This essay is part of the #IndianWomenInHistory campaign for Women’s History Month to remember the untold legacies of women who shaped India, especially India’s various feminist movements. Each day one Indian woman is profiled for the whole of March 2017.

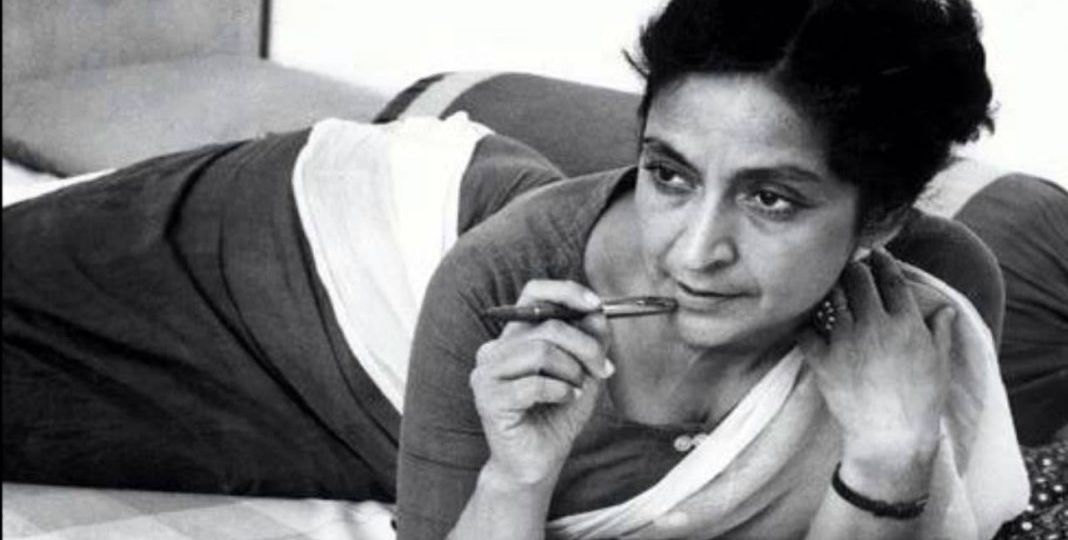

Amrita Pritam was an iconic Indian writer, whose works as well as life, were a bold statement that redefined not just the Punjabi literary canon but also found new words and images for how Indian women perceived themselves.

The famous writer and journalist Khushwant Singh had once told Amrita Pritam that the whole story of her life was so inconsequential and brief that it could be easily contained within the small space at the back of a revenue stamp. She remembered the joke and called her autobiography Raseedi Ticket (The Revenue Stamp). This one incident probably sums up this prolific and ground-breaking writer’s philosophy of life – “My work/my life will be my answer“.

Life and Times: The Beginning

She was the only child of Kartar Singh and Raj Kaur, a Sikh couple who named her Amrita Kaur in 1919, in Gujranwala, Punjab in erstwhile undivided British India, now Pakistan. Her father was a school teacher by profession but is also believed to have been a small-time poet. The environment in her early home was deeply spiritual; her father was a pracharak/Sikh religious preacher as well. Along with religious learning, she also inherited her love for literature from him.

Amrita was born a rebel, a questioner of norms, a devil’s advocate of sorts. She asked difficult questions and challenged those things that everyone accepted as the norm. This gets reflected in her literature and personal life much later and throughout.

In her autobiography, she recalls that once as a young girl she noticed water being hawked at the railway platform as Hindu water and Muslim water. She questioned her mother — “Is water also Hindu-Mussalman?” Her mother’s reply – “It is this way here…” – was definitely not satisfactory for the young rebel. Later, a very young Amrita raised her voice against her conventional grandmother, who kept separate utensils for her Muslim visitors. It was “….my first baghavat (rebellion) against religion“, she writes therein.

Amrita, the young critical thinker who was already questioning a lot of morality and religion, turned almost atheist after the death of her mother when she was barely eleven years old. She realised the uselessness of prayer as all her prayers to restore her mother’s health had turned futile and stopped praying altogether after her mother passed away.

