We don’t have an original I-Column this month. Instead we feature the voices of two women, Deepika Padukone and Reshma Valliappan, sharing their experiences and insights on battling mental illness. While Deepika speaks to a journalist about her experience, Reshma writes Deepika an open letter. Read on.

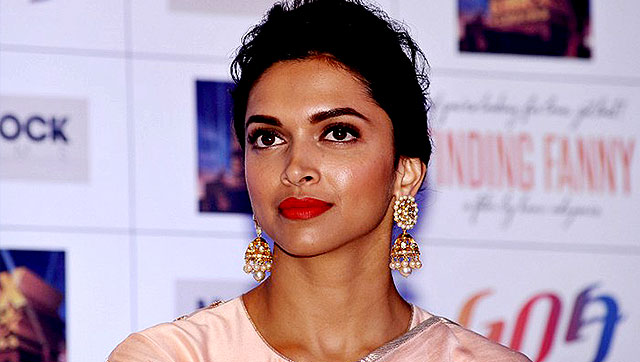

Recently actor and model Deepika Padukon spoke publically about her struggle with depression. In an exclusive interview with Hindustan Times Deepika shares her experience:

In early 2014, while I was being appreciated for my work, one morning, I woke up feeling different. A day earlier, I had fainted due to exhaustion; it was all downhill from there. I felt a strange emptiness in my stomach.

I thought it was stress, so I tried to distract myself by focusing on work, and surrounding myself with people, which helped for a while. But the nagging feeling didn’t go away. My breath was shallow, I suffered from lack of concentration and I broke down often.

Over a period of time, it got worse. When my parents visited, I would put up a brave front because they were worried about me living alone and working long hours.

Then, once, while talking to my mother (Ujjala Padukone), I broke down. She realised the problem, and got in touch with a psychologist friend, Anna Chandy, to get to the root of the cause.

Every morning, it was a struggle to wake up, and shoot for Happy New Year’s (HNY; 2014) climax. Finally, I had a word with Anna aunty. She flew to Mumbai from Bengaluru, and I talked my heart out to her. She concluded that I was suffering from anxiety and depression.

When she suggested I take medication, I was resistant. I thought talking was enough. Later, I met another psychologist, Dr Shyam Bhatt, in Bengaluru for a second opinion.

There were days when I would feel okay, but at times, within a day, there was a roller-coaster of feelings. Finally, I accepted my condition. The counselling helped, but only to an extent. Then, I took medication, and today I am much better.

Most of HNY was shot through this phase. But before starting my next with Shoojit Sircar, I took a two-month break to recover mentally and physically. I spent time with my family in Bengaluru and was soon better. But, when I returned to Mumbai, I heard about a friend committing suicide due to anxiety and depression. It was a huge blow.

My personal experience as well as my friend’s death urged me to take up this issue, which isn’t usually talked about. There is shame and stigma attached to talking about depression. In fact, one in every four people suffer from anxiety and depression.

The World Health Organisation has stated that this will be the most widespread epidemic in the next few years. We talk about all kinds of aliments, but this is probably one of the deadliest mental disorders. Nothing, including life, makes sense to people suffering from it. Overcoming it has made me a stronger person and I now value my life much more. Accepting it and speaking about it has liberated me. I have stopped taking medication, and I hope my example will help people reach out for help.

I feel that at times, the patient just wants to talk, and isn’t seeking advice. But, well-wishers saying things like, ‘Don’t worry, it will all be alright,’ might be detrimental.

Being sad and being depressed are two different things. Also, people going through depression don’t look so, while someone sad will look sad. The most common reaction is, ‘How can you be depressed? You have everything going for you. You are the supposed number one heroine and have a plush home, car, movies… What else do you want?’ It’s not about what you have or don’t have. People talk about physical fitness, but mental health is equally important. I see people suffering, and their families feel a sense of shame about it, which doesn’t help. One needs support and understanding.

I am now working on an initiative to create awareness about anxiety and depression, and help people. My team is working with me to formulate a plan, which will be unveiled soon.

Artist and Author Reshma Valliappan, who published her book Fallen, Standing recently, writes Deepika Padukone an open letter that was first published on NDTV’s website:

Dear Deepika,

Ever since I heard about your coming out of the closet, so to speak, about your struggle with depression, I have wanted to write. I have swung between many personal and political issues concerning mental health since listening to you.

I had to remove your celebrity image in my head and look at you as a human being in order to write this. I’ve self-harmed as a child and continued through adulthood. Often, I have bouts of severe depression where I feel I’m choking for days or weeks, and then, as if with a flip of a coin, I spring up to a high and prance about like the world is mine before I hit a different nerve and drift way into a fantasy land of zombies, ghost and what not. I have my version of depression but that is not what my label is. The one I carry- Schizophrenia- seems to be every Bollywood director’s favourite sell, to the point of having sometimes made a mockery of what someone like me deals with.

