This essay is a brief rumination about queer café’s in urban India. Written as part reflection, part recollection, this essay began as a conversation between two scholars/activists who make their life between New Delhi, Kolkata, and two different university campuses in the United States. Both of us are interested in the materiality of queer spaces in major metropolitan areas of India paying particular attention to the location politics of queer café’s and how such cafés operate as zones of inclusion/exclusion based on class, caste, and gender presentations of diverse queer communities in India. Our reflection is based on recollecting our experiences with two different queer cafés, Amra Odbudh (We Are Queer) in Kolkata and Chez-Jerome Q Café in New Delhi. As queer/feminist/cultural geographers, our recollections will highlight the materiality and location, along with the affective politics of these two cafés. While situating each of the cafés within their respective urban milieus, we also examine how queer cafés navigate the urban real estate market and shifting consumption cultures and how the specific cultural politics of each of the two metropolitan cities of Kolkata and New Delhi shape the operations of the queer cafés.

By Debanuj

Amra Odbudh: A queer sense of place

It is my second day in Kolkata. I am still jetlagged from the 21-hour journey across continents. I am far from the New England university town where I teach, but very close to a place that I still call my home. I walk down the narrow South Kolkata street and meet with three members of the Amra Odbudh collective in a neighbourhood café down the street from my home. We order lychee sherbet, and Bnah-Mih (this café offers a range of East-Asian and Gujarati snacks with rare Bengali delicacies). “Debanuj Da, when do we start the research project?” asks Raina the lead organizer of the Somobhabona collective (trans-women-led labour collective that meets regularly at the Amra Odbudh café). “Chalona, let’s go to our café,” says Nandini. I cannot wait to visit this new queer café in Kolkata. I have read newspaper coverage of the place on Facebook posts and Instagram images. The promise of a Bangla style adda over “ek cup chaa” (one cup of tea – an endearing way of suggesting “let’s hang out and catch up over tea”) a la queer style has lured me back to Kolkata despite the scorching heat. We hail an Uber and merrily ride away towards Jadavpur, an area of Southern Kolkata that has seen a huge growth in the past decade in malls, high-rises and flyovers connecting two major highways. As a result of this, Jadavpur now has a higher population density. This is evident in the unplanned growth of buildings, traffic jams, and a mix of pedestrians, rickshaws, motor cycles, and a greater number of cars along the narrow lanes of the Jadavpur area.

Amra Odbudh Café was started by Nandini Moitra and Upasana Agarwal with the help of close friends. During the time of my visit the café was collectively led, with labour for the everyday management being shared within the collective. The collective of friends took on the task of painting the walls, patching up holes and repairing some of the doors and windows. The cost of these repairs was met by their meagre savings. As our Uber entered the Jadavpur four corner crossing, we were greeted by traffic, pedestrians, and cycle rickshaws along the narrow street. We had to get off and walk through the narrow lanes occupied by rickshaws, bikes and a steady stream of pedestrians. I was following Nandini, Upasana, and Raina. On both sides of the street were tailoring shops and convenience stores selling sweets, chocolates, beverages. The lights were low, there wasn’t much of a glitzy feel to the stores. In other words, the café was located in an everyday Bengali middle-class neighbourhood. The building was quite shabby from the outside, and fit in perfectly with some of the other older buildings that dotted a dead end on which the café was located – a mundane, everyday location providing the café a warm neighbourhood adda feel. Adda is a form of dialogic exchange between friends, and is considered one of the major modes of knowledge production in Bengal. The café provided the perfect dreamy atmosphere for adda Queer Bengali style.

