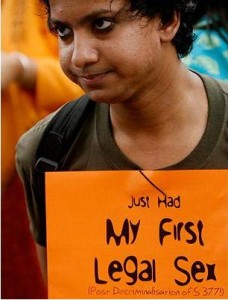

Post the historic Naz Foundation judgment of the Delhi High Court in July 2009, a prominent English news magazine carried a photograph my friend and activist Anindya Hajra celebrating the decision carrying a placard which read: ‘Just had my first legal sex.’ Needless to say, the placard was being displayed with specific regard to a particular kind of sex – that the law, until then had deemed ‘against the order of nature’ – which was liberated from the violent clutches of colonial criminal law after a sustained legal battle.

While this assertion felt like a most obvious one given the significance of the moment, in hindsight it has made me wonder: what is special about sex when it is legal? What does the label of legality do to sex? Does the quality of an orgasm get any better when we have legally sanctioned sex? What was sex like before it was granted legal imprimatur? Has sex reverted to its earlier illegal avatar post the dismissal of the Naz judgment by the Supreme Court of India in December 2013? Why is law accorded such a pivotal role in marking historical signposts in the struggles for sexual justice?

Both moments of celebration and mourning in sexual rights movements the world over seem to be framed by an encounter with the law. Over the past decade or so legal developments have marked the recognition of sexual rights globally. Sample this brief selection of decriminalisation of anti-sodomy laws within national jurisdictions: the Lawrence and Garner case in the US (2003), the Fourie case in South Africa (2005), and two historic judgments from South Asia: the Blue Diamond Society case in Nepal (2008), the Naz Foundation case in India (2009). There have been other celebratory moments too: the Supreme Court of Canada’s decriminalisation of sex work in the Bedford decision (2013), to the passage of the new Criminal Law (Amendment) Act in India (2013), to the Philippine Supreme Court’s decision upholding free access to contraception (2014), to the Norrie judgment of the Australian High Court recognising that ‘sex’ is not restricted to the binaries of ‘male’ and ‘female’ (2014), to the most recent decision of the Indian Supreme Court in the NALSA judgment recognising the ‘third gender’ (2014). These achievements in the realm of the law have also been accompanied by failures where law has been instrumentalised to oppress particular sexually marginalised groups: the Koushal judgmentin India (2013) that declared Sec. 377 of the Indian Penal Code constitutional, the Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2014, and the Nigerian Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act, 2013, to the Australian High Court striking down the Marriage Equality (Same Sex) Act in the ACT case(2013), to name a few.

Law’s relationship with sex and sexuality, thus, is at once vexed and intimate. It almost seems impossible to write a history of sex without reference to law. And the same is the case the other way around: some of the landmark cases in legal history, in India or elsewhere, are ones that deal with sex: as identity, act, morals, science, work, politics, performance, religion – you name it. But the relationship is a curious one in which despite law being at the foundation of sexual oppression, it is law that is also appealed to for undoing that very oppression. If particular kinds of sexual desires are criminalised or regulated by law, it is a desire for a legal resolution, or a legal challenge to that criminality, that drives our struggles against sex-phobic laws. The law, in its encounters with sex, is thus an object of both desire and derision. It is medicine and poison at the same time.

This complicated relationship that law and sex share, throws up a set of concerns that ‘we’ cannot not be attentive to in our activist, academic, and quotidian experiences of living sexually, and resisting the hetero-patriarchal order that the law sanctions and normalises. My use of ‘we’ is meant to signify those of us who think and struggle with the law, and not to gloss over the many divergent and opposing positions that inform our thinking. The law works as the most potent flashpoint moment in our struggles for sexual justice in most parts of the world that demand repeal of oppressive laws or enactment of empowering ones. I don’t need to over-emphasise how important these efforts are. However, what remains a concern is the way in which the law gets projected as the singular point where sexual oppression and emancipation meet: one that is at the root of gender and sexuality based marginalisation, and one that is the most potent response to it. Escaping this double bind of the law’s promise of justice and its reality of violence becomes a formidable task for sexual rights struggles. The spectacle works in such a way that legal achievements tend to blind us to their consequences. Can decriminalisation of sodomy be universally emancipatory? Can it not, in fact, be a more insidious mode of surveillance and regulation? Is marriage equality in law a move to assimilate queer people into the folds of hetero-patriarchy? Can the trope of the right to privacy that is used on most occasions to legally challenge anti-sodomy laws become a marker of class privilege? Can the claim to privacy be a depoliticising move that domesticates sexuality? Does legal emancipation ossify sexual identities as fixed and unchangeable? Isn’t the (almost) universal cry for decriminalisation part of a larger politics connected to global governance and aid politics agendas? Haven’t decriminalisation and same sex-marriage rights come to operate as civilisational markers of progress? Can’t anti-sexual assault laws also lead to a sexual sanitisation of public and work spaces?

