‘Woman? It’s simple, say the fanciers of simple formulas: she is a womb, an ovary; she is a female – this word is sufficient to define her.’

–Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex

These words were written in 1949. The world has changed the lens with which it views women many times over, mostly because economic growth has necessitated the acknowledgement of female labour, and because feminist forces have constantly fought for the elimination of discrimination against women in their lives and work. Yet, when it comes to reproductive health, I wonder if women are still enmeshed in that simple formula: a womb, an ovary and a bunch of gender roles that affect not only their reproductive experiences, but their entire lives.

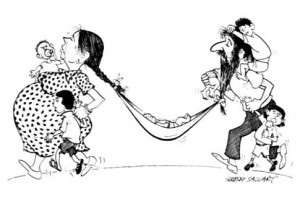

Years later when the cracks in the population and family planning policies became obvious, I was stunned by how well the slogan and the logo masked the gender inequality within patriarchal nuclear families. Using the words, ‘hum’ and ‘humare’ (we and ours) along with a sketch in which the man and the woman look equally in control, the family planning agenda makes it seem as if the two players in this equation are the State and the equally empowered couple. But there are really three players in the equation: the State, the man disempowered by poverty, and the woman disempowered even more by poverty and her gender. In other words, the implementation of the policy is gendered, and it affects the unequally disempowered men and women differently.

In recent times, some of this difference has been deliberate. During the Indian Emergency (1975-77) 8.3 million sterilizations (75% of which were vasectomies) were performed in aggressive camps held in poor districts of the country. When this coercive and exploitative move was rightly criticized, the government launched new agendas that focused on voluntary acceptance of contraception. But around this time the focus shifted to female sterilization, partly because of medical advancements and partly because the acceptance was higher if family planning was integrated into other successful programmes for maternal health. For the state this is a win-win situation. By seeking to provide services for its more compliant female citizens, the state can work both towards meeting public health goals and population targets. Moreover women-centric contraceptives are thought to empower women by allowing them to regulate their fertility and the size of their families without having to depend on their male partner/s to do so, giving the State an opportunity to work against inequity as well.

This new approach could be subversive. It could operate in spite of the unequal power-relations between men and women within their families, and correct gender inequity using the very vehicles patriarchy employs. Motherhood is sacrosanct in a patriarchal society, and earns a lot of respect for women within their homes. Young girls and women receive more attention during menarche, marriage, pregnancy and childbirth. In a way, it is very clever to build programmes that reach out to women and girls around this time, and help them take care of themselves along with their pregnancies and children.

Unfortunately, it’s only subversive in theory. Political, legal, medical and economic systems are riddled with patriarchal values and the programmes they spawn normalize the heterosexual marriage and the patriarchal family that springs from it. The upshot: women in general are still disenfranchised, and women who don’t play by the rules of this game even more. There are plenty of rules about who should get pregnant, when and how, and this choice does not rest as much with the women as one is led to believe. Though the language has swung from coercive family planning to reproductive choice, these choices are still mostly available for married women, who want to start a family; and family of course is still defined the old-fashioned way.

Such conservative discussions around reproductive health acknowledge only very insidiously the act without which there will be no procreation: sex. Sexual health remains separate, elusive and a much greater taboo. In A History of Sexuality, Foucault also writes, “Through the political economy of population there was formed a whole grid of observations regarding sex.” He goes on to explain the transformation of sexual conduct within a marriage into a politico-economic behavior, and the simultaneous marriage of all other forms of sex with ideas of ‘perversion.’ This view creates fissure lines between reproductive and sexual health. Sexual health programmes deal mostly with the problems of this ‘perversion’ while reproductive health programmes deal with the welfare of the family unit and through this unit, the nation.

When extended to pregnancies resulting from ‘transgressions’ outside marriage, reproductive health care is infused with stigma. Sexually active unmarried women who don’t belong within the traditional family have to put up with a lot of nagging about their sexual lives when they seek abortions or advice about contraceptives. Trans-women are often referred to the sexually transmitted diseases department even if they really aren’t seeking advice about STIs. Sex workers who become visible to the state mainly through programmes that seek to prevent the transmission of HIV infections feel unwelcome in family planning clinics. A sex worker choosing to continue her pregnancy, a married woman choosing abortion instead of childbirth, a woman with infertility opting out of treatment, a college student being unapologetic about her sexual life – these scenarios still shock doctors and policy makers. It’s not at all uncommon to run into people who have had to put up with a lot of shaming before they can actually avail of a service they choose.

But not all is well for married women either. A paper in the Reproductive Health Matters Journal entitled, Yes to Abortion, No to Sexual Rights explores the value of family planning services to women who need them not to plan or space their pregnancies, but to prevent or terminate unwanted pregnancies resulting sexual abuse within marriage. Unfortunately, the Indian Penal Code Section 375 does not recognize the right of a woman to say no to her husband. In fact, it contradicts the Child Marriage Act, by choosing to lower the age of consent to 15 for married girls.

But the winds of change might be blowing. The Post-2015 agenda promises to be more progressive and liberal than the development goals that came before it, and feminist organizations around the world are releasing statements demanding action points that could then steer a paradigm shift in economic and social frameworks which affect women’s sexual and reproductive lives. Will this shift force countries to stop viewing women’s fertility as a quick fix to the population issue? Maybe. And maybe women will be able to break free from those simple formulas that force them define their lives around their womb and ovary. Maybe in a few more years, the word female could be an identity not an impediment. But in the meantime, any baby step in that direction of change will be a welcome one.

This post was originally published under this month, it is being republished for the anniversary issue.

Pic Source: Caleidoscope