When I first started working at 23, fresh out of university, in a tier-2 city, I was scared but resolute that I wouldn’t let my queer identity get in the way. So, I decided to leave that bit out whenever I talked about myself. Stuck in an unfamiliar new city, with no friends, in a double-sharing room with no space to express myself on my own terms. At work, I feared that if I was ‘found’ to be queer it would be an inseparable association – I would be boxed and labelled. Any mistake I would make would be attributed to my being queer. Most of the organisations where I had interned during my bachelor’s had a strong cis-woman anchoring the project which somehow made me comfortable to engage, even without revealing that I was queer. I was discussing this feeling of having been comfortable in those places with a friend, and she said it was probably because most of these women had feminist ideals at the core of their thinking. But this organisation was led by a cis-man who would never even acknowledge feminism that way. This led me to choose silence and safety. To not be out and blend in the environment that I was in. I chose to never come out to anyone here and to pass off as a ‘straight, cis-woman’.

A strong boundary between my personal and professional life is what allowed me to function in this dissonance. I would never let my two worlds collide. The office culture encouraged sharing, talking about your life, even gossiping maybe. However, this encouragement did not guarantee my safety, making me more sceptical of it. I’d often quietly observe how, time and time again, other people’s stories and insecurities were turned into lunch-table jokes which made it worse for me to engage with them.

While I carefully rehearsed what to say, what not to say and how to deflect questions on my personal life, others freely spoke about their lives – marriage, kids, children, families. I was expected to do the same. My silence made me somewhat of a mystery to crack and drew more attention. From what I could tell, I was already clocked as ‘different’ because of my ‘not-quite-femme’ presentation.

There was a constant push to form friendships within the small team. “We spend nine hours in the office, how do you expect to have a clear boundary of personal and professional. These are all your friends and colleagues”, I was told.

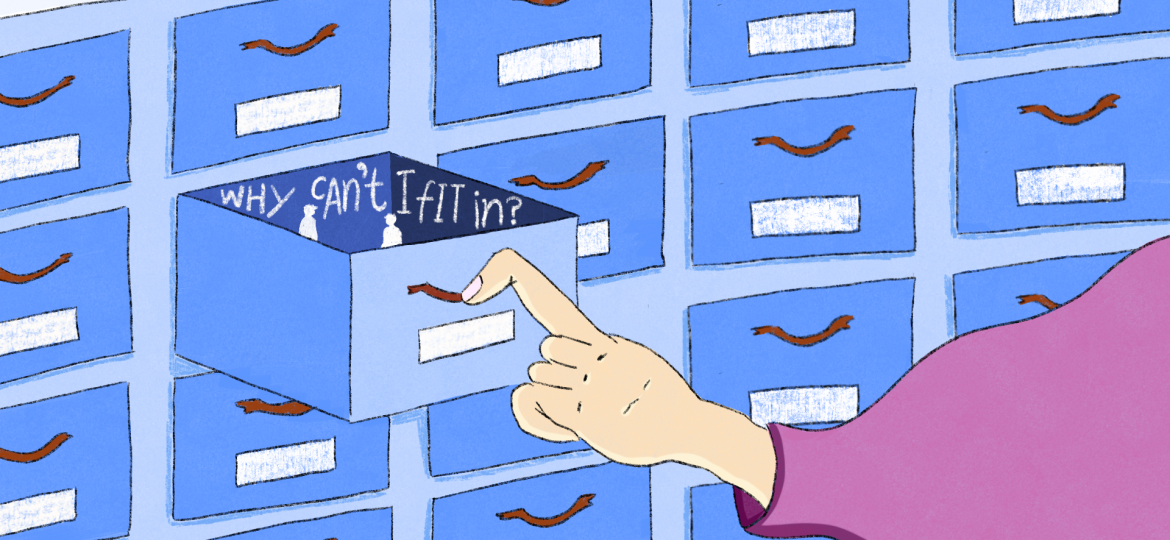

I vehemently disagreed and made a mental note to only engage as much as necessary. But I saw how easily cis-het people could fit in. They had nothing to hide, nothing to fear – no past shame or trauma tied to their existence. Nothing about their lives was once illegal, there was barely any question on their being. Nothing about them unsettled the heteropatriarchal fabric of the workplace, or society at large. They belonged. I didn’t.

