Review

No two human bodies are alike, and our different bodies arouse curiosity. But our fascination for the aesthetics of the perfect human body has historically created a space within art, science and religion for the examination of the ‘abnormal’ and the ‘imperfect’. As a result, some bodies are normalised while others become oddities. Freak Shows, and to a large extent, circuses and even exhibits in medical or anthropological museums particularly stand out for dehumanising and objectifying these different anatomies, and oftentimes subjecting these bodies to violence and discrimination.

The Church says: the body is a sin Science says: the body is a machine Advertising says: the body is…

The Church says: the body is a sin Science says: the body is a machine Advertising says: the body is…

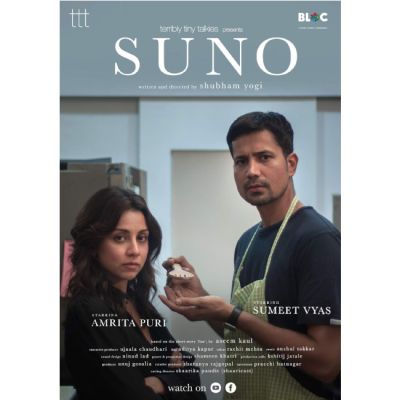

There may be situations in which a person’s responses might not be unquestionably equated with consent. Is consent merely a ‘yes’ or does one need to look for other cues to make sure their partner wants the same thing as them when it comes to intimacy?

The movie was criticised for its stereotypical portrayal of Debu as a gay man. But, the beauty is that it also highlights the reversal of gender roles. The smiles, and the laughter sounding throughout the house, create a cheery note in the movie.

Every Friday my organisation Red Dot Foundation hosts a SafeCircle, an online space for listening and for sharing experiences of…

In the spirit of the Games, I watched the Netflix film Rising Phoenix which documents the history of the Paralympics and its impact on the world in making visible the topic of disability. It also tracks the personal and professional journey of some of the top Paralympic athletes who share their challenges, frustrations and motivations.

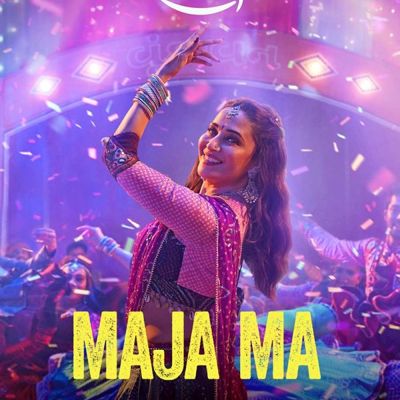

Indian films have for long fed into as well as mirrored social and cultural practices. Many of them depict a woman as being restricted to the kitchen and serving delicacies during festivities.

No Limits explores several themes – the struggles that athletes go through to reach their goals, the personal and professional risks they take to break records, the compromises they make and the single-minded focus required of them.

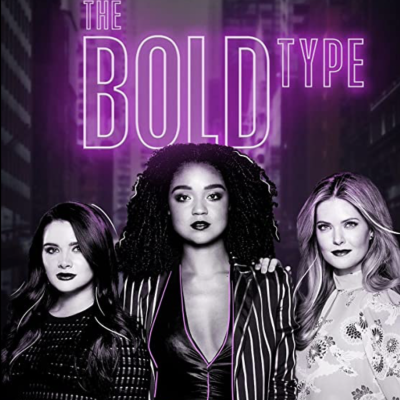

None of these characters is perfect but in their imperfections we can learn more about body positivity, gender sensitivity, privilege, consent, unconscious and implicit bias, sexuality, masculinity, their intersections with class, religion, race, age, and more.

Reviewing three films (or the subplots of three films) to see how subplots show that marriage isn’t a destination or a single story that begins and ends in the ‘happily ever after’.

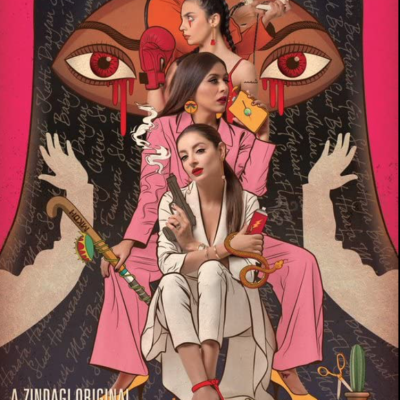

Their inimitable personalities showcase their varied conceptions of insaaf (justice), enriching and intensifying the plot and, at the same time, reaffirming their solidarity and strengthening their unity.

By and large, society expects a woman to marry. Often people in one’s circle judge a woman if she doesn’t marry, inquiring about what could be wrong but most never assuming that it could be out of choice

This reconciliation between Pallavi’s public (seemingly) heterosexual and closeted lesbian identities points to a distinctly Indian way of avoiding polarities through a new social arrangement where both identities are allowed the space to flourish.

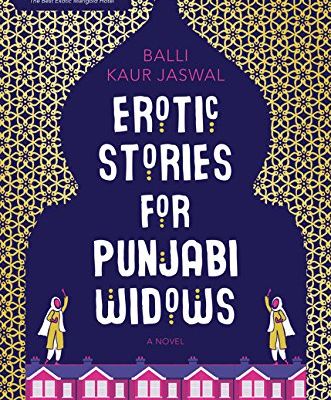

The story is so well told and is written with such a light, deft hand that it is almost easy to miss what makes it so quietly radical. To review it within the scope of exploring the coming together of literature and sexuality we must begin with its central cast of characters – the widows.