Relationships and Sexuality

आली द्वारा प्रकाशित आली द्वारा 6 राज्यों में (जिसमें उ.प्र., म.प्र., हरियाणा, महाराष्ट्र, पश्चिम बंगाल व केरल शामिल हैं) इस विषय…

मालिनी छिब के लेख सेक्सलेस इन द सिटी (जिसमें मेरी कोई गलती भी नहीं) को पढ़ना एक रुचिकर अनुभव रहा…

अब इस अनजान व्यक्ति ने कुछ बेचैनी से कहा, ‘मुझे माफ़ करना, मैं कोई मूर्ख्ताप्पूर्ण बात नहीं करना चाहता लेकिन आप को साथ देख कर इसलिए हैरान क्योंकि आप जैसे जोड़े प्राय: देखने को नहीं मिलते’। ज़ाहिर है इस वाकया के बाद एक घबराई हुई हंसी थी।

They were stranded together on an island, the only two English-speaking writers at a conference (this somehow happens in Berkeley). They have wild and instant intimacy of the kind where you tell each other everything. It’s the kind of friendship in which you want to be together all the time, the world is not enough, the day is not long enough to give you all the time you want with your friend.

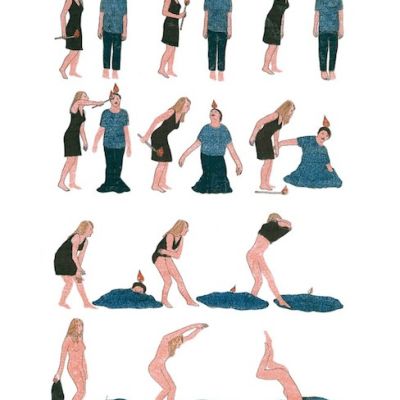

What exactly does being ‘comfortable with your sexuality’ mean? From a young age, all children, especially girls, are taught about specific ‘values’, and how we all need to behave in a certain manner or else we’re being ‘inappropriate’. However, I think the term ‘inappropriate’ simply means, “You should be ashamed of your body and should only think about concealing yourself”. And then our teachers and elders and others around us expect us to be automatically comfortable with our sexuality and with how we look, all the while trying to control us and impose their ideas on us.

Feminist critiques are often critiques of relationship structures: marriage, the joint and nuclear family, monogamy, and heteronormativity. Patriarchy, fundamentally a system of inheritance, finds a natural home in these structures.

This is why I’ve often wondered: how do feminists imagine and navigate romantic relationships? Do they have to constantly be thinking about and watching out for the many ways in which power, privilege, autonomy and entitlement manifest in their relationships and dating culture? It seems rather unromantic to do so.

Saathi IIT Bombay, an LGBTQ resource group of students and staff at IIT Bombay welcomed new entrants in 2015 with…

While the video’s message of women finding self-worth through beauty can be construed as sexist (our worth can’t be reduced to mere beauty and looks), and it also has the token ‘fat’ woman that one can criticise it for, one also can’t deny that the loving and acceptance of one’s body remains a universal, daily struggle of probably every woman the world over.

Mainstream media is beginning to pay attention to men’s relationship with abortion – a welcome counterpoint to the anti-woman, anti-abortion rhetoric Men’s Rights Activists (MRAs) spew on the topic.

“Order me one too,” a friend said as I secretly purchased a vibrator online during a class so boring, I…

“Only that once again they broke the Love Laws. That lay down who should be loved. And how. And how…

A multitude of views are recorded when couples are interviewed about their sex lives and relationships. It is often found that while women are more concerned about the way they look and how they react to their partners’ moves (including women’s need to fake orgasms), men worry more about things like performance. It is safe to assume that all of us have sexual insecurities.

So, what can be done about insecurity?

Is there a relationship at all that cannot be defined by love? And, if we were to begin talking of relationships other than romantic love, how would we speak of sexuality? Upon this deliberation, we realised that our Love and Sexuality issue seemed to revolve around romantic love and sex. The departure this issue on Relationships and Sexuality makes is to try and incorporate forms of relationships that might not be about romantic love but have their own kind of romance, and facets of sexuality that might not be about sex per se but will place its interest in alternate relationships to it.

True were his words that people will always talk, but why? What was so wrong with us? Was it because he was shorter and I was taller? Or was it because that when we hugged he was more in my embrace than me in his? Or was it that I had to bend a bit to kiss him? Strange how perceptions work about couples – no matter which identity one conforms to.