Categories

During a recent conversation with an American friend who is a self-professed feminist of the second-wave variety and hence regards…

Last January, armed gunmen stormed the Paris office of the French magazine Charlie Hebdo, killing 12 and injuring 11, because…

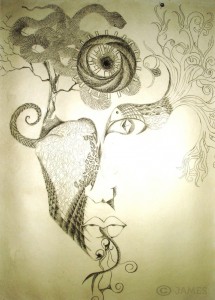

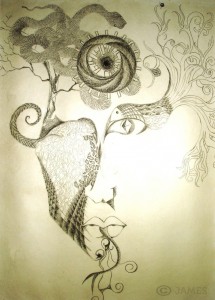

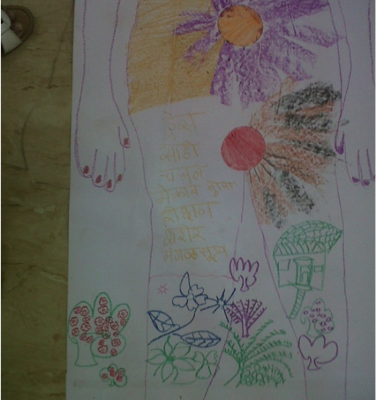

Shohini Ghosh uses examples from art history and photography as an interesting analytical tool to examine both the historical context as well as contemporary shifts in the way childhood is viewed.

Chandra Deo Singh, a name not necessarily familiar to many of us, spent time in prison in1945 for taking part…

The discursive power vested in audio-visual media can prove to be emancipatory if it seeks to re-write the scripts of love, to expand it to include various subjectivities, disturb the patriarchal gendered dynamics that it is based on by introducing a story that allows the audience to imagine it in various different ways.

The Post-2015 Development Agenda has been on everyone’s mind in the last eight months in some form or the other….

To chase down our own vulnerabilities around sexuality is a short run around the corner, five minutes ago, last night sleeping alone, with a lover, a partner who lost interest, the Insta post that leaves you feeling you’re not good enough for the hug, the kiss, the cuddle and are you perhaps the A of LGBTQIA+?

My friend recounts how, growing up, there was one object around which cohered much intrigue and darkness and which, when brought to light and consciousness through accident, (usually) provoked much commotion, commotion of outrage, disgust and fear: her (used) panties.

A long, long time ago, in a room far, far away, I remember playing at being a mythological hero I…

‘Sexuality’ and ‘marriage’ are terms that we don’t instinctively think of in the same breath.

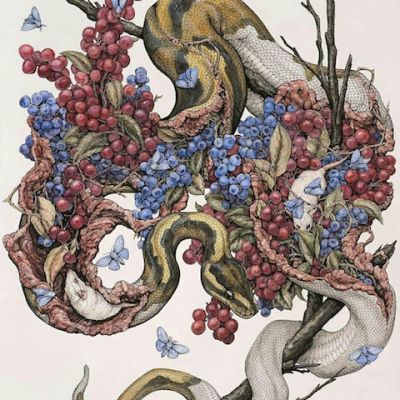

It may be useful to visualise sexual rights as a large tree with deep roots and a vast canopy of leaves. Or as a giant umbrella. Or a big tent. Whatever tickles your imagination and allows you to see it as a conceptual and practical tool to make claims for any aspect that relates to how we express sexuality.

It may be useful to visualize sexual rights as a large tree with deep roots and a vast canopy of…

It may be useful to visualize sexual rights as a large tree with deep roots and a vast canopy of…

The rabbit and the monster is a story about a baby rabbit all alone in a jungle trying to escape…

If students of such young ages can have the agency to work around hard-wired issues of sexuality and privacy, bearing in mind consent, choice and failure as part of life, we see no reason for this sense of agency to not expand one’s sense of belonging and easily create change.