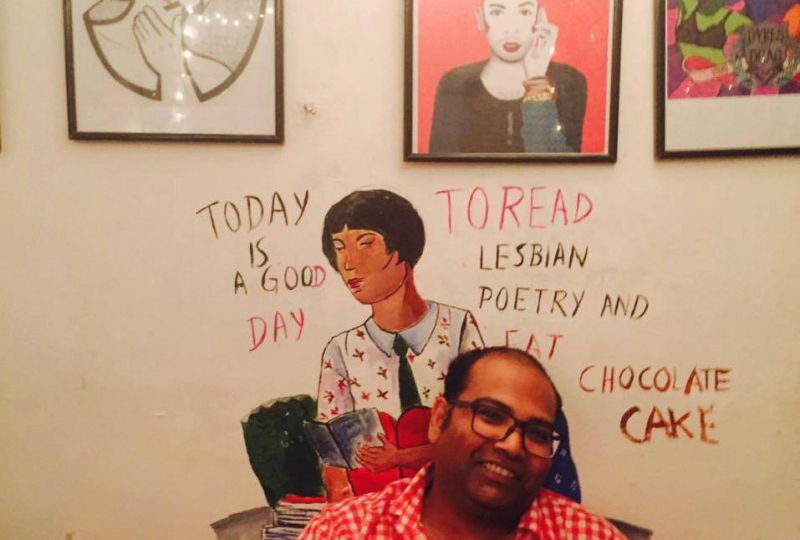

I walk inside the building and climb the stairs. I am greeted by two kittens (the café pets). The walls of the café are painted bright red and white. Dim lights provide a very utopic feeling to this place. I touch the cool walls as a way of feeling the murmurs of many queers who painted quotes from poets and faces of transgender/Koti/ Lesbian and gay activists. One such quotation reads, “It is a good day to eat cake and read Lesbian poetry.” We sit on the floor cushions and start our adda. I feel at home. I am introduced to Sunita and Sunny[1], a runaway lesbian and transmale couple, who are staying temporarily at the café. A veteran trans/Koti activist has been provided with a temporary room, since she is healing from a stroke. The café collective has been crowdsourcing money for her medical treatment. The café is not a regular commercial venture yet, rather an event-based queer collective space. Several members of Somobhabona are hanging out at the café this evening. It is a safe space to gather and put on make-up, before venturing out for cruising or khajra (a term that connotes informal sex work in the Koti community). We laugh, exchange gossip about the queer activist scene in Kolkata, and, Upasana tells me about their plans for the café.

In the summer of 2017, I returned to the café several times in order to organize focus groups and storytelling workshops for my research project. On a rainy July evening, as I entered the café, I realized that a major conflict was being processed within the collective. It seems that Sunita (the runaway lesbian) had beaten up Sunny (her partner). Raina and some of the members of Somobhabona had intervened, and asked the couple to leave the café overnight. This situation had now become a flashpoint for the café collective to process basic rules and ethics for the café. The collective did not prevent me and some of the other queer folks who had shown up to hang out in the café from joining the discussion. The conversation turned to processing intimate partner violence, the differences in gender and class identity with the café collectives, and how Nandini felt a sense of urgency around this issue, since the property belongs to her family.

The openness of the café collective in welcoming me (while I need to acknowledge that being a researcher from the US, as well as a long time queer activist in India & the US gives me immense privilege and access to multiple spaces in Kolkata) as well as other folks who happened to be there, gestured to me the very open and chaotic process of operating the café. Such a chaotic process need not be understood as a failure of the collective to professionalize café management, rather the open and chaotic nature of management allows for multivalent political potentials. The café is a site for celebrating book releases, showcasing films and artistic works, as well as regular hangouts. The collective makes a small earning through selling tea, coffee, and creative food items such as gondhoraj chicken (fried chicken with an aromatic lemon that is specific to the West Bengal area). Throughout my stay this summer, my hangouts in this utopic queer space confirmed for me how the café signifies queer politics as an incomplete project. Queerness is a kind of becoming, without a prefixed destination. The openness of the café, the porousness of the collective, birthday celebrations, and dance rehearsals by one of Kolkata’s first trans/Koti modern dance troupe make this otherwise mundane building rife with queer potential. A place that I wish return to, and cherish its memory even when I am far away from Kolkata.

Chez-Jerome Q Café

On November 12, 2017 Delhi celebrated the tenth anniversary of the queer pride parade in the city. While the past decade has witnessed a descending number of masks and ascending density of queer bodies, the parade has remained a chorus of dhol beats and political sloganeering down Tolstoy Marg. However, queer publics in Delhi have certainly swelled beyond Lutyens Delhi, South Delhi NGOs, and the inner circle salons hosted in the homes of liberal queers, if not further. These developments are marked by the growing surge of “LGBTQ-friendly” clubs, gay saunas, university-based queer collectives, and the #queerdilli which assiduously archives the spatiality of this renewed queer habitus.

By Sambhav

Disrupting and readjusting spatial boundaries regulating gender and sexuality in the city, these geographical claims have also paved a way for a queer cosmopolitanism which often entails a different set of exclusions. The co-founder of the Chez Jerome-Q Café, Sambhav Dehlavi says, “If one were to ask to whom does the queer nightlife belong, the answer would be gay men.” In order to challenge this and enable a safe space free of misogyny and transphobia for women, queer and gender non-conforming people, Sambhav crafted the rooftop queer café perched in the nook of Mincha Wali Gali in Lado Sarai that skirts the peripheries of South Delhi. Over the past few months, the café has organized and curated gay-speed dating events, lesbian ladies nights and queer karaoke sessions among other things. Sambhav, who is not associated with the café anymore, recalls the euphoria it garnered as it opened its doors earlier this year in April. The media fervently reported the café to be the coming-of-age of not just urban queer subjectivity, but an awakening of the “sexually repressed” India itself.

