TARSHI

Greetings from TARSHI! We are very pleased to bring to you the first issue of In Plainspeak, our new monthly…

Not only has evolving discourse on sexuality influenced the fate of how sex work is understood, but also with the growth of sex workers’ rights movements, discourses on sex work are now being able to influence how we think about sexuality. In our issues on Sex Work and Sexuality this month, we hope to be able to traverse some of these convergences.

What is the self, and what does it mean to give care? Philosophers, activists, artists, scientists, people of all inclinations and positions have pondered on, played with, and struggled to come to meaningful definitions about the issues these questions address. Without care, can there be a self at all?

With Assisted Reproductive Technologies, science has managed to use technology to prise apart previous associations between reproduction and sex. With gender, class and queer theory, the social sciences have prised apart previous associations between gender and sex. We have found that knowledge through science, like knowledge of sexuality, can’t be pinned down to absolutes. “The more you know, the more you know you don’t know,” said Aristotle. While science may value the systematic and objective, it cannot escape the baffling convolutions of lived experience. How does life influence knowledge, and knowledge influence life?

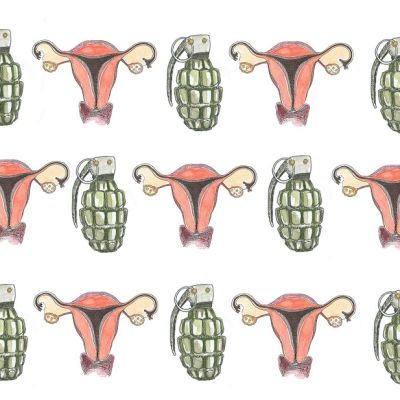

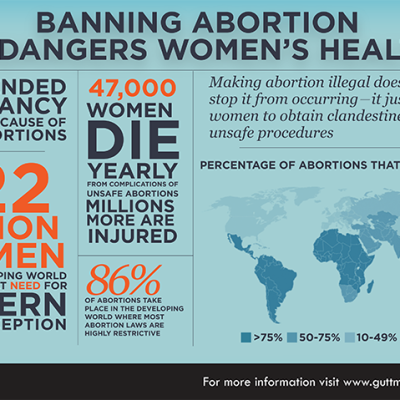

This month we bring a range of contributions on the issue of Safe Abortion from activists working at the grassroots for the sexual and reproductive rights of women to have access to safe abortion.

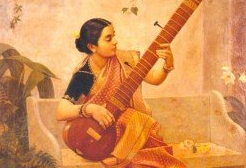

Is there a relationship at all that cannot be defined by love? And, if we were to begin talking of relationships other than romantic love, how would we speak of sexuality? Upon this deliberation, we realised that our Love and Sexuality issue seemed to revolve around romantic love and sex. The departure this issue on Relationships and Sexuality makes is to try and incorporate forms of relationships that might not be about romantic love but have their own kind of romance, and facets of sexuality that might not be about sex per se but will place its interest in alternate relationships to it.

Happy New Year! We hope all your desires and expectations for 2014 are fulfilled. Despite everything that has happened, we…

“The writer cannot be a mere storyteller; he cannot be a mere teacher; he cannot merely X-ray society’s weaknesses, its…

For as long as we can conceive of the existence of human civilisation, we can expect there to have been people’s movements. The term ‘people’s movements’ itself refers to the inexorable nature of the human being: things always change; they fall apart and come together in dynamic fluidity, and this uncontainable, organic spirit of constant flux is some of the joy of living.

How much do our parents teach us about ourselves? If science and psychology have proved that sexuality and sexual development grow and bloom in the course of our lives along with our other faculties, what role do our parents have in what we learn about sexuality? And, as parents, surely there’s so much we learn about sexuality, ourselves, and everything else from essaying the role? To parent is to learn how to teach what we already know, and to be able to receive more than a few surprise lessons ourselves.

“Does my sexiness upset you? Does it come as a surprise that I dance like I have diamonds at the…

Aspects of sexuality such as aesthetic taste, body image, sexual orientation, desires and aspirations, self-esteem, gender expression, reproductive choices, and more, are all interdependent with the impact of money in our lives and that of those around us. Indeed, our systemic relationship with money has a direct influence on how we ‘value’ ourselves.

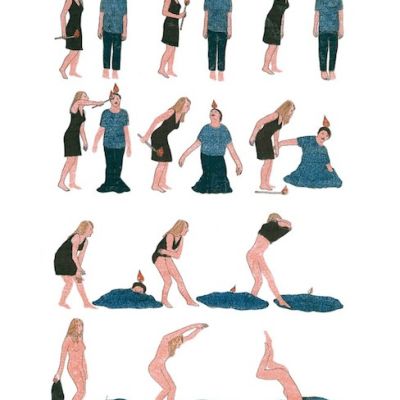

Movement. Stillness. Travel. Free flow. Restrictions. Borders. Us and Them. Movement takes us closer to our destinations and sometimes forced…

Talking about migration would be talking about what happens with the crossing of boundaries. Boundaries of culture and climate, and boundaries of visibility, where a change in semantics can come to render what was invisible visible (an accent, perhaps a way of dressing, one’s values and ideas, the experience of being surveilled as an alien), while also allowing the migrant certain new freedoms to be invisible (anonymity where ‘nobody knows your name’, and certain kinds of agency one may not have enjoyed back home).

“Was I ever crazy? Maybe. Or maybe life is… Crazy isn’t being broken or swallowing a dark secret. It’s you…