Despite the pandemic, the Tokyo Olympic and Paralympic Games are going ahead, albeit one year behind schedule. ‘United by Emotion’ is the theme and it is really apt because we can all do with some inspiration. The Sports Authority of India sent me a Team India jersey and invited me to send a message of encouragement to our athletes: 24 Paralympic athletes and 119 Olympic athletes. As I recorded the message, I was filled with a lot of emotion because these athletes have trained for years for this moment in the sun and unfortunately, this year, they will not be accompanied by family, friends, and fans. Nevertheless, it is the largest sporting event in the world and everyone will be cheering the participants on, including me.

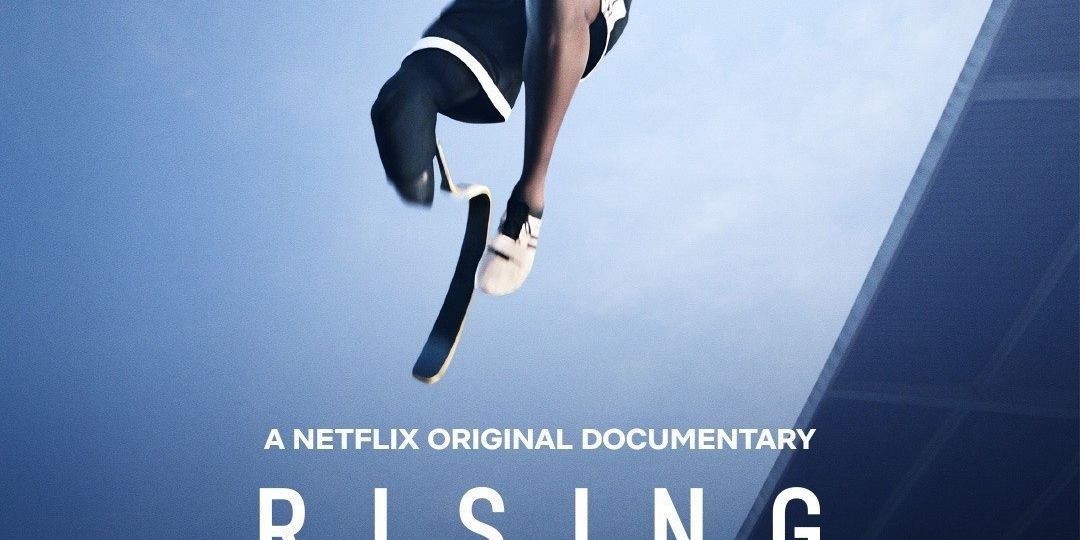

In the spirit of the Games, I watched the Netflix film Rising Phoenix which documents the history of the Paralympics and its impact on the world in making visible the topic of disability. It also tracks the personal and professional journey of some of the top Paralympic athletes who share their challenges, frustrations and motivations. These stories (some of which I will briefly recount below) resonate with us because they are people with needs, fears, aspirations and want to be loved for who they are and not be pitied for a part of their body that is missing. Through these inspirational stories we see how, despite the odds, these people have achieved extraordinary feats. Sport is the unifying factor that helps them achieve their potential. It also provides them with an identity in a world where disability is looked down upon and not taken into consideration when designing systems, policies and infrastructure.

The founder of the Paralympics is Dr Ludwig Guttman, who was head of the Stoke Mandeville Hospital’s Spinal Injuries Unit and believed that movement was essential for the recovery of patients of his who had lost mobility, especially those with spinal injuries. Apart from having their bodies gently turned in their beds every two hours, he also played simple ball games, wheelchair polo, basketball, archery, and darts with them. He found that playing these games strengthened his patients’ bodies and they lived, thrived, and were motivated to excel. Thus was born the Stoke-Mandeville Games for the Paralyzed which was held on the sidelines of the 1948 London Olympics, the first Olympic Games to be held post World War II. 14 men and 2 women participated in archery, the one sport played in the Games. This evolved into the Paralympic Games, first held in 1960 in Rome, which saw 400 athletes from 23 countries participate. Unlike what people might infer, ‘Paralympics’ stands for parallel to the Olympics and does not mean ‘for the paralysed’.

The Paralympic Games reached a high point during the 2012 London Olympics under the leadership of Sir Philip Craven, President of the International Paralympic Committee. As a former wheelchair basketball player, he was passionate about creating greater opportunities for people with disabilities and to change how society in general perceived disability and persons with disabilities. He led a campaign to highlight the disability rights movement as he believed it was a very short window to put the spotlight on disability in the Paralympic Games. As part of the publicity leading up to the London Paralympics, at the end of the Olympic Games that preceded it, billboards were put up all across the city saying “Thank you for the warm-up”, a cheeky bid to hint that the Paralympics were the ‘real thing’ as well as a bold stance given that hate crimes against persons with disabilities were at an all-time high. Many people did not think that the Paralympics was really a sporting event. But the Games show how athletes with disabilities can achieve extraordinary goals even if the people around them think they cannot.

As one unnamed para-athlete says in the film, “We are all superheroes because we have all experienced tragedy. We have all lived through something that did not allow us to succeed. And that’s where our strength lies.”

It is incredible to hear these stories as these athletes were told time and time again that a fulfilling life was going to be impossible for them. They were bullied and harassed but they found motivation in and from sport, have thrived through sheer self-belief and resilience, and have inspired many. As seen in London, the stadia were full of people cheering them on and it is a great way to open one’s eyes to the beauty and strength of the human body and mind.

