SUMMARY

On a midsummer afternoon, a pleasant breeze blows across Fateh Sagar Lake. Clear blue waters shimmer in the sun. Small waves lap against the rocks, occasionally breaking the quiet of the place. The Aravallis, made lush green by the monsoon, loom in a distance. Thirty-eight-year-old Kamlesh Kumar Vaishnav sits on the wall that rings the lake, holding his wife Geeta’s hands. His black wheelchair, folded neatly, is parked next to him. They have been coming here for the last eight years, ever since they began dating. It was here that he professed his love for her; here that they decided to marry secretly and here that she broke the news of her pregnancy to him. “This place has a lot of memories,” says Vaishnav.

In Udaipur, a city with white havelis, palaces and forts set amidst hills, where turbaned men sing love ballads to the sound of the iktara on long boat rides, it is difficult not to fall in love. But Vaishnav and Geeta’s love story is unusual. “I first saw her at the hospital,” he says.

Though crippled by polio since childhood, Vaishnav has never let disability come in the way of life. Till Class V, his relatives would drop him to school each day on a cycle. At the age of 11, his family gave him a self-operated wheelchair. “That was independence,” Vaishnav says. In 2006, he began working at Narayan Sewa Sansthan, a charitable organisation that runs hospitals for the disabled and performs surgeries for those afflicted by polio free of cost.

Vaishnav was an attendant at the reception of the Udaipur hospital, preparing discharge papers of the patients. Geeta, who was crippled at the age of one, underwent a corrective surgery for severe polio at the hospital in 2008. “She had been admitted to the ward for a week. Her right leg was plastered. Even in hospital clothes, she looked so beautiful,” Vaishnav says. For the next week, Vaishnav tried to talk to Geeta, but her parents were always around. When she returned to the hospital six months later to have her legs fixed with calipers, they spoke for the first time.

Geeta, who is 10 years younger, lived in Banswara village, 165 km away, but she would travel for four hours in a bus every week to reach Udaipur and meet Vaishnav. “I would lie to my parents that I was going to see a friend or to the hospital for my check-up. We would meet at Fateh Sagar and talk. Other couples would take boat rides and go to Nehru Park (a small island in the middle of the lake). We could not, it was impossible with the wheelchair and calipers. But we were content to be with each other,” she says.

Narayan Sewa Sansthan, set up nearly three decades ago by retired government servant Kailash Agarwal, now 80, to treat patients suffering from polio and cerebral palsy, appears to be an unlikely place for love stories. On a regular day, a vast crowd sits outside the 1,100-bed hospital in Bari, on the outskirts of Udaipur city. They are relatives of patients, who come from as far as Bihar, Punjab and Karnataka for free treatment for their kin. Young men and women in uniform, many of them disabled, stream in and out of the wards that smell of disinfectant and illness. Agarwal’s daughter-in-law, Vandana, the Sansthan’s director, says the youngsters were all patients at the hospital once, who were treated and later employed there — as nurses, ward boys, receptionists, accountants and in other capacities. Those who were not employed had the opportunity to attend classes in sewing, mobile repairing, computers, and other vocational skills.

The institute also encourages young men and women to mingle. “We try to create an atmosphere where it is easy for them to find a life partner. Many of them think of themselves as burdens. This is a place where they meet new people and find a partner, a hamdard who understands them,” Vandana says.

Eleven years ago, they started organising mass weddings when a few patients approached them for “complete rehabilitation”. Some told her they were “lonely” in life. “That is when we thought: why not search partners for them? We started talking to patients and families in the hospital. Slowly, word spread. We do background checks of both the boy and the girl: what kind of people they are, if the boy drinks or smokes, and the family’s social and economic status,” she says.

Many of the alliances are of those who met and fell in love at the hospital.

When couples face objections from the families, volunteers try to counsel the parents. “There have been many instances where we explained to the family that caste does not matter. Most often, love wins,” says Vandana.