Overlooking the Qutub Minar with the rainbow flag fluttering through the early winter winds of Delhi, the Chez Jerome-Q Café today is sparsely populated. This is not necessarily symptomatic of a hazed queer geography, but to the contrary, is indicative of its growing expanse in Delhi. The temporality of the café exemplifies the shifting spatial economies of the city which determines how subjectivities interact with space. The LBT party organized by the Delhi Queer Pride 2017 in early October struggled to locate a venue for a dance party, as clubs one after the other refused to host a queer gathering. A five-star hotel, The LaLit which has remained the only place to accommodate openly queer get-togethers, hosted the party in one of their quainter basement bars. Within a month Gaysi, an online queer community, organized their 2×2 bar nights at Hauz Khas Antisocial. Similarly, Queernama was set to host a post-Pride meet and greet at Ivy & Bean, Shahpur Jat. So, over the course of just three months, there was an oscillation from the absence of public spaces of sociality to multiple establishments coming forward to accommodate queer events. Shivani Agarwal, a queer-rights activist, upon her return to the city after six years notes, “There is a huge increase in support groups and organization, especially in Delhi.” Sambhav seconds this while also drawing our attention to the challenges carving out queer spaces in the city entails. He says, “Although my past association with Chez Jerome-Q Café was a success, there is no doubt about the fact that the café depended on a capitalist logic to survive. We tried our best to channelize this to retain an egalitarian and inclusive space for the community.” The café offered discounts for trans customers and hosted several activist events to ensure accessibility of the space to a larger section of queer people. However, now as the café’s ability to safeguarding a queer space is dwindling, it remains important to ask what challenges these new geographies raise for radical queer politics in Delhi.

The nascent yet fast-emerging queer cosmopolitanism and its renewed sexual spatialities in Delhi have also come to mirror social and material hierarchies in many ways. These new spaces of queer desire, camaraderie and collectivity continue to privilege people who derive cultural capital from their caste and class positioning. Gated establishments that deny trans people entry and harass working class queer folks for valid IDs, largely remain inaccessible to many, reiterating multiple forms of alienation. Even as these spaces offer a promise of care and safety to some of us, many queer people continue to precariously tread through state-manufactured surveillance projects governing this emergent urbanity.

Toward Queer complicit futures?

In this critical reflection about the two café’s, we argue that such spaces need to be understood within the changing urban landscape of their respective cities. Amra Odbudh exists within the chaotic growth that dots South Kolkata’s landscape. The building is hidden from the main street, located within a cacophony of human noise, barking stray dogs and burgeoning traffic. The café is possible since Nandini’s family owns the building. However, cadres from the ruling party have visited the café asking for hafta (weekly payment for maintaining a business). The café collective has argued that there is no commercial venture in the space. The chaotic collection of trans/Koti working class activists, middle class university faculty and students, performing artists and lovers seeking privacy from the bustling city gesture a very queer sense of place. The café collective has organized fundraisers (a recent fundraiser of supporters was held at Cardiff University in the UK), and remain complicit with screening activities such as hooking up or meeting clients for sex work at the space. While many trans/Koti folks have levelled charges of exclusion, many still gather there and happily mingle with intellectuals and performers.

The political valence of Amra Odbudh is very different from a commercial venture that Chez Jerome Q Café has now come to be. The latter desires to be a slick operation in the midst of a touristic area of New Delhi. The owner today is navigating the complex conundrum of real estate and profitability within the wider sexual economy of Delhi. The enhanced prices, its locative operation and the embedded cultural codes woven around the café have translated into exclusion for working class and Koti community members. Thus, substantive participation in this queertopia is dependent upon one’s ability to perform urban cosmopolitanism. Although Sambhav has now parted ways with the café, he hopes to one day retrieve his vision of a radical queer café which would enable a trans-inclusive space for queer joy, community and desire. The question remains whether Delhi’s urban futurity would enable a substantive queer space amidst cultural clusters of consumption, and timeworn social hierarchies morphed into contemporary cosmopolitanism.

In conclusion, we suggest that queer space need not be thought of through the binary of complicit or oppositional space. Perhaps, complicity with real estate politics, demands from political parties and commercial ventures coexist with queer radicalism. Each of these spaces is different, and both offer a space with queer sensibilities. Queer cafés are not exempt from the fast changing landscape of Indian metropolitan areas and offer both inclusion as well as exclusion from the promise of a queer utopia.

[1] Names have been changed in order to protect confidentiality. Upasana, Nandiani, and Raina are public about their relationship with the café and provided consent for my research.