In the Olympics, we marvel at the physical tone and fitness of the human body. It has always been about celebrating the ‘perfect’ body, one that is non-disabled and hetero-patriarchally perceived. But in the Paralympics, no two bodies are the same. Some are born with a disability and some acquire one either through an accident, a medical illness or even war. Even in the same sporting event, no two athletes are physically alike. But that does not stop the athletes from competing for a fair chance at a medal. They train hard and give the competition their best shot.

Australian swimming champion Ellie Cole said that if her parents had seen the Paralympics when she was three years old, they would have had more hope in what people with disabilities can do. She was born a healthy child but had a rare form of cancer that led to her leg being amputated when she was three. Her parents didn’t know anyone with a disability and were worried for their daughter. Ellie wanted to be a ballerina after she watched Swan Lake and was inspired to use water as a medium to be fluid and light-footed. She also wanted to be the fastest kid on the squad. She is now considered one of the most graceful swimmers on the Australian swimming team.

Bebe Vio is an Italian wheelchair fencer who always dreamed of winning a medal at the Olympics. She fell in love with fencing at the age of five and went on to become a champion at it for six years. At the age of eleven, she almost lost her life to meningitis. She was in a coma, and to save her life, the doctors amputated her arms from the forearms and her legs from the knees. She didn’t know how she was going to live as she had to relearn all movement, including brushing her teeth. Fencing, once again, came to her rescue and gave her the motivation to live. She constantly questioned why she was in this situation as she had never done anything ‘wrong’. But being the champion that she is, her winning mindset helped her focus. She says, “Your mind needs to be clear”. She went on to win the gold in the 2016 Rio Paralympics.

Long-jumper and runner Jean Baptiste Alaize had a traumatic childhood wherein he survived the Burundi Civil War, between the Hutus and the Tutsis. He was fleeing his village with his mother when they got caught up in the fighting. The perpetrators chopped off his leg with a machete and he was forced to watch his mother being killed. Subsequently, he had to rebuild his life as an orphan with a disability. He was later taken to France where he was bullied because of his race and his disability. He was extremely lonely. He says, “I run to escape” and “Sport is what saved me”.

Matt Stutzman is a North American archer who was, medically inexplicably, born without arms and uses his feet as hands. Very early on, he discovered that he loves driving. He says the car does not stereotype the driver as it just wants to be driven. Similarly he believes that the archery bow just wants to be shot. He was adopted by a family who helped him adapt to the world and told him that the world was not going to adapt to him. They encouraged him to try new things, gave him the space to thrive and figure out solutions. As a result, he has driven cars, climbed trees and even ridden a bull.

Tatyana McFadden was born in Russia with spina bifida that left her paralysed from the waist down. She was placed in an orphanage that, unfortunately, could not afford a wheelchair and she would scoot around using her upper body. She was adopted at the age of six by North American parents. Her well-developed upper-body musculature came in handy when she took up wheelchair racing. When her college didn’t allow her to be part of their sports programmes or use related facilities, she filed a case against them fighting for the right of people with disabilities to be included. This led to a federal law, the Sports and Fitness Equity Act, being passed, which is popularly known as Tatyana’s Law. When she wanted to compete in the Russian winter Paralympics, she picked up a new sport – downhill skiing. Although her coaches told her that she should focus on her summer sport and not try something new, she went on to pick up a silver medal with her birth mother and adoptive parents by her side.

The film has so many inspiring stories of how athletes with disabilities have overcome many odds to do incredible things. Prince Harry, Duke of Sussex who is a great supporter of the Paralympics rightly says that no amount of teaching in schools or reading in books can give you the inspiration like watching what the athletes achieve despite people having told them it is impossible. Sport is the hook that brings you back to life.

However the Paralympics almost didn’t happen at the 2016 Rio Olympics when the organising committee informed everyone that they had run out of money and could no longer host the Games. This was extremely demotivating to the athletes, who felt hurt that the budget meant for their Games had been used for the main Olympics, driving home the marginalisations they face on the basis of disability It was because of sheer determination and lobbying by the Paralympic Committee that the Games took place. Had the Games not taken place, the disability rights movement would have faced a setback as confidence would have been broken. So it is important that the games continue at the Tokyo Olympics.

The Paralympics make heroes. The athletes’ indomitable spirit is infectious. As Sir Philip Craven says, “Give us a chance. If not, we will make our own chances. The Games will go on.” These stories certainly invite us to challenge not only our implicit bias about disability but also socio-cultural norms that exclude people who do not have the ‘perfect’ bodies from competing. Remember, there was a time when black athletes and women were not welcomed at the games and same-sex desiring people were frowned upon.

History has shown us that not always have para-athletes been welcomed and supported. At the Atlanta Olympics they were not treated with dignity whilst Moscow refused to host them in 1980 with one official saying, “There are no invalids in the U.S.S.R.!” Our own para-athletes have been subjected to a lack of basic infrastructure like wheelchair access and other facilities at the qualification event for the Paralympics. North-American deaf-blind swimmer Becca Meyers recently announced she was withdrawing from the games because she was not allowed to take her Personal Care Assistant (PCA) who is essential for her to successfully compete in the sport. To restrict the number of support staff due to safety measures around COVID-19, the US Olympic and Paralympic Committee told her that she along with 33 other Paralympic swimmers could use the services of the one PCA available to assist them. These examples show that to create an equitable playing field, the needs of each of these players must be taken into account. Anything less would be non-inclusive and literally keep them out of the game.

Sport is a unifying factor and we can definitely do better to ensure that we invest in infrastructure and change societal attitudes so that we truly include people with disabilities in all aspects of life including in the Olympics. I certainly will be wearing my Team India jersey and cheering them on.

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।