Memory and Sexuality

In our mid-month issue we have an interesting medley of articles many of which talk about the memory of and in the body. Rashi Kapoor presents a therapist’s perspective on body memory and healing, Debanuj Das Gupta offers us a deeply personal and political insight into AIDS, melancholia and queer memory…

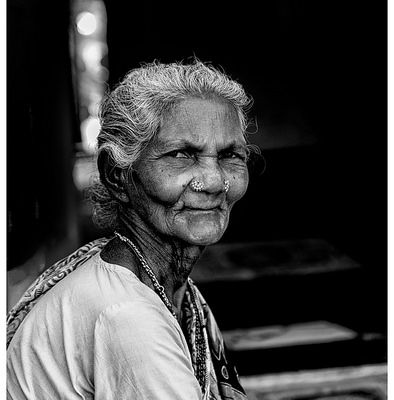

Sudha ji’s indomitable spirit made me question if I was settling down for too little, if there was more that I should ask for, and if there is more that I deserve.

“I was not a wanted child. Of course I am a girl, and that explains it. It’s like no one really cares if I exist. My brothers are useless, but they are everything to them(her parents). It’s not like he (her lover) needs me either; I still take food for him everyday.”

If not for these memories, my exploration of sexuality would perhaps have stopped a few years ago, when I was single for a long time and didn’t know if I could find someone like me.

In this essay, I revisit my early struggles with AIDS diagnosis during the summer of 2003. The recollections allow me to rethink how the New York cityscape and coming out about my HIV status to my parents in India shapes a racialised experience with HIV and AIDS, family relations, and transnational migration. Such a racialised experience is erased within Tony Kushner’s Angels in America.

चाय पीते–पीते अचानक बारिश की बूंदों की आवाज़ सुनाई दी। मैं ख़ुशी से बाहर झाकने लगी और तुमसे मैंने कहा…

A methodological approach to the study of memory and sexuality helps delineate interesting connections between the two: memory as a methodological tool for the study of sexualities, memory as an object of study, and the role of personal memory in the formation of individual sexualities.

Satya Rai Nagpaul, award winning cinematographer and FTII graduate, trans man, and trans rights activist, speaks about the influence and role of memory in his own life.

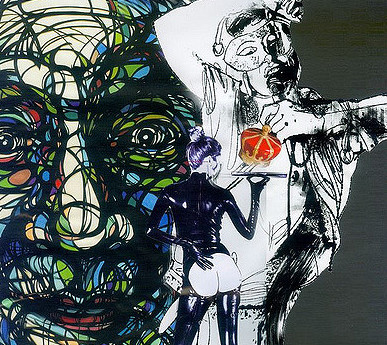

Paromitar Ek Din is a study in female subjectivity – it is essentially a woman telling the story (or rather, recollecting the story) of another woman, and reflecting upon themes of sexuality, oppression, and gender-based discrimination.

In addition to healing from sexual trauma, which took a lot of work, the most joyful part of this journey has been a discovery of my own sexuality.

Could we imagine QAMRA as an archive that is alive, and interventionist, that is enabling the creation of a new space for dialogue while assiduously documenting the lives, work and interventions of existing and older histories?

Historically, morality has been a privilege of the Savarna, and sexuality has been the fort that Savarna men seek to protect through patriarchy.

By creating a safe space to discuss these issues [of sexual abuse] and acknowledging these experiences, we can find a way to address the root cause and move forward in our healing process.

Emma Krenzer, a 19-year-old student has made waves with her art project, creating a map showing the lasting impact of human touch.