The family then moved to Lahore where the young teenager found herself overburdened with responsibilities of running a household. In such depressing and challenging circumstances, Amrita found succour in writing. Her exceptional talent did not go unnoticed and as a result her first anthology of poems ‘Amrit Lehran’ (Immortal Waves) was published in 1936 when she was barely 16 years old.

Trying to find some grip on life the young Amrita married Pritam Singh and became Amrita Pritam around the same time, a name she carried all her life. Pritam was the son of a hosiery merchant and an Editor, the couple had two children, but according to Amrita the union was loveless and devoid of any passion or deep emotion.

Writing Career

Once Amrita started writing in 1936, she continued doing so prolifically; in spite of the dissatisfactory marriage by 1943 she had already gained much acclaim and had six anthologies of poetry to her credit.

Her initial work consisted mainly of romantic poems though she gradually gravitated towards the Progressive Writers’ Movement – a literary movement where writers were writing about socio-economic concerns of their society and times. In 1944, in a poetry collection titled ‘Lok Peed’ (Anguish Of The Public) Amrita’s first social poetry emerged and she criticised the economy being depleted by the Second World War and the disastrous Bengal famine of 1943.

Her increased involvement in social work in the mid-1940s, her working with the Lahore Radio Station for a brief period and her angst at the helplessness of the commoners especially women made her works around that time become more and more rebellious and socio-political in nature.

The year 1947, the partition of the country, became a watershed for her both as an individual and as a writer. She witnessed innumerable, unspeakable human tragedies. The communal riots that continued for several months during the refugee influx to and fro from both sides led to such mindless violence that like most other survivors of this historic tragedy, it left an indelible mark on Amrita’s mind for the rest of her life.

Amrita, a young woman of 28 moved to New Delhi from Lahore. By now she was sure that her marriage was just imprisoning her body and soul. It was in this state of emotional turbulence that she penned one of her oft-quoted and most famous poems ‘Ajj Akhaan Waris Shah Nu’ (‘Today I invoke Waris Shah’) in 1948, invoking the famous Sufi poet Waris Shah.

In this poem she challenges the tropes used in romantic poetry – not just Punjabi or Sufi poetry, but the entire literary canon – where the woman is just seen as a consort/beloved and nothing more, her suffering and her dilemmas completely overlooked. Also, her vision of love here became significantly broadened and delved into the other worldly Sufi realms.

Nirupama Dutt, a prominent Punjabi/English writer herself, who was a friend and confidante of Amrita in her last years and has translated some of her work, writes in an article that in Amrita’s literature love wasn’t viewed as ‘a narrow man-woman exchange’. She was deeply hurt and saddened by the loss of a composite Punjabi culture and felt a deep sense of betrayal like many other survivors because of the mindless bloodshed during and in the aftermath of the Partition. Nirupama says that probably she had turned to Waris Shah to express this deep-seated anguish because he had composed one of the most famous and immortal love legends of Punjab.

“Aj akhaan Waris Shah nu

Kiton qabran wichon bol,

Te ajj kitab-e-ishq da koi

Agla varka phol”

(I call out to Waris Shah today

To speak out from his grave

And turn today the next leaf

Of the book of love.)

(Original Amrita Pritam, Translation: Nirupama Dutt)

Soon after in 1950 her novella ‘Pinjar’ (Skeleton/Cage) came out. This was made into a Bollywood film years later in 2002 and remains till date one of the few Punjabi works on the partition of India from a woman’s perspective.

Amrita began working in the Punjabi service of All India Radio, Delhi and continued serving there till 1961. In the 1960s, post-Pinjar, the feminist streak in her writings became more predominant and vociferous.

In Pinjar, Amrita depicted the immense human tragedy through the lives of young Muslim, Sikh and Hindu women who were abducted, raped and killed. Several of these women were permanently separated from their families and those that were reconciled were not accepted and labelled ‘tainted’. Many of her poignant poems during this period also encapsulate the silent suffering of women in such a conservative milieu where behind their suffocating veils these women remained perpetually doomed and belonged nowhere.

Several of her later works – ‘Kaal Chetna’ (‘Consciousness of Time’), ‘Kala Gulab’ (‘Black Rose’), and ‘Aksharon Kay Saye’ (‘Shadows of Words’) all had a strong rebellious undertone.

