Voices

We need to claim our spirituality differently and imaginatively. There are many paths to god. For some it might be religion, or science, or sex, or love, or meditation, or art.

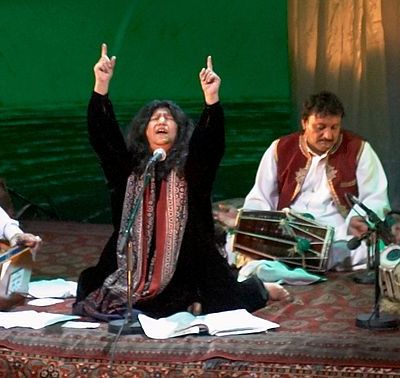

Sounds of Abida Parveen and Falguni Pathak’s force move me to other frames, that foreground unforgiven settlements. They provide me with what Jacqui Alexander has so beautifully called “pedagogies of the sacred.”

However elusive the combination of safety and adventure, it’s a framework I find terribly useful. It helps me understand much of life, including spirituality and sexuality, and what the two might have in common.

Or is spirituality something larger, existing in itself, a consciousness much larger than sex, with sexuality being a smaller part, one that is bound to the body, a physical act of pleasure in the temporariness of time and space expressed through the body which is a limited instrument for it?

As these correlations between gender development, physical violence and mass shootings come into sharper relief, the term “toxic masculinity” has become a staple of public discourse used to characterise men like Connor Betts, and even Sandeep Singh.

The social contract of family becomes the sexual contract of the state, i.e. by placing women within the ‘domestic space’ under the ‘control’ of the ‘right’ kind of men. During partition this played out in the ‘reclaiming’ of the ‘abducted women’.

The use of terms that convert the movement for women’s empowerment into extreme militancy in order to reject the movement altogether is indeed a sombre example of diverting attention from the real problems that exist in society and projecting women’s protests against sexual crimes or standing up for their rights as one of “mob lynchings” or wrongly adducing the news of repealing “Adultery” as a move that allows women to have sexual relations outside of marriage.

This immense pressure to perform masculinity throughout each day and night not only impacts men’s wellbeing, but it also inevitably impacts the way they interact with the world around them. These interactions – this performance of control over oneself and others – reinforce the social norms and norms of power that drive gender inequality.

Social norms don’t expect women to look muscular, but if men are muscular, it is considered sexy. Just by choosing to pursue a largely male-dominated sport that glorifies what is accepted as “masculine”, Karuna and Sibalika are pushing the boundaries of these labels.

This malignancy of toxic masculinity is a mutant inheritance that is hard to eradicate. However, initiating discussions about it and spreading awareness is essential to minimise the cost to its victims.

In a patriarchal society, masculinities manifest or show-up as a very particular set of behaviours such as being controlling and dominating, often in violent ways. In fact, the root of masculinities in a patriarchal society emphasises practicing this violence and control.

There is someone in my life who had a terrible childhood, has had several liaisons and whose father married twice. He says that he hated his father. How would his father react to his son’s liaisons if he were alive? If I love a cyborg or a person of the same gender, how will my father react?

Traditional masculinity is not without its problems but to eliminate its component of stoicism is to pull the rug from under a cast of tough and determined characters who make society function.

One summer afternoon some moons ago, a man at work assigned to help me move numbers on an excel sheet…

In a society that restricts one’s expression of sexuality and perpetuates patriarchal gender norms, there is little room offered for open exploration. With no Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE) in schools and no conversation about sexuality with parents, children are ill-equipped to navigate their puberty as adolescents, and dating and relationships as young adults.