A few months in, one of my colleagues discovered me on X, where I am vocal about my queerness. While he probably wanted to show support and be kind about it, much of what he said after “I found you on X, queering and all, hanh?” is a blur in my brain. Mostly because of how anxious I felt hearing these words come out of his mouth. I was advised to bring it up in the office – to be open about it – because I would be understood and included. But the idea of being discovered rather than choosing to come out, itself felt intrusive. I felt like I was robbed of my agency and personhood and had lost the ability to make the decision to come out on my own terms. I don’t know what my colleague’s intentions were or whether his advice was really out of kindness, because my paranoia and anxiety left no space for me to process or engage with it. Queerness, a very huge part of my being, was already something I was running away from, and here I was being asked about it and feeling this immense shame for being ‘seen’. My fear that I would not be seen for my work but for my gender and sexual identity was all I could think of. Why did my queerness need to be a topic of office conversation? How could I trust the people whose imaginations of love were so different from mine? I was highly sceptical of their ability to engage with same-sex love when they could barely confront everyday sexism.

Around the same time, there were discussions about co-designing a DE&I policy for the workplace. I did not see a point beyond tokenism. The same people who casually ridiculed each other, made sexist and homophobic comments about each other would suddenly keep kindness at the core of their engagement with one another? Absolutely not. Such changes take place over long periods of constant engagement. Safe spaces don’t simply exist; they are created by rethinking the whole structure within which a toxic workplace operates. There was barely any evidence for me to trust them because their actions spoke louder every time. I had no energy left to hope for acceptance.

I don’t know what a counterfactual version of this experience would look like – one where I openly communicated that I was queer – because it doesn’t exist. Every time I work outside of academic spaces, the threat looms over me. Each time, I choose to hide, to blend in, afraid of what will happen if they find me on the Internet or ask for my social media handles. When is the right time to come out? Is it after I’ve made a place for myself? Why do straight people never have to think about this? Why do I constantly have to carry this anxiety?

….

What does a queer-friendly workspace mean to me? Honestly, I don’t even know because it’s a question that’s been haunting me for sometime, and I’m not sure if I’ll ever find the answer to it. We never know, maybe the perfect queer friendly workspace doesn’t even exist. Even though I’ve been mostly out and vocal about some parts of my identity at work, I can’t say I’ve ever felt completely, unquestionably accepted in these spaces. It seems very complicated, and I feel the answer is never just a simple yes or no.

In the past this whole idea about being accepted in a workplace used to hit me the hardest whenever I would apply for new jobs or sit nervously through interviews. Anything that required verification/documentation work for proof of identity would stress me out. Not that I’ve been to hundreds of them, but after working for six years (started working at eighteen), I’ve seen my fair share of awkward conversations that I encountered at these spaces, especially in terms of identity negotiations. It all began when I was in the second year of my bachelor’s, stuck back in my hometown, in the middle of the pandemic. Back then, choices were limited for me – I had to say yes to pretty much any offer I came across, whether it was paid or not. This happened to an extent that I ended up juggling three or four part-time gigs at once – corporates, collectives, personal projects – all remotely.

It wasn’t until much later that I got to meet people from these workplaces in person when the second wave of COVID-19 was ending. Much of it is a blur, but I remember being the youngest queer person in the room. It is not as cool as it sounds. I was working as a designer at a small start-up when I was in the middle of figuring out how I identify. They used to act all-inclusive and open to having me, a young GenZ on their team, and what not. During meetings, they would keep misgendering me (in Hindi) and it would trigger my dysphoria around my body and identity. So, one day, I gathered all my courage and told my senior that I would prefer to be referred to in neutral ways.

It was my third month in this organisation when I decided I needed to be called by my preferred name and pronouns, even though they weren’t officially registered. This came with its own issues and headaches. Whenever someone new joined the team, I was expected by my bosses to give a crash course on my identity – why my name is so short, what non-binary means, and why I use they/them pronouns. People raised eyebrows. I explained, then I explained some more. A month or two in, I started getting irritated with this tokenistic behaviour of my bosses.

