Categories

Just this morning, I got an alert on my phone from an app with a grey icon that brims with seriousness; in a no-nonsense way, it announced: PMS is coming up.

Though lovers often live in their version of paradise cut off from the wider world, as far as Faiz is concerned, the world of suffering humanity intrudes. This world will intrude because at the end of the day romantic love is only one of the bonds which makes us human.

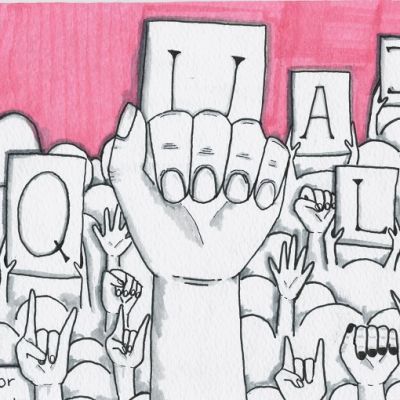

People’s movements and sexuality. There is dissonance in this. Hugging trees, protesting dams, Swadeshi and boycott, anti-apartheid, anti-psychiatry, anti-war, child rights, flags, banners and marches. What does hugging a tree have to do with sexuality? Women’s rights, gay pride, these movements are people’s movements quite regularly seen in the frame and context of sexuality. But the others?

As someone who was surrounded by the sounds of music at home from my early childhood and with a parent who worked in rural education programmes, forming connections between art and (social) change wasn’t too difficult, albeit extremely challenging to explain to many other people who didn’t necessarily see the power that art has to deliver a message or be used as a tool for change.

“Mamma, look, that’s a boy giraffe, I can see his penis,” exclaims my four-year-old daughter in delight at her discovery as we stand watching the stately animals at the fabulous Mysore Zoo. Far from cringing at the over-loud tones of my daughter, I beam at her, “That is clever of you.”

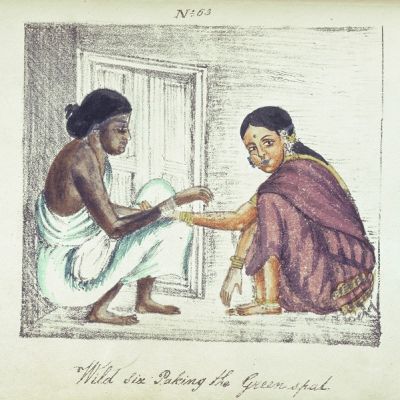

Maya Sharma is a feminist and activist who has been passionately involved in the Indian women’s movement. She has co-written Women’s Labour Rights, a book on single women’s lives. She is currently working with Vikalp Women’s Group, a grassroots organization in Baroda, Gujarat, that works with tribal women and transgender people.

TARSHI volunteer Anjora Sarangi interviews Maya about her experiences with and observations about various people’s movements in India.

Fantasy is make-believe. We make something up and then we believe it in order to make it exist. However, in some contexts, the make-believe is relegated to the realm of mere ‘play’ (as opposed to the ‘real’), but there’s no denying that make-believing is a crux of human civilisation – children naturally play make-believe games that steer them in their growth, adults use the hypothetical in their thought to make everyday decisions, and both children and adults rely on fantastical stories and myths to construct a common meaning that contributes to creating the world as we know it.

निरंतर से ऐनी और नीलिमा द्वारा यह बात लगभग दो हफ्ते पहले गाँव पठा, ललितपुर जिला, महरौनी ब्लॉक के सूचना केंद्र की…

Even in these times when sexuality is talked about more than ever before, even as we are beginning to talk about sexual pleasure and not just violations, acknowledging our fantasies isn’t easy, particularly if they are of the kind that seem to defy our politics.

Satyam Shivam Sundaram (Truth, God, Beauty) is the story of Rupa (Zeenat Aman), an archetypical abhagan (wretched girl), whose misery begins at her birth when her mother dies. She is immediately declared an accursed child and is shunned by others. Later, a freak accident results in scalding oil splashing across one side of her face, leaving her permanently scarred. Nevertheless, she goes about her daily life – alone, yet content.

Eudaimonia, ever the kind soul, made every effort to befriend her cousins who initially treated her as a pest. Maybe it was out of spite for the love Eudaimonia received from the elders in the house and that too which she often left in her wake, but before long her cousins turned their attention to her in ways so cruel, the light in Eudaimonia’s eyes began to wane and it would be a very long time before it shone through them again.

मैं एक लेखिका हूँ । बीडीएसएम (BDSM) के बारे में लिखती हूँ । एक दशक से ज़्यादा हो गया मुझे …

Dr Raj Persaud Consultant Psychiatrist Dr Jenny Bivona Clinical psychologist A team of psychologists led by a woman has uncovered some…

“The reason I chose this subject is because there’s a clear co-relation between rape and acid attacks. The patriarchy, the social stigma and the attitude towards victims are the same in both. In fact, I think the lack of empathy for acid attack survivors is ten times more because their scars are visible,” he says.

Sexual fantasies allow us to conjure up worlds that we want to play with, but in reality, we may not really want. A fantasy is different from a wish. So people may have sexual fantasies about things that they may never act out – like having sex in front of a multitude of onlookers, or with a zebra, or a famous film star or the neighbour next door. And it’s all safe.