Should it have been a full stop or a question mark that finished the above title? It deeply confused me. And then it hit me. How does it matter? Why am I writing this anyway? Inherent within grammar and punctuation has always been the ability to give meaning and to strip it away, instantly and most often, mercilessly. And it is this power of constructed meaning and plausible interpretation that has always been a source of great excitement and exasperation during my thinking life. How do we read what is written and secondly, do we even read what is written? What is important – the intent with which creativity takes birth or the eventual meaning that it is perceived to hold? We hear very few artists speak. We judge based on whether or not it serves our worldview of ‘shoulds’. And that, is how we imbibe.

***

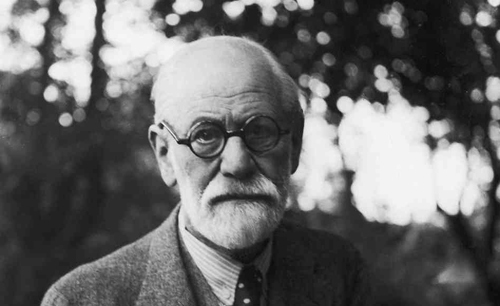

Disclaimer: I love Freud. Or rather, Feminist Freud. Because, he served my purpose.Because he made me a feminist.

The debates on Feminism and Freud have given rise to countless works of literature, art and other creations. Freud has faced the wrath of feminists since, well, always. Credit though, should be given to him for writing that was so misogynistic that just critiquing it helped the feminist worldview. I choose to restrict my understanding in this article, of how Freud was in his own way a feminist, to the oedipal complex and titbits from here and there as they come together to make sense in my head. It is how I chose to look at it, and later, to my surprise, figured that I was not alone. My reading of Juliet Mitchell (and the reading of countless others, I’m sure) reflected a similar perception and gave my thoughts the clarity they were begging for. The downside of being born in this day and age is that everything profound has already been covered, so even if you do have original thoughts, they are inevitably borrowed, so one should not forget to cite the reference!

Freud mostly only worked with women. Some of the most crucial psychoanalytic techniques were discovered when working with women. Women were on his mind. Constantly (‘His mother and everyone else’s’ – has been a popular joke directed at him)! It is also true that his audience was limited. He worked in a very patriarchal era, where women’s psyches were deeply influenced by patriarchal norms. And then we ask, aren’t they everywhere, even to this day? Whether one adheres or questions, man or woman, influenced they are.

Hence, let us begin by looking at the Oedipus complex as a function of Freud’s understanding of this very intertwined (with patriarchy) unconscious superego. So, while he did, in his own way, seek to understand women, how they process and perceive their experiences, the patterns they form and live out, the whys and hows of them, it is crucial to keep in mind that these observations came from a superego predisposed to patriarchy. Considering the era that Freud was living and writing in, we can see that even though his superego was coloured by a patriarchal worldview, he made an effort to dissect what led to that ego and superego formation, for both, man and woman. However, even though at many instances Freud may have disregarded the importance of social and cultural influences, a closer reading of his work seemed to me as symbolic of social and cultural influences. And this journey of Freud to understand women and their reality was for me his first step towards questioning patriarchy and my starting the journey of becoming feminist.

Before we get into that however, it must be briefly mentioned that Freud initially started out to equate masculinity with activity and femininity with passivity. Over the course of his work, however, he realised that these were psychological attributes found in all people, man or woman, and were not directly based on biological sex, but rather on the situation that the child grew up in. ‘Situation’ here could refer to the mother, family, society, the Oedipal complex, or a combination of these as they are inter-related and influence one another. Now looking at the pre-oedipal stage, it is important to note that it is not just the girl who notices a ‘lack’, but rather both boy and girl experience the same shock – the boy of ‘castration’ and the girl of ‘penis envy’. Hence, the oppressive male ideal, affects both men and women. The boy fears being castrated by his father. And the girl desires that which the father has, and she does not.

Children, as we know, are perceptive of the minutest of power dynamics around them. Indeed, the little girl and boy, like Freud said, have seen the ‘big penis’ early on in life. Of patriarchy, of power. “In the boy’s case it is of the father, in the girl’s case of all men,” says Mitchell. She has felt its absence. Not its physical or biological absence, but of that of which she is stripped of by society for not being a man. The girl finds herself “unfairly treated.” It is important here to understand that the ‘unfair treatment’ refers not to the existence of the vagina but the lack of the penis; more importantly what the penis signifies (a superiority which does not exist in and of itself but rather has been bestowed by social and cultural norms). For instance, till the 80s or even the 90s, it was still uncommon for women to take up occupations like those of scientists, engineers, lawyers, etc, in comparison to that of teaching or nursing (for various sociological reasons), which would make the options available to men enviable. The woman’s flight to envy here is for that which has been denied and not because she feels that she is not good enough. Hysteria is no longer prevalent but there are newer crises like eating disorders such as anorexia, underlying which is a self that struggles to become that which is deemed desirable by social patriarchal structures and goes to show the control on women’s bodies and desires even today. Another example is the commonly discussed glass ceiling which can make women feel small and futile for reasons that are unexplained but just seeped in misogyny.