In 1964, she founded a Punjabi literary journal called Naagmaṇi, in which she started showcasing the work of emerging and reputed Punjabi poets and writers as well as translations of foreign writers, as her contribution to a growing new canon of new literatures in India.

Amrita’s literary legacy is vast not just in its impact but its volume too, consisting of more than a hundred books of poetry, fiction, biographies, essays, and even a collection of Punjabi folk songs – many of which were translated into several Indian and foreign languages as her fame and reputation grew.

Official Recognition

In 1956 Amrita’s work ‘Sunehey’ (‘Messages’) was conferred the reputed Sahitya Akademi Award. Later she was also awarded one of India’s highest literary awards – the Bhartiya Jnanpith Award for ‘Kagaj Te Canvas’ (‘Paper and Canvas’). She was also the recipient of the Padma Vibhushan, India’s second-highest civilian award and was elected a member of the upper house of the Indian Parliament, the Rajya Sabha.

The Legacy Of Her Life And Her Work

Amrita became the first Punjabi woman writer to move out of the shadows of the contemporary male writers and created her own niche in Punjabi literature. Not just a poet, she was indeed revolution personified.

This fiery woman survived and walked out of a loveless marriage, she bore with courage the agony of being uprooted from her homeland during partition and went on to lead an exemplary life.

Her life choices, as well as her literature, were definitely ahead of her times. She gathered the courage to walk out of her loveless arranged marriage, which was unheard of in those times, and openly acknowledged her love for the famous poet Sahir Ludhianavi. She lived the rest of her life with her companion Imroz, her relationship with whom resulted in some of her most beautiful poems and has served as an example to look up to for women who dare to be themselves in a world that is constantly trying to put them into watertight compartments – daughter, wife, mother or the more intangible ones – chastity, morality, virtue.

This choice of being together outside wedlock in 1958, when living together was not even heard of, became one of the most defining statements about her non-conformity to the norms of ‘ideal Indian womanhood’. This courage allowed her to transcend all social sanctions and the formal legitimacy of marriage.

Amrita is mostly known for her passionate and unabashed love poems, hitherto unknown in the whole canon of Indian literature by women. She talks about the woman’s body as an independent entity as well as a contested space by a man’s love and the tradition’s pressure to procreate.

These revolutionary ideas and expressions made some contemporary critics describe her as a feminist much before feminism. She was a firebrand poet who would not mince any words just because of expectations from her gender.

Amrita Pritam’s legacy for women and subsequent generations is to intentionally challenge status quo, trying to use art to challenge accepted taboos and redefine them. Be fearless, unabashed and courageous in the face of crude censorship and charges of obscenity, of raising and using your voice to speak as you see the world – not in the manner that the world expects you to speak.

The last of Amrita’s love poems titled Main Tenu Pher Milangi (‘I shall meet you again’), is now not just a piece of poetry but a legend in its own right, having been recited by many including the famous writer Gulzar. This poem is dedicated to her long-time companion Imroz and is now seen as her perfect epilogue. It showcases her unique perspective on life, her vision of love and the world and her undying hope for a world full of love and peace.

I will meet you yet again

How and where

I do not know

Perhaps I will become a

figment of your imagination

or maybe splaying myself

as a mysterious line

on your canvas

I will keep gazing at you.

Perhaps I will become a ray

of sunshine and

dissolve in your colours

or embraced by your colours

I will paint myself on your canvas

I do not how and where –

But I will meet you for sure.

Maybe I will transform into a spring

and rub foaming

droplets of water on your body

and like a coolness I will

ease into your chest

I know nothing

but that whatever time might do

this birth shall run along with me.

When the body perishes

It all perishes

but the strings of memory

are woven of cosmic atoms

I will pick these particles

Re-weave the strings

and I will meet you yet again.

— Translated from original Punjabi “Main Tenu Phir Milangi” by Pooja Sharma Rao.

Also read: एक थी अमृता प्रीतम: पंजाबी की पहली लेखिका

References

- Scroll – The Story of Amrita Pritam’s Final Love Poem

- Amardeep Singh – Reflections (And Questions On Amrita Pritam)

- Independent – Amrita Pritam: An Obituary

- The Hindu – An Alternative Voice of History