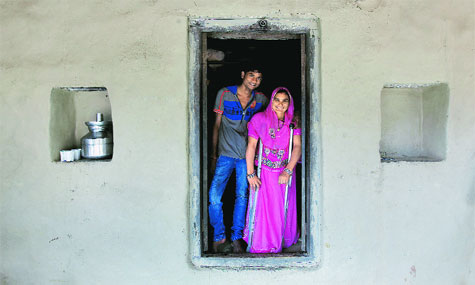

In Juda village, 100 km from Udaipur, residents guide you towards a row of thatched-roof houses near the peepal tree where “langda” lives. Affected by polio when he was one, Manohar Singh was operated at the Udaipur hospital in 2008. At one of the check-ups after his surgery, he saw Mankunwar Kirad, 22, who was operated in 2010. “Our marriage was arranged by the Sansthan,” Singh says. But, later, as his mother steps out to make tea, he hastily adds, covering his mouth with his hand to hide his wide, ear-to-ear grin, “It was the mole under her lip that I lost my heart to.”

The playfulness between them is evident. A few nights ago, while Singh was asleep, Mankunwar painted his hand with henna: his palm is now a deep orange. “We are very different. She is jovial and chatty. I am the quiet type,” he says. The couple married in June this year along with 91 others at a mass wedding at Ramlila Maidan in Delhi.

Pramila Meena and Vijay Singh Chauhan saw each other at the hospital seven years ago. She was a 15-year-old from Dungarpur in Rajasthan, undergoing a corrective surgery for polio. Chauhan was a 19-year-old ward boy, who had been struck by polio when he was two. Even though Pramila kept coming to the hospital for annual check-ups, they spoke only in September last year, when she joined sewing classes organised by the Sansthan.

“I had seen him around and was impressed by his good looks, but never had the courage to talk to him,” says Pramila, now 22. Recalling their first “meeting”, Chauhan says she was in a black salwar suit, with kohl-lined eyes when she stepped inside the hospital: “I really liked her, but how could I talk?” Chauhan spoke to a volunteer and asked for help. “For about a month, she refused to talk as she was scared of a backlash from her family. Eventually, she gave in,” says Chauhan, with a grin.

The way forward was not easy for the young lovers. In a state where caste divisions are stark, the fact that Pramila belongs to the Meena community, while Chauhan is an “upper-caste” Rajput was a big hurdle. Pramila’s family was bitterly opposed to the match. “I was affected by polio when I was just four months old. My parents died soon after. My grandparents raised me. They are old-fashioned and were very unhappy about my wish to marry outside our caste. Moreover, I had been rejected by many suitors because of my disability. So, my grandparents have always been very protective of me. But when they met Vijay, they really liked his politeness. They also realised that he was ready to accept me, even though his disability was far less than mine. I use crutches to walk. His family accepted me whole-heartedly. Eventually, my family also agreed,” Pramila says, when we meet her at her one-room flat near the hospital. They married in June this year.

Vaishnav and Geeta decided to marry in secret after almost two years of courtship. “Had we told our parents about it, we would never have been able to marry. I am a Brahmin and she is from a Scheduled Tribe. We thought our families would have killed us for even thinking about such a match. So, we quietly registered our marriage at the court and continued living at our respective homes. Weekly meetings in Udaipur continued as usual,” he says.

Two years later, when Geeta broke the news of her pregnancy to him, they had to reveal all. “We had no choice. I told my father he could give us any punishment he deemed fit. But he was happy. Neither he nor I had thought I would marry or have a family. For some months, my mother boycotted us. But everyone came around after our son’s birth. He is three now and lives with my parents in Mawli village,” Vaishnav says.

Even though Vaishnav and Geeta were always encouraged by their families to pursue their education, they feel love has completely changed their lives. When he first proposed to her, she says she was surprised. “I had never imagined that I too would be a wife and a mother some day. When he told me about his feelings, I broke down. I had never thought someone could love me. He was frank about his disability, because I walk fine with calipers while he moves around on his wheelchair. But by then, our love had crossed all boundaries. It eclipsed everything else: our age gap, caste barriers, and the difference in the extent of disabilities.”

The love stories have inspired hope in other young patients who come to the hospital. Sukhpal Singh, a 25-year-old with polio, has arrived at the institute from Sangrur in Punjab. He has recently completed his BCA and is about to start looking for a job, but he tells us about battling mocking stares all his life. His mother, Labh Kaur, recalls how someone from their village was operated at the institute, and encouraged Sukhpal to “give it a try”.

As she hears the stories of love marriages arranged at the hospital, Kaur says, “I do not know what destiny has planned. But if those couples found love, surely my son will find a partner too. If he likes a girl here, I will agree. Even if she is not a Punjabi.”

This article was originally published in The Indian Express on August 10, 2014.