Despite these important questions, abandoning an engagement with law will be foolhardy. It will mean ceding space to the State, and increasingly the market, to enact and adjudicate who we have sex with, how we have sex, who can be sexually assaulted, and who qualifies as a sexual assailant. It would allow the State to work out ways to conveniently absolve itself of any accountability, both as the entity that needs to proactively work with laws to protect sexual rights, and undo sexual wrongs by repealing laws that criminalise consensual sexual practices. While this is prevalent wisdom that we have learnt from the long history of the women’s movements’ engagements with law reform on sexual violence in India, what we are experiencing today – the concerns exemplified in some of the questions above – is a new politics of oppression where the State and the corporate market work as a sophisticated compact in regulating sex and sexuality. If the State speaks the language of legal rights in its dealings with sex and sexuality, that is where our attention gets fixed. That is what we get most attracted to, given the amount of importance that our struggles invest in the law. This allows for two things to happen: first, it lets the State carry on with its violent tactics of governance, now that it has diverted our attention, under the garb of promises of law reform. Second, the corporate market arouses our desire and seduces us with products and accessories as a gesture towards promoting ‘free choice’ as a right – isn’t that also what we want the law to recognise with regard to sexuality? In the operation of this new politics our desire for sexual rights is informed not only by the Constitutional framework of laws, but also by the laws of the corporate market.

Take for example, the immediate post-Koushal period. In no time, corporate lifestyle brands were out with advertisements in English celebrating same-sex desire. While corporate India’s response can be read as progressive, yet at the same time, its appeal was specifically aimed at a class of queer consumers who can afford these products and aspire to an elite lifestyle. The advertisements were reflective of an atmosphere where only a select few could rejoice in the queer-friendliness of corporate benevolence. Mind you, there were no freebies. These were advertisements to raise sales, smartly packaged in a rainbow wrapper. Similar concerns about elitism have been raised time and again regarding one of the decriminalising planks of the Naz decision: privacy, as a matter of class privilege that many non-elite queer people do not have access to. In the post-Koushal scenario, this elitism seemed to have seamlessly moved between the realm of the law and the market.

While this was happening, in the din of statements by political parties on the Koushal judgment, the then ruling party, Congress, declared that they will support a legislation in parliament to repeal Sec. 377. The Congress party even went on to include this commitment in their election manifesto. Such a commitment by a major political party has been unprecedented, and only goes to show the impact that the anti-377 movement has had on public and political consciousness in India. Of course, this also points at how queers were being considered as a constituency worthy of being of voters (in effect citizens) in the pre-election moment. While the Congress’ move was celebrated by many, I would argue, that it was used as a convenient ploy for the then ruling government to portray itself as progressive, and taking attention away from the fact that it is the same government which has been unleashing brutal violence against India’s adivasi populations, at the behest of corporate interests. The perverse use of the promise of law reform to the sexually marginalised on the one hand, and to carry on legalised violence on peasants and ethnic minorities on the other.

In the light of Narendra Modi’s coming to power, we’ll also be mistaken to write off the BJP as a rabid right wing party which will never support sexual rights, despite its public stand against Sec. 377. If neoliberalism has wholeheartedly been embraced by the Hindu right, it wouldn’t be surprising if, in its acche din aane waale hain (good times are coming) avatar, the BJP starts supporting sexual rights, albeit one which promotes an essentialist version of Indian history that is Hindu, and thus tolerant of sexual diversity. That Hindu culture has been open to homosexuality, but it was only when the Muslim ‘invaders’ plundered India, tolerance for sexual diversity took a plunge, is a narrative that is perfectly compatible with that of the Hindu right. Such an argument, versions of which have been propagated by many right wing queers, allows the Hindu right to Brahminise India’s sexual past through the creation of the evil Muslim homophobic outsider. If this serves their communal nationalism better, the Sangh Parivaar will do this. If this serves their communal interests better, the Sangh Parivaar will do this, as is evident from the RSS spokesperson Ram Madhav’s latest indication of the possibility of a softened stand on Sec. 377.

Poison and medicine. Desire against desire.

While it might be too depressing to say that this is an intractable situation, it is necessary for our struggles to develop imaginations of sexual justice and rights outside of the confines of the vocabulary that the law offers, or reimagine law outside of its state-market captivity. We need to do this even as we continue to challenge a whole gamut of laws – not just Sec. 377 – that criminalise adult consensual sex, or deem adult consent irrelevant: the Immoral Traffic Prevention Act, adultery, marital rape, to name a few. This certainly is easier said than done, and might even sound like hollow romanticism at best, and pure stupidity at worse. Yet, that is possibly the impossible horizon that must inspire sexuality’s (dis)engagement with the law.

Returning to the placard’s assertion: to exclaim the occasion of your inaugural experience of having ‘legal’ sex carries a very powerful symbolic message that might do nothing to make us have better orgasms. But symbols of emancipation are not mere bourgeois vanity, they have real affective consequences. As a South African drag queen commented on the South African constitution’s recognition of sexual orientation in its equality clause: ‘My darling, [the constitution] means sweet motherfucking nothing at all. You can rape me, rob me, what am I going to do when you attack me? Wave the constitution in your face? I’m just a nobody black queen. But you know what? Ever since I heard about that constitution I feel free inside.’

This post was originally published under this month, it is being republished for the anniversary issue.