The day I came out of the closet, I knew I was going to be even more alone than I already am. As I emerged, I had very few models or mentors who have braved the stigma, and have carried the torch for decades, for people like me. More have begun to join in, and the number of people who feel they can speak out about schizophrenia is slowly growing. This has helped us know that we are not alone with the invisibility of our human condition that is called mental illness. Not alone in the lonely road of existential crises. Not alone as we fight with our caregivers to get them to understand we are people first and not ‘disorders’. Not alone with our own stigma and the stigma we receive from outside ourselves too. When I thought about what it must be for you – all I could do was imagine the world you are in and the one you come from.

As you try to create awareness through your own experience, I write to let you know that you are not alone on this road either, even though in mental health advocacy, the journey is often a lonely one. I also write in to tell you of some of my concerns about how society deals with mental health – so different from other ailments. What many people don’t know is that a person like me has no political or legal rights whatsoever. In the eyes of the law, I may as well be dead. I cannot vote, cannot marry, cannot sign a contract, and I can forget about getting a job.

Most importantly, I do not have the right to choose my own treatment. I can be forced against my will, be dragged into an institution to be locked away forever. I can be given electric shock therapies, have my brain cut open if someone sees fit, I can be raped and abused and the world will not know of me or what I endure. When I say ‘I’, I am not talking only about my individual story, but that of millions of women and men in India who suffer from mental health issues, and what we go through in the name of care.

It is an irony. If I have no rights even after treatment, why bother to get better? How has the system or society benefited me? If I have no say in my treatment and I can be dragged inside on the grounds that I am violent or dangerous – how is it that so many others who commit grave crimes walk free? Most of us have been victims of such acts either outside institutions or within the very walls of psychiatric institutions and facilities that are meant to care for and protect us. Yet, I am the one considered dangerous to society.

I continue being criticized as I fight for what I stand for. I simply ask for what is mine. That I should be seen as equal to everyone else with legal rights. I ask to be treated with dignity and respect, but just yesterday someone told me ‘not all mad people are capable of thinking for themselves. They run away. They live on streets. They can be of harm to themselves or others.’ I have been through all that, but it does not mean I am incapable of thinking.

People like me are incapacitated at many levels. A large number of youth are so diverse in their emotions, thoughts, intelligence, spirituality, but because we have no legal rights, we have often been guinea pigs for the medicalization of human experiences.

There are no biological markers or scans that show mental illness. No way to diagnose it beyond determining whether one is performing all personal, social, filial, professional roles ascribed to us. Society has a set of constructs that one must abide by and if we don’t manage, the diagnosis is quick. To me, depression feels like having access to a range of human emotions that we are otherwise asked not to feel. It tells me that the world is not a beautiful flowery place and I am in touch with these ‘negative’ emotions and that it is okay to do so.

I call my Schizophrenia my experience, invisible to everyone else. I’ve described it as my heart having been broken at many levels, trying to get my attention, so that I listen to myself more carefully. This is what my diagnosis means to me. When I am feeling depressed, I tell myself that a part of me needs to let go. I weep and howl and break. When I am on a high, it allows me to simply love irrespective of any differences that I would have otherwise judged. When I panic, I’ll strip in the comforts of my own room and jump around screaming to music. When I am anxious, I start cleaning my entire house. When I feel nothing, I am nothing. And when I am hyperactive, others tell me ‘Why don’t you take your medication? I ask them ‘Why don’t you take medication to understand me?

I am not dismissing the seriousness of mental health issues, nor am I romanticizing them. Far from it. By no means do I suggest medication is not a part of the solution, I simply want to the choice to take it to be mine, and not have it taken away from me. I don’t want my depression to merely be ‘treated’. I need it to be understood. I don’t want to ‘treat’ myself but I want to be respected as a human being with the choice to say “yes” or “no” to a conventional treatment of medicines and to be given the range of support possible. It is not an ambitious choice. In my personal experience, the system in which treatment exists in India operates on the notion that people like me are outcasts in society. So isn’t it logical to consider alternatives to institutionalized medical care that can at least help part of the way?

I do not expect you to take on our cause alone. I know too well that raising awareness amidst such stigma is an uphill task. But I write to you with the hope that through you, my voice will reach the very world that rejects us, because they accept you – where those who only look at me as a “disorder” will also be able to look at me as a human being.

I write to you for many reasons with pictures I should paint. I write to simply tell you my story, and also to tell you that my story is not unique. I write to say “thank you” for the care and compassion you have brought to speaking about depression and mental health in the open. What we need are listeners. So I write to thank you for speaking, and for listening.

Peace and colour,

Reshma Valliappan