If I had a dollar every time I heard an opponent of abortion rights say something like “If you remove the option for abortions, women will stop getting them,” it’s safe to say I would go up a tax bracket or two. In many places today, Global South or North, I would need all of those dollars in order to travel a considerable distance for an abortion that may neither be legal nor safe.

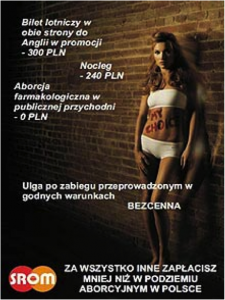

Feminist organisations in parts of Europe where new restrictions on reproductive health care have been implemented (Hungary, Poland, etc.) are protesting these shifts with innovative campaigns highlighting the phenomenon of “abortion journeys”, often called “abortion tourism” or “abortion vacations”. These terms refer to “the long, distressing, often expensive journeys that women are forced to undertake in order to access safe abortion due to restrictive legislation in their home countries” (or states).[1] Ads for fake travel agencies called “Abortourism” or for “Abort Airlines” poke holes in the effectiveness of restrictive laws by bringing the common knowledge out into the open that people who need to terminate a pregnancy will just go elsewhere to do so. The cost is high, but a plane ticket beats the bill (and risk) for a back alley procedure and possible criminal charges at home.

Poster from a protest in Seville, where women carrying suitcases with the slogan Abort Airlines, “Vamos a Londres a abortar.” (“Going to London for an abortion.”) queued up at the airport. It is worth noting that Spanish organizations such as Agora Feminists and CELEM used the looming return of the need for abortion journeys very effectively in their campaigns against proposed legislation that would have severely restricted abortion access; the legislation ultimately did not pass.

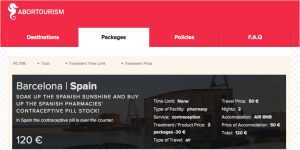

A fake abortion travel agency pop-up that CELEM created as part of activism against the proposed changes. Read about it here.

In many countries with strict laws regarding abortion, contraception is also difficult to obtain, highlighted in this travel ‘package’ from the Hungary-based Abortourism campaign.

The Abortourism-type ads make me want to cheer; especially once I learned some were issued as a counter measure to a “pro-life” campaign featuring Hitler and a bunch of torn foetuses (yes, really). At the same time it’s disappointing that they cater to a narrow audience: those with sufficient financial resources and social mobility to travel internationally. Socioeconomic status/class remains one of the strongest predictors of whether a person will be able to obtain an abortion, regardless of its legality where they live. As Marcy Bloom and Susan Cohen comment, though abortion journeys receive more publicity these days (due to the shock factor, perhaps, that provisions for an important aspect of health care are still denied even in wealthy countries), women who were able have always travelled for terminations. From Kenya to Poland, Mexico to Ireland, abortion remains a class issue.

Thinking intersectionally, even poorer women living in urban areas and/or in the Global North have crosscutting geographic and infrastructure advantages that help alleviate socioeconomic burdens. Proximity to a medical provider who will give a safe and/or legal abortion; access to documentation like passports and insurance cards; dependable public transportation and better overall resource availability, if not from one’s own finances then possibly from organisations dedicated to funding abortion-related travel, all make a huge difference. After abortion was legalised in Mexico City in 2007, numerous states around the capital actually strengthened their laws against abortion in a ripple effect conservative backlash, creating an even larger gap in access for those outside of the urban centre. In a 2014 interview with TARSHI, feminist activist Alejandra Sardá-Chandiramani shared how in response to this nationwide gap, organisations in Mexico City started quietly funding the abortion journeys of women to come to the capital. Previously, Mexican women had travelled to U.S. states like California, a practice that continues for a privileged minority with visas.[2]

The trivializing terms “abortion tourism” and “abortion vacations” have, unfortunately, stuck. When we frame abortion journeys this way, “sex tourism” and “medical tourism” also come to mind, kinds of travel that are often exploitative and at best dismissed as ‘elective’. Saying “abortion” in the same breath as “vacation” is convenient for opponents of reproductive rights who assert the callousness or thoughtlessness of people who terminate pregnancies. “Abortion tourism” implies that women flippantly make the decision to abort, or even look forward to doing so: perhaps when we pack for a seaside excursion, our suitcases are full of the panty liners that fit inside itsy bitsy bikini bottoms, to catch the fallout of the medical abortion we’ll enjoy alongside a daiquiri served by a bronzed hunk named Pablo. While getting an abortion shouldn’t be distressing or shame-inducing, neither do most approach the decision without deep consideration that whatever the reason, this is the best thing to do at the time.

We need to highlight the realities of what ‘undue burden’ means in practice without trivializing the issue as tourism. When a person has to leave their work and family to travel hundreds or thousands of miles to receive medical care, it is hardly a pleasure cruise.

[1] Refer to Marcy Bloom.

[2] Daniel Grossman et al, “Mexican Women Seeking Safe Abortion Services in San Diego, California,” Health Care for Women International 33: 1060-1069, 2012.

Cover image courtesy Youtube