One of the most common things I hear on the Delhi roads is “behanchod”[1] followed by a graphic, sexual and often creative usage of further abuses. The person saying it is more often than not a man. Not that women don’t partake of this manner of conversing (for instance, I do). But public spaces in cities like Delhi are dominated by men. The majority of public spaces being occupied by men aside, the politics and dynamics of men using sexually-explicit abuses vis a vis women[2] has had enough ink spent on it. I do not wish to add to it at the moment. However, there exists, I argue through this piece, an intricate relationship between the verbal abuse culture in the Indian state and its relationship with Kashmir.

To begin with, verbal abuse centred around sexually defiling women is part of the culture of violence that is deeply rooted in patriarchy, caste and religion. This culture of violence is founded on the abuse of women of the ‘other’ community. ‘Other’ in popular Hindu perception is the Muslim other. However, violence on the bodies of Adivasi, Bahujan, or Dalit, though structural and institutional in nature, is silenced and/or ignored. Attempts are also made to overlook this violence, through an implicit understanding that these groups are inherently Hindu. While abuse in the name of religion is portrayed as the basis of ‘national consciousness’, that in the name of caste-ethnicity is erased or silenced.

The culture of verbal abuse makes men fight with each other to prove their masculinity is superior. The abuse often acts as a precursor to physical violence, manifesting itself either through violence between men, or on women and non-binary people. The verbal abuse is often accompanied by grandiose bodily aggression, completing the performance of a certain kind of masculinity.

Abuse (verbal) is seen as a way of emasculating a man. Nothing is a bigger cause of worry or concern for Indian heterosexual men as a loss of their masculinity. Virility is celebrated. The aim of this argument is not to simplify masculinity or equate it in India with heterosexual masculinity, but to draw connections between heterosexual masculinity and an all-pervasive culture of abuse. The abuse aimed at the woman of a community is often seen as a way of targeting the men of that community, by marking him ‘incapable’ of ‘protecting’ their women.

Veena Das in her seminal work, Life and Words (2006), situated in the narratives of women in post-partition India, argues that the state, to maintain ‘order’ and to ‘protect its women’ – an attribute of a masculine nation-state – shifts the business of the family to the order of the state i.e. control of the reproductive capacities of women. The social contract of family becomes the sexual contract of the state, i.e. by placing women within the ‘domestic space’ under the ‘control’ of the ‘right’ kind of men. During partition this played out in the ‘reclaiming’ of the ‘abducted women’. The same logic and dynamics played out in the post-partition period during communal riots, when the Muslim became the other from whom ‘these’ Hindu upper-caste women must be protected. During these riots, as history has witnessed, the nation-state sides with the Hindu majority and translates to rape and abduction of the ‘other women’. The nation, in my reading then, is a weak heterosexual masculine figure needing to ‘domesticate’ a much more powerful gender and sexual expression to justify its very existence, hence the conceptualisation of mother India.

Mother India, a creation of the nationalist movement, has been invoked like any Hindu goddess time and again to serve different rulers/ regimes/ ideas/ projects etc. The mother India was most recently invoked to unilaterally ‘integrate’ the state of Jammu and Kashmir by abrogating Section 370 of the Indian Constitution which formed the basis of a relationship between India and the state of Jammu and Kashmir.

In the unfolding of this abrogation, I situate the link between the verbal abuse culture of the Indian state and India’s relationship with Kashmir. On the Indian side, there was loud, boisterous, often disgusting celebration of the nation. The photos making the rounds included one of a group of people holding a map of integrated India showing both Pakistan-administered Kashmir and Aksai Chin wearing a pagadi (Upper-caste North Indian headgear) marking the nation as one man, dubiously making it father India. Also, through this, signalling to the two neighbours the real intention of taking back what India believes is rightfully “hers”. During a rally in the run-up to the Haryana elections, Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar said that post the abrogation of Article 370, men from North India could get fair brides from Kashmir. The verbal abuse culture manifested itself in blatant occupation and control of a territory, as much as claims made on bodies and personhood of women who are under a communication blackout.

Kashmir has been imagined via photography and cinema as a ‘female territory’ (Kabir, 2009). It has been lauded for its natural beauty. It was the popular honeymoon spot in the 1980s. Both my maternal grandparents and my parents went there for their honeymoon. Of the things I heard about Kashmir before I ever went there was just how beautiful a place it is. The land was made desirable. Its women and men beautiful and dainty. With the abrogation, pictures, discussed below, of masculine bodies circulated in Indian media celebrating the ‘integration’ of this land and these bodies. To mark them as ‘ours’, the claims for a ‘fair bride’ implying control over the reproductive capacities of women, to produce ‘Indian’ and by extension Hindu kids.

In the midst of this shameful celebration and jingoism, two images that circulated spoke more about this fragile masculinity than anything else. A Kashmiri man was beaten up by some Indians, assumedly Hindu men, and was made to wear women’s clothes. It was to not only to emasculate the body in question but also send a message that India is a heterosexual-patriarchal nation. Any body not living up to this standard of being a heterosexual man capable of protecting women, was a body to be abused and ridiculed. The act of making this body wear women’s clothes was evidently to mark the body as ‘lesser’, and by extension, to mark any body that doesn’t fit into the neat binary as something to be ridiculed. This is the same India that boasts of being progressive on accounts of judgements and Bills passed in the name of non-normative bodies.

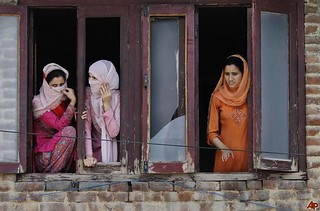

The other image doing the rounds was of women, protesting against the state and its occupation. The spectacle of protesting women in Kashmir reclaims their bodies, which have been routinely abused and violated, and converts them into bodies of resistance. It turns the popularly understood rules of war and conflict on their head and marks their roles as retaliating participants. But it is also about women from this dainty land, these dainty bodies, who the men from India want to marry, standing up against the big occupying bully.

Mother India may need its men with fragile masculinity, and dare I say small penises, but it doesn’t know what to do when angry women stand in front of it challenging it. Reminds me of a moment in the past when Meira Paibis in Manipur stood naked asking the Indian army to rape them. All one saw of the army was it hiding behind the window covering its face.

[1] The word literally translates to sister-fucker, but being colloquial, its usage is parallel to motherfucker in English.

[2] I refer here to both more men on an average using abusive language by the sheer virtue of their numbers in public spaces. I also refer to abusive terms that address women.

Featured Image Source: Kashmir Global/Flickr