Among the many criticisms of porn regurgitated ad nauseum is its supposed educative function. Coaching men on how to dominate, oppress and objectify women. Training women on how much hair to shave and how many “Oh god, oh gods” constitute a believable orgasm.

While we’ve grown used to hearing porn blamed for society’s ills, it’s now the medium’s comparatively matronly cousin – romance novels – that have come under scrutiny.

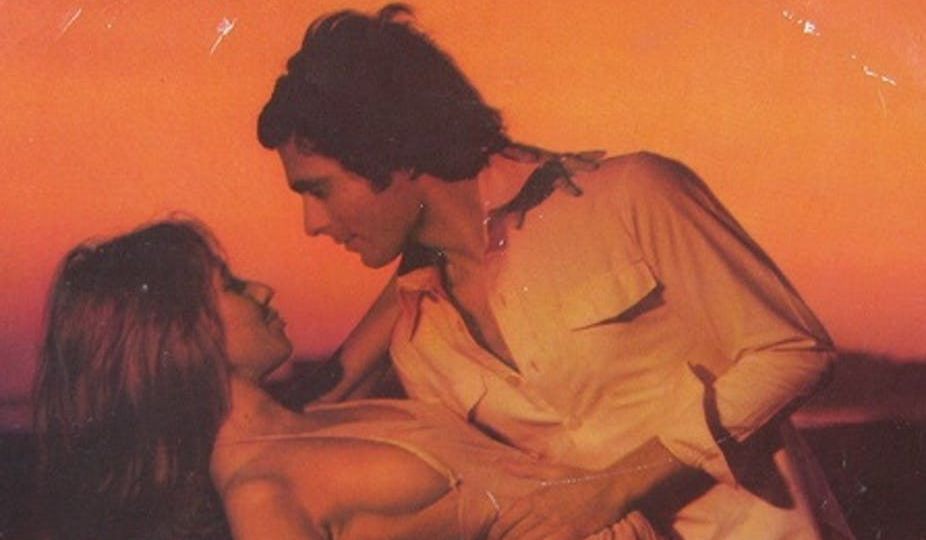

You know the ones: the paperbacks with the greased-up Fabios and the comely maidens, breasts straining their corset seams.

Susan Quilliam, drawing on her work at a family planning clinic, contends that these novels sabotage the work of clinics; that the love romps mess with the impressionable minds of female clients leading them to dodgy health choices.

Women overcome by male seducers. Men leading women to uncover the lust in their loins. Love conquering all. Love laughing at condom use. False promises of firework-orgasms.

Problematic messages about consent and desire, protection and expectation.

Quilliam makes some very interesting points. Points, of course, that are equally applicable to romantic comedies. And to advertising. And to porn. And to pop music. And to literature. And to …

Our pop culture is full of representations of love and sex and relationships. Without them our bookshelves, our cinemas and our iTunes libraries would be very sparse indeed.

Pop culture, however, is also full of other representations.

Many contemporary talking heads, both the academic and the journalistic, keep vomiting out claims that people – predominantly women – are cultural dupes.

That we are merely lay-back-and-take-me saps who think that if we read it between the covers of Mills and Boon, not only must it be true, but that it’s also prescriptive, instructional, mandatory.

When commentators speculate on the influence of porn, of romance novels, of advertising, strategically forgotten is the fact that nobody ever gets just one media message.

No woman lives in a bubble with only a Harlequin romance novel for company and no man resides in a vacuum with just his stack of Hustlers.

Some commentators – strangely and suspiciously enough – seem convinced they can prove what decades of media research has failed to do: establish, without a shadow of a doubt, a cause-and-effect relationship between media consumption and audience action.

Of course, the one thing that weakens these arguments – which weakens all arguments about the supposedly great and powerful influence of the media – is lived reality.

A lived reality where we each get an infinite number of vastly different messages from all-over-the-shop sources.

Along with competing media messages are people. Those who teach us and who are taught by us, and who share our offices and our kitchen tables and our trams.

Those people we love and admire and elect to spend time with, and who also each serve as conduits for information and values.

It is thoroughly perplexing to me that anyone could dare postulate that a romance novel is somehow more influential, more educative, than the lived experiences of the real women around us.

The women we interact with personally who have aborted unwanted pregnancies, who have been sexually abused, who are sharing beds with selfish lovers.

Women, whose stories weigh more heavily on our shoulders and in our hearts than any bodice-ripping yarn.

There seems to be a cultural preoccupation with devising ways to academically justify the denigration of certain media products.

Be it products considered low-brow, in poor taste or which, God forbid, lead to arousal, there seems to be an obsession with justifying why these items are bad. A fixation on making us feel wretched, feel guilty, feel stupid for enjoying them.

Knowing that people have little tolerance for arguments grounded in morals dictated from on high, wowsers and thought police are busy concocting ever newer ways to harangue us about what we should and shouldn’t read and watch and masturbate to. Arguing that they provide false information is a mere example.

I don’t doubt for a moment that romance novels provide problematic information about sex.

But to pretend that the only message, or even just the strongest message received comes from steamy paperbacks is simplistic at best and conservatively deceptive at worst.

This article was originally published here.