging to the Dhauladhar foothills in Himachal. Crafted in different forms and shapes and coming to several uses, it has many diverse names and types – gardi, pattu, chadar, langha, etc., carrying in them collective and individual histories.” The installation was conceptualised brilliantly by Dhaarchidi Collective, named after the Himalayan Sparrow in Pahadi language, which is a group of young women living in the Himalayas. It featured a blanket embroidered with 12 window openings, each revealing a different facet of societal realities. The images poignantly depicted pressing issues such as the unequal division of labour, body shaming of girls, the silenced conversations surrounding domestic violence, sex-selective abortion, the objectification of women, and the stigma around menstruation.

This installation powerfully illustrated how traditional art forms often become obscured as capitalism dominates cultural narratives. In a parallel manner, it underscored how the stories of women and girls from marginalised communities are frequently overlooked, rendering their voices, experiences, and stories unacknowledged and silenced.

NJ

As someone working in communications and looking at gender and sexuality, one is always trying to find appropriate avenues to make conversations on these topics less jargon-heavy and more relatable to everyone’s day-to-day experiences (and oh what a struggle this is! *sighs*). Discussions straddling gender, feminism and sexuality are complex and interwoven with multiple realities. How can one do justice to them? This is a question I often ask myself when creating content.

However, when I attended the gFest, I was impressed to see how simple yet powerful the messaging around gender and sexuality was within every installation. Then it struck me – it’s the art of storytelling! The artworks showcasing the life of someone with a chronic illness, the poems depicting stories of women who do care work, the illustrated dialogue boxes, the chaddar (bedsheets) displaying the hopes and dreams of women labourers, all of them have one thing in common: they are the real and unheard stories that somehow do not find a place in the mainstream platforms we consume. gFest helped me understand how stories are one of the most powerful mediums to connect with the experiences and realities of those one may never meet.

VV

The gFest exhibition had this quote near the entrance: “Gender, sexuality, religion, caste, class and disability aren’t kind enough to hold us back one at a time.” This was a wonderful way of explaining the concept of ‘intersectionality’ in simple language. I thought the installations on women and their various forms of labour, often invisibilised, particularly showcased intersectionality well.

Fatima Juned’s installation features women whose identities as Muqaish craftspersons never come to the fore but who are only seen as “housewives” whose embroidery work is a “hobby”, something to do when they’re “bored”, even when that work brings in additional income for the household. Chandni Ganesh’s installation documents the labour of women relatives of incarcerated Indian men in the UAE. These women, whose visas are often tied to the men’s, take care of the family and do the gruelling, unending work required to try to bring the men out of jail; difficult anywhere, all the more in a foreign country where the odds are stacked against one. In Dhaarchidi Collective’s installation, women from the Gaddi community in Himachal Pradesh use the medium of a woollen blanket that’s a specialty of their region, to raise questions on what’s considered “work”, why their roles in weaving these blankets are not visibilised, and what autonomy women have and don’t. Ipsita Choudhury’s Ghor. Ghar. Home, a beautifully illustrated interactive website, showcases the lives and work of Bengali migrants living in Delhi’s Bhalswa landfill; the women talk about work, water, fish and what brought them to Delhi and what they’ve left behind in Bengal. These installations quietly, powerfully reflect the interconnectedness of economics, migration, gender, geopolitics, caste, and disability, with a dose of good-old patriarchy thrown in.

***

Through seven physical and digital installations, a small subset of the projects worked on by fellows across the first four editions of reFrame’s genDeralities fellowship programme, the festival seeks to showcase gender’s complex relationships to other aspects of our lives like sexuality, work, labour, class, power, politics and disability. Each artist and artwork brought a unique flair to these themes while also maintaining a sense of cohesiveness and unity. The festival’s concept note states: “Lives, as we live them, are complex. Which is why we need spaces where we can celebrate the diversities of our beings, acknowledge our varied lived experiences, and open up new possibilities to question and resist.” reFrame through the gFest, has definitely succeeded in creating, with a lot of nuance and care, this space to explore the gendered natures of our lives through art.

Image Credits: The reFrame Team