My colleagues kept putting me forward like some kind of proof that they were accepting and respectful, but their behaviour didn’t match because I could sense the mockery in their tone. A few of them who were in their early and late 30s used to take me out and ask, “Who are you into? Why don’t you like men? Have you ever tried?” Sometimes comments like these used to be made too, “I feel I am bisexual too, you know I do find women pretty.” It all felt very intrusive. I realised that in places where I wasn’t as open, I was actually more at ease. I started thinking –maybe I shouldn’t have said anything at all. During multiple instances I had witnessed people at the office talking about other people’s vulnerabilities and laughing about them. I would often actively choose to avoid these people so that I didn’t become a laughing stock. I didn’t want my queerness to be a topic of gossip for them. I was also considered a bit amusing to them maybe. But I was dispensable for them, the ‘youngest, junior-most queer employee’. I couldn’t do much and I found myself being constantly in the cycle of placating them and feeding their egos, fearing expulsion. So, I never called them out and told them how I felt about it all.

I feel this is where we see how rights on paper don’t guarantee equality and prohibit discrimination. Heterosexism and homophobia still thrive in subtle and not-so-subtle ways in many professional environments. Workplaces, in theory, should be safe spaces that uphold the dignity of their employees, respect their personal decisions and other aspects of their personal expression. But in reality, what I experienced is that these spaces often demand queer individuals to constantly educate, explain, and justify their existence. After finishing my Bachelor’s degree and moving to a new city for my Master’s, I promised myself to not engage much in conversations with people around my gender identity and sexuality. To my surprise, however, I found an altogether different culture in my college that gave me the strength to openly accept and talk about my queerness.

Two years down the line, I have a Master’s degree and currently I work as a freelancer. The freelancing life gives me the privilege to choose who I work with, but the media world is not that open-minded. I decided to be a little less open about my personal life in workspaces. One time, I asked a senior colleague to use my preferred name for my email ID. He didn’t exactly refuse, but his response had this sassy tone that sounded a bit dismissive. Later that week, in a group meeting, when I was being introduced to the team, he announced my queer identity and casually mentioned that he didn’t agree with they/them pronouns. “I don’t have a problem with your identity and things you shared,” he said, “but these new pronouns and trends kind of mess with English grammar structure and I find it quite difficult to follow.” I thought to myself, “How is that an excuse even, like it doesn’t sit well with him, because it’s not about him?” His lack of empathy appalled me.

Since then, I’ve become his little token. Whenever someone new joins, he announces my identity and then takes a dig at my pronouns like it’s breaking news. It has happened so many times that I have his script memorised in my head. One day I went out for lunch with him and a new person whom I started reporting to later, and the conversation around social media came up. This new person asked if I used Instagram. That’s a hard No for me – sharing personal accounts with work people is just not on the table. She kept pestering me and asking how I existed in today’s time without using social media. I kept refuting it and she went on and said, “Don’t you need it, you work in the social media front.” I was baffled because if I need it, why is that a discussion for all of you? I was so frustrated that I just went on and said, “I use a Finsta to just be updated but I have no active social media life.” Was that it though? The moment I said that I realised that in these heterosexist spaces where bonding often happens online, I feel like I’m always a step behind.

More than all these small or sometimes big negotiations, what often goes unspoken is the emotional toll of navigating these situations. It’s not just about pronouns or a social media request – it’s about the constant pressure these situations build on a person where they have to decide in a split second whether to assert their identity and be seen and respected for who they are, or to save that energy of explaining and to live in the shadows of their own resentment for making this choice. Even in supposedly inclusive spaces, there’s a pervasive undercurrent that asks queer individuals to conform, or else to shrink parts of themselves. For me personally, the psychological weight of this is enormous and puts me under pressure where it becomes extremely difficult for me to even know how to present and express myself.

Navigating workspaces as a queer person is messy. Sure, we have constitutional rights and HR handbooks that state the ocean of rights for employees, but heterosexism and homophobia still show up in ways that drain queer individuals. We need more than just tolerance; we need spaces where we can show up fully without having to explain or defend who we are. We need policies that aren’t just performative, but actively foster respect and understanding. And we need allies who don’t just accept us to gather tokens but actively challenge the status quo and create inclusive and less intrusive spaces.

…

Two of us have written this article together. One of us identifies as non-binary, queer and prefers to not talk about our identity at work, and the other is, more often than not, vocal about their identity and preferences in terms of how they want to be referred to and identified. Regardless, when both of us speak about the way we engage in our workspaces, we find common contradictions and barriers. How does a queer person navigate these barriers, constantly negotiating when, where and on what terms to engage? To be seen or to remain unseen? What does safety, belonging and inclusion look like in professional spaces? These are the constant questions that haunt us as we continue to figure out what ‘belonging’ means for each of us in these spaces. Or, if it even really exists for people like us.

Illustrated by Niv