HIV remains exceptional in that it carries the seemingly immutable burden of being synonymous with immoral behaviour.

Open and safe conversations on sexual rights and freedoms in the context of both disease and pleasure should have been the method of decoupling HIV from prevailing notions of morality. India’s HIV programme over the past 25 years chose not to do this.

In September 1998, to the utter horror of HIV activists, the Supreme Court of India pronounced the following in a judgement—“AIDS is the product of undisciplined sexual impulse.” It was hearing the case of Mr. “X” v. Hospital “Z”. The appellant Mr. “X” was a person living with HIV whose confidentiality had been breached by hospital “Z”. The appellant sought damages for breach of confidentiality, which had led to his marriage being cancelled, and ostracism by his community.

This judgement, till it was revoked in 2003 after an outcry from activists and lawyers, took away the right of a person living with HIV to marry, found a family and procreate. This was the first time in judicial history anywhere in the world that a court had suspended an individual’s right to (heterosexual) marriage.

The body, a site of uncertainty, vulnerability, connection, and fragile joys, became the site for reconciliation between disgust and compassion, between pleasure and disease, between power and rights.

Even though this judgement was revoked, the idea that the HIV infection was a result of sexual deviance remained firmly rooted in the public imagination.

In May 2003, the then Information and Broadcasting Minister Sushma Swaraj made the politically pragmatic decision to impose a ban on condom advertising on Doordarshan (India’s government founded public service broadcaster).

That HIV is primarily a sexually transmitted condition amplified the existing draconian voices, which conflated ‘immorality’ with condom promotion, and disease with sin.

Sex workers, drug users and persons belonging to sexual minorities were at best considered marginal to mainstream society, and at worst, those in need of reform and rehabilitation.

Only those who claimed to have been infected through blood and blood products were considered ‘innocent victims’—the rest, as it were, ‘deserved’ the damnation. Men came under fire for ‘promiscuity’.

In the midst of all this, the Government of India played along with the US Global AIDS Strategy which announced what the conservative establishment of the day was most happy with—‘Abstain, Be faithful, use Condoms’– the famous ABC strategy. The assumptions of the ABC strategy merit attention.

One, this strategy assumes that adolescents are either sexually inactive and/or can be persuaded to abstain from sexual intercourse till they are married. Of course, sexual minorities who don’t have the option of marriage weren’t considered here. Two, this strategy assumes that partners within a marriage choose to, or can be persuaded to, remain faithful to each other. Three, and the most debilitating of these assumptions, was that women and girls have full control of their abstinence and faithfulness despite the epidemic of gender violence and disempowerment.

The C of the strategy, condoms, were therefore meant for the ‘others’, the vectors of the disease—sex workers, men who have sex with men, and intravenous drug users.

And double quick, this bumped the condom out of the lives of ‘normal’ people.

The condom was desecrated; it got labelled as a tool in the hands of the sexually deviant, the thing that is used by the ‘outsider’, to be used in hiding.

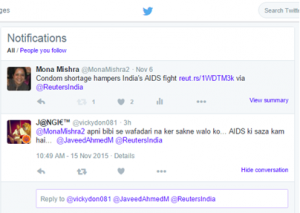

The Twitter exchange below illustrates the issue beyond any doubt.

(The response to Mona’s Tweet translates as, “To those who cannot be faithful to their wife, AIDS is too little a punishment.”)

Remember, the three ‘high-risk groups’ mentioned above (sex workers, men who have sex with men, and intravenous drug users) continue to be governed by laws which see them as indulging in criminal activity. Despite this, these groups rose to the challenge, collectivised and empowered themselves to use the condom, and it is all thanks to them that the spread of the virus has somewhat abated. Hundreds of community-led interventions grew across the country, with peer educators making safer behaviours acceptable, one person at a time. Nonetheless, they continue to pay a heavy price for the absence of an inclusive mainstream discourse on sex and sexuality – they live in daily fear of ridicule, violence, neglect and marginalisation.

Condoms left the bedrooms of those who considered themselves beyond risk. And that was the death knell of the discussion on sexuality that the HIV response was mandated to have had among men and boys, women and girls.

In 2009, a parliamentary committee led by BJP veteran Venkaiah Naidu decided that sex education was “against the ethos of our society and would uproot the cultural values we’ve cherished since the Vedic Age.” Instead, the committee recommended “instinct control” and “dignity of restraint”, using course material on the lives and teachings of saints, spiritual leaders, freedom fighters and national heroes to “reinculcate in children our national ideals and values which would also neutralize the impact of cultural invasion from various sources”[1].

As a result, some young people who are in the school system get a few hours of sexuality education every year, quality and content notwithstanding. Young people outside the formal school system just fell off the radar.

In 2001, a writ petition was filed in the Delhi High Court challenging the constitutionality of Section 377 which criminalises same-sex sexual behaviour. After many twists and turns, huge community mobilisation across the country, media pressure and persuasion, the Delhi High Court read down Section 377 in 2009. This was a historic judgement. However, in 2013, the Supreme Court of India set this judgement aside, observing that the High Court was anxious “to protect the so-called rights of LGBT persons”[2].

It was no surprise, therefore, that a UNDP study published as recently as 2014 found that 61% of the respondents associated HIV with shame, two-thirds blamed sex workers, drug users, sexual minorities and ‘promiscuous’ men for spreading HIV, and most alarming of all, considered HIV to be a punishment from God for their wrong behaviours.

This evidence proves beyond doubt that the HIV programme did not get the fundamentals right. After 25 years of a high profile and high investment HIV programme, we seem not to have moved much from that September day in 1998 when the court blamed it all on “undisciplined sexual impulse”.

As long as HIV infection is not decoupled from prevalent notions of sexual deviance and immoral behaviour, the job will remain half done. And this complex decoupling can still be done through conversations on sex and sexuality.

Young people in India are more than ready for this conversation, but can policy-makers rise to the occasion?

[1] See page 19 of the Summary of Work Done by the Rajya Sabha Committees – 2009.

[2] See paragraph 52 of the Supreme Court judgement (2013) on Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code.