In today’s world, when people ask, “Is she in a relationship?” they are not asking whether the woman in question has friends or relatives or an animal companion or talks to her roses, but whether she has a lover. They ask the same question about men as well. It cuts across genders. In some countries, even passports mention ‘civil status’ or ‘name of spouse’. They have been doing it for a long time. It seems to be an important marker of personal identity. The centrality that relationships have come to occupy in our lives cannot be denied. And, in places where people don’t talk about ‘relationships’, they certainly do talk about and arrange marriages. There seems to be no getting away from it.

It is not the purpose of this article to delve into how this came to pass, but rather, what it means for us. Whether it be marriage or coupledom or just good old bonking, these are arrangements made around sex. Of course, sexual relationships are important, and, inside or outside of relationships, sex is important. But is the importance misplaced? Does it lead us to undervalue other aspects of and in our lives?

For obvious reasons, in the early days of budding love or throbbing passion, one becomes oblivious to many things, including family, friends, and food, all sacrificed at the altar of new sex and/or love. The problem is that even though the fervour may abate over time, the newly coupled unit becomes an entity unto itself. It becomes, and in some cases, is made, central in the sphere that encompasses all kinds of relationships. I am not deriding the fact that people in love or in a relationship want to spend private time with each other, go off on holidays together, hold hands and go for a walk, enjoy a romantic weekend, and so on. I have done it myself.

What I wonder about is how other people (meaning society) give it so much importance. People expect you to show up everywhere as a unit, as if along with acquiring a partner, you have acquired all their friends, tastes, interests, and, even their dislikes. If you legalise your relationship by getting married, the tax people give you a break, the immigration people allow you to live in your spouse’s country even if it is not your own, the medicos allow you a visit if not a say if your spouse is hospitalised, the agent is happy to add your spouse’s name to your insurance papers, and your bank manager smiles at you sweetly when you add your spouse as nominee or joint account holder. Many privileges.

Up to recently these were the privileges only of heterosexual couples. Now, in some parts of the world they are claimed by same-sex couples as well. Some say that’s only fair because we should all – gay or straight – have equal rights and gay people should not be treated as second class citizens. Others say it is not a good idea as it replicates patriarchal norms (marriage being a patriarchal institution), and instead of claiming privilege we should dismantle the whole system of privilege for a few and oppression for others.

Funny true story. When a same-sex couple, whom I know, decided to get married they were questioned by some of their radical feminist friends about perpetuating the institution of marriage. Their response that they were in love and wanted to spend their lives together cut no ice. What did was when, fed up with arguing, one of them said, “We hate our families of origin. If we marry, when one of us dies, nothing will go to them.” How perverse that the logic of hate combined with inheritance law made for a more acceptable justification of marriage than the call of love. It did not defeat the patriarchy but it ended the argument.

Anyway, to come back to the idea of the centrality afforded to ‘relationships’, why are certain privileges only afforded to couples? Why can we not share them with others outside of a romantic or sexual paradigm? Why is intimacy seen as being the purview of lovers? In actual fact, we may often share a greater intimacy with our friends than we do with our lovers. Intimacy that includes the sharing of serendipitous epiphanies as well as embraces the telling of quotidian events, stray recollections, and random thoughts that we do with our friends. Maybe we miss out on something when we value one sort of intimacy over another. A shared belly laugh can be as validating of my personhood as a passionate tumble in bed. The latter I do with my lover, not my friends; the former I can do with both. Shared intimacies. Joy expanded.

Restricting the possibilities of finding intimacy (or love, personal fulfilment, call it what you will) only in sexual/romantic relationships brings with it two problems.

One, it puts pressure on people to ‘be in a relationship’ or run the risk of being seen as being ‘incomplete’ or a ‘poor thing’ (though, on the contrary, my friends who are single, are the very opposite of incomplete, poor things!). There are many people who voluntarily choose, for very good reasons, to be single, and there are many who are asexual – ie they are simply not interested in a sexual relationship. Why is their choice not seen as being as valid as that of someone who chooses coupledom?

Two, it puts inordinate demands on the relationship to fulfil every need: be my lover, my best friend, my sage, my nurse, my muse, my counsellor, my all, be my sweet Baboochamuffin! Hmmm…when did your sexy, wild, irresistible partner get converted into your cuddly wuddly Baboochamuffin? And, can you imagine having wild sex and screaming, “Baboochamuffin!”? Probably not. But, be that as it may.

When people do things together, it is inevitable that they have expectations of each other. This happens in all kinds of relationships: with family, at work, amongst friends, etc. People make adjustments, they consider the other person’s needs, and they may go out of their way to do things in the best interests of the other. However, in the kingdom of coupledom, sometimes this can go too far with the ‘we’ becoming overridingly more important than the ‘I’. If the ‘I’ is subsumed by the ‘we’, what does each one give and each one receive?

“We do this” or “We don’t do that” can easily become a veiled accusation of the other or an excuse for not taking responsibility for one’s self. Maybe we find it easier to locate responsibility on the other person or on the relationship by giving it more importance that it rightly deserves, as long as we don’t have to take responsibility for it ourselves. But, however hard it might be, we need to acknowledge what the ‘I’ brings to the ‘we’, so as to re-own our own power and who we are. Or else, in making the relationship so central and all-important, we will lose our own self. And, maybe sex as well.

—

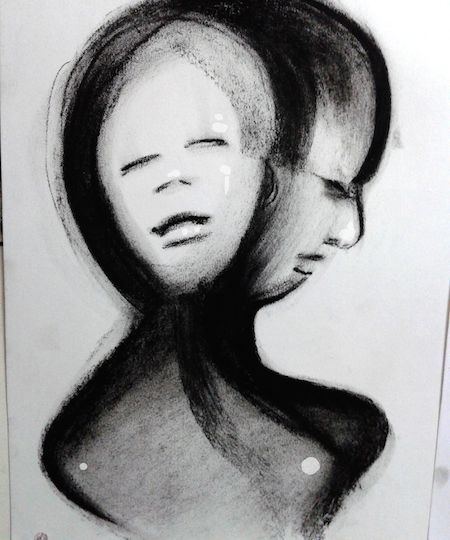

Illustration by Samita Chatterjee