Review

Indian films have for long fed into as well as mirrored social and cultural practices. Many of them depict a woman as being restricted to the kitchen and serving delicacies during festivities.

The first sensations that we experience are related to and derived from our body. It is a site of experience, expression and contemplation. The body is a means of voicing our deepest realisations, but how others visualise it can be a source of intense pain.

It is unusual to find films that focus on older people, especially women, given our obsession with youth, ‘fit’ bodies and beautiful faces.

No Limits explores several themes – the struggles that athletes go through to reach their goals, the personal and professional risks they take to break records, the compromises they make and the single-minded focus required of them.

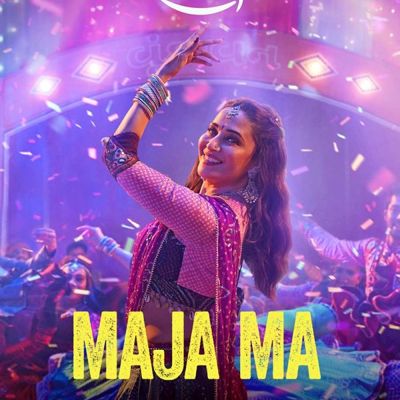

This reconciliation between Pallavi’s public (seemingly) heterosexual and closeted lesbian identities points to a distinctly Indian way of avoiding polarities through a new social arrangement where both identities are allowed the space to flourish.

Sam is an 18-year-old boy who believes that he is ready to have a girlfriend. He is on the autistic…

Reviewing three films (or the subplots of three films) to see how subplots show that marriage isn’t a destination or a single story that begins and ends in the ‘happily ever after’.

In a world where queerness is looked at as failure, The Queer Art of Failure allows for many possibilities to make sense of these failures.

The Half of It is beautiful because it brings out the insecurities of teenagers who want to fit in with the world around them and are confused about their feelings which might be the diametrical opposite of what is socially expected.

This film reminds us of the power of connections in finding pleasure, joy, confidence and healing.

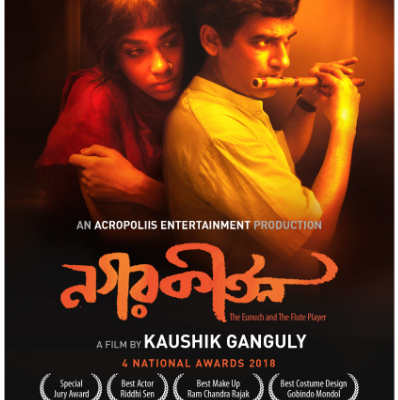

The film has all the makings and trimmings of a commercial thriller – a dynamic story, song and dance, an action-packed climax – and at the same time, it is a cinephile’s film.

The plot of the movie narrates the tale of the love that grows between two people who are struggling to survive in a world of rootlessness and are continuing to make a cosy home for themselves. The love between Madhu, who works as a food delivery boy, and Puti, who survives by singing at traffic signals, blossoms while they cross paths everyday at the traffic signal and the look that they exchange appears to us as if each of them is trying to find a home in the other.

In theory, the concept of the app is a great one – it provides women, queer people, and people belonging to oppressed castes the tea-stall, cigarette-shop type of public spaces for conversation that are available to upper-caste cis het men. The relative anonymity acts like a safe cover, and the app affords a certain autonomy and agency to marginalised people to regulate the kind of conversation that goes on in rooms moderated by them.

Nathicharami takes sexuality and sexual desire away from upper-class, Gucci-clad women and makes its viewers acknowledge its existence in the lives of women (middle-class wives and widows, in the case of this film) who are invisibilised, both in the society they live in and as subjects of popular content.