This article was originally published here.

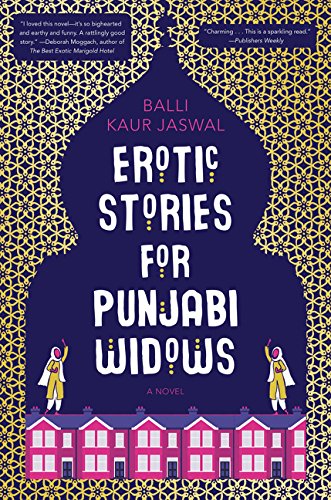

Much like any good erotic encounter, Balli Kaur Jaswals’ 2017 novel, Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows, is a delightful romp that comes to a satisfying, sweet climax and an urge to fall back on the pillows. The novel straddles (pun very much intended) three distinct genres – literary novel, erotica and mystery/thriller – and is peopled with surprising, tender characters that serve an action-packed plot. The stage is set when Nikki, our young protagonist, is hired by an enigmatic, abrasive local gurudwara community director Kulwinder Kaur, to teach an English-language adult literacy class to some Punjabi widows. Nikki is written as a rebellious, feminist, ‘modern’ British-Indian woman who defies the expectations of her more conservative family. She soon finds out that her new students,whom she perceives as drab and wholly sexless, have a naughty side to them – they’re more interested in inventing and sharing sex stories than in learning their ABC’s. Nikki goes along with it, keeping the true nature of the classes a secret from her boss. As the story progresses, other more sinister secrets are revealed, which shine a light on some of the issues facing the British-Indian community in the London suburb of Southall. Though set off Indian shores, this novel is as 21st century South-Asian as microwaved daal in the issues it addresses peripherally (colourism, consent) and intentionally (the policing of women’s bodies and sexualities, honour or izzat, female desire and community loyalty).

The story is so well told and is written with such a light, deft hand that it is almost easy to miss what makes it so quietly radical. To review it within the scope of exploring the coming together of literature and sexuality we must begin with its central cast of characters– the widows. Unlettered, almost invisible, many of them greying and stooping, they neatly upend our ideas of who gets to write and enjoy good literature. The oral tradition of story-telling in South Asia is by no means new, but when one of the widows, Manjeet Kaur, says, “I like that what I imagine gets put down on paper,” she reveals that there is more intentionality in what the widows are doing in their classes. They’re not just getting together for giggles and dirty chit chat – they are authors that you’d better take seriously. The classes from that moment onwards, take on a semi-steady routine. Some widows narrate their stories orally to have them transcribed by the only one of them that can write English. Others write in Gurmukhi. A new set of creative processes is organically born. The widows critique and praise in real time,use prompts (from an old Playboy magazine), address writers’ block,untangle plot knots, and offer suggestions. This is another way in which the characters do not conform to the traditional way of making literature – writing isn’t an individual effort here, but one in which writer and reader come together in a heady, symbiotic relationship built on trust and vulnerability.

Then there are the stories themselves, the sexy literature, which bring together pleasure and fantasy in a way that centres a female expression of desire in new and interesting ways. In the novel, Jaswal skillfully weaves the erotic stories through the fabric of the main plots in a way that makes both elements speak to each other. Each erotic story brings something of its writer to the page. In fact, it is interesting to play a little game where you enjoy the stories but also perceive what they reveal about their writers. It is touching, for instance to see how a lived experience of shame (a mole which has been regarded as unflattering) is rewritten to become a desirable trait in a story. The stories also reveal fantasies that break the conservative model of sexuality imposed on the widows as wives or mothers (a new bride starts out demure and shy and then gets very creative). One story subverts heteronormativity in a thrilling same-sex love scene, another defies ageism and yet a third takes on the rich literary tradition of magical realism when a tailor cursed with celibacy is seduced by a goddess brought to life by his secret desires. The erotic stories are deeply situated in the political, geographical and historical realities of their writers, which make them all the more intriguing and explosive.One might wonder, as Jason, one of the few male characters in the novel does, where these widows, married young and then confined to their Punjabi homes and neighbourhood, get the ‘exposure’ to write so creatively. Nikki addresses this by pointing out the instinctive nature of sexual pleasure, “You and me… we learned about sex after we learned the other basics – reading, writing, learning to use a computer, all of that. To the widows, sex comes before all of that.”

It is a telling moment in the novel, where we are able to perceive how Nikki, who starts out as a teacher, is also learning from her students. The widows use an idiom and language – vegetable names for sexual organs, ghee as lubricant– that is rooted in their experience of desire. As the novel progresses, you get a sense that this literature produced organically and without ostentation is also providing the widows with something more tangible and political than the joy of creating. The stories are conversation starters and the classroom becomes a space of solidarity and sisterhood, so that racy sex tips that would make the most bold among us blush sit alongside fond, dewy-eyed remembrances of husbands long gone and an exchange of memories that speak to a shared experience of loss.

The lives of the other main characters, Nikki, Kulwinder Kaur, and Tarampal, the only widow who didn’t participate in the story writing, are also impacted by the stories, but this is just the tip of the iceberg. Anyone who loves reading knows that good, meaningful literature insists on being read. So (spoiler alert) despite every precaution, the erotic stories are leaked and fly out of the classroom into Southall and beyond, creating ripples of satisfaction, confusion, and, if Southall gossip is to be believed, women that are finally taking charge in the bedroom. The stories spread, through clandestine, furtive networks from gurudwara to gurudwara, escaping the ‘Brothers,’ Southall’s self-appointed vigilante group of moral police, and putting our characters at grave risk. The end brings a bite of suspense and danger and a big, gasp-inducing reveal.

Since being published in 2017, Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows has had mainstream success and has been critically acclaimed in literary circles and even in Hollywood (it was a part of Reese Witherspoon’s exclusive book club). The film rights have been already been snapped up, which means it won’t be long before this story is interpreted and then consumed in new and exciting ways. Whether you read the novel simply as the delicious scoop of entertainment and fun it is, or choose to look further, one thing is clear. It turns an unflinching gaze on desire, it opens up the nature of creating art, and exposes the futility of setting an expiry date on sexual pleasure. As a novel, it is as bold, unpretentious, sexy and vibrant as the erotic stories it contains.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।