On the other hand, the boy, says Mitchell, is afraid to ‘lose’ this very thing at this stage – not because he will lose his ‘masculinity’ but rather, that he may never achieve it. So, both the girl and boy strive similarly for this superiority. The fear of not being a ‘manly enough’ man in this patriarchal world is not only feared once one assumes the identity of man, but since the very moment that one starts to learn what ‘being a man’ actually signifies and the stakes that are involved. Needless to say, he represses the memory of this struggle (and of his feminine psychological attributes) and starts onto a journey of preserving this seemingly all important ‘assumed masculinity’. Even the thought of losing this makes the consequences seem extremely dire. Set in a Victorian age (and this applies to the patriarchal world even today), it is indeed the fear and want of the power that patriarchy signifies. Freud’s message thus to male patients could be that while it is common to be pressured into assuming a hyper-masculine identity, he urges men towards becoming aware of the oppressive masculine ideal, that is getting in touch with their feminine side which would serve to question normative gender roles and also make a shift in how men understand, relate to and behave with women. This is another way of looking at the contemporary discourse of engaging men and boys in the work towards ending gender inequality.

The problem is not that Freud told us ‘what to do’. The problem is that he highlighted ‘what usually happens’. Whether or not it ‘should’ happen, is something we decide. In psychoanalytic understanding, the child has seen not just the father’s ‘penis’ but also the mother’s ‘vagina’. The perceived lack and fear of ‘castration’, thus sets into both girl and boy after seeing the mother’s genitals. “It represents the absence of the phallus,” and in itself, by its very existence, “asserts the presence of it,” says Mitchell. “Acceptance of the possibility of castration is the boy’s path to normal manhood” (referring to the hyper-masculine route). This shows that the ‘ego formation’ of both man and woman is based on fear of a certain uncertainty of life ahead. A perception of a certain sense of the world and how it would turn out to be for them depending on the choices they make, referring to gender roles here. Whether or not they reach resolution the ‘normal’ way. Whether or not they are able to ‘normally identify’ with the same sex parent. The alternatives to which most certainly are ‘abnormal’ (according to social and cultural sanctions). Freud may have sounded like he was prescribing a ‘normal’ way of growing up, but really what he was explaining was the way in which the ‘shoulds’ of growing up are instead dictated by society. A ‘deviation’, that of homosexuality, bisexuality, of embracing a gender or psychological attribute ‘out of sync’ with the predefined biological sex, etc would lead to discrimination and ridicule.

Freud urges us to reflect on whether or not we can think through the depths of how the psyche is formed. Whether or not we will ever be able to absorb his understanding of how intrinsically internalized gender and gendered notions are. And then, whether or not we will be able to break free from them. He gave us a way out. Of inherent bisexuality. Of women choosing not just to identify with the mother who has accepted the lack as her fate but also as active agents who would decide what worked for them better once they understood the lack that has been forced onto them. Freud talked about fixations. Of failure of the right kind of oedipal resolutions. And he did most of these while working with women. He took the time to understand what it is that women think, experience and go through. How patriarchy shapes and dictates the core of their growing up. And how they, as active agents, explore how to overcome the lack. Perhaps Freud’s ‘incorrect resolution’ was indeed the resolution feminists desired. We can see from some of the above examples of glass ceiling, engaging men and boys,etc, how Freud is still relevant today and how we can use psychoanalytic thinking in our approach to understanding how psychic processes within a sociological and cultural matrix, conform or subvert gender, sexuality and feminism.

Freud, therefore, started the conversation. He made us think about what women were repressing. And it is for us to think of why. Of what caused them shame, guilt and trauma. And we can then uncover why. Albeit as a reaction, but this is what gave birth to a wave of feminist thought. And for this effort, Freud was Feminist. It is this understanding that made me Feminist. Later, I went on to read many, many misogynistic ideas set forth by him. But, what stayed with me was the little girl who recognized power, the possibility that she might not have it like a ‘man’ does, and her desire to change what many would have called her ‘inevitable fate’. She did. And she does.

References:

Mitchell, Juliet (1974). Psychoanalysis and feminism: Freud, Reich, Laing, and Women. New York: Pantheon Books.

Pic Source: Lourdes.edu