She loves clothes! She has more than she needs and more than she can count, and yet she feels she has not a single thing to wear when she has to go out for a special occasion.

Having been brought up in a family that appreciates dressing up, her fancy for clothes was never seen as an indulgence. Her mother’s trademark big bindi and cotton saris have always been in place any time of the day, whether she was cooking, was out in the sun or rain, was asleep, had just woken up, was smiling, or crying. Her mother’s fashion tip to her and her sister was, “Always dress up as if you are going out, even if you are at home.” Despite her mother’s advice, she turned out to be of the ‘ragbag at home and Cinderella when out’ variety.

Coming from a small town in South India, her younger days in school and college saw her dolled up in a half-sari or a sari. Her Sanskritised college had a compulsory dress code: Half sari or Sari. As if that were much of a choice! Apparently this was the perfect attire to represent India’s culture. After all, the salwar kameez was brought by the Moghuls, thus making it not so ‘Indian’. The girls were taught at a very young age that they were important messengers for promoting their country’s culture by what they wear.

This huge responsibility of guarding their country’s culture and countrymen’s honour rested on her slender shoulders. It made her existence so much more important. She fulfilled her responsibility tenaciously. She could not invite any man’s attention by showing any part of her skin and thereby pollute its purity. She used to find a great sense of satisfaction by covering every inch of her flesh, and felt proud that she could not let any other person ‘prey’ on any part of it. She believed that her body belonged solely to her and would subsequently belong to the person she would marry. She was thrilled with the idea of being able to preserve her body (as if it were some kind of pickle) for herself so that she could righteously hand it over to the person she would wed, if not the one she would love.

She would take great lengths to cover the shape of her hips that were revealed in the crisp cotton saris; and those dozen pins, along with holding her sari together, held also her chastity. In all modesty, she knew she was capable of turning heads with her impeccable dress sense. She used to have a huge fan following in the college (an only-women college, mind you!), and some random girls would approach her to compliment her on her cotton saris and simplicity. She knew that her popularity was stifled in those perfect pallus and that she had to now live up to that image, and she therefore added more starch to her cottons and broadened her pleats to look the part of the Simple Good Girl. Neither did she let the sari fall off her shoulders nor the image off her crown!

Then came a time when this small-town simple Sati Savitri-esque girl moved to a big city. Sucked into city fashion, she couldn’t resist skirting sinful hemlines and being trapped in T-shirt tapestry. All her sanctity theories about clothes were thrown in the trash for good. In the process, she happily shed her desi avatar by shedding her saris and proudly embraced the ‘modern’ attire. True to the adage ‘when in Rome, do as the Romans do’, she transformed herself to meet the demands of the city and its style and put on her sundress and sunglasses. After all she did not want to be called a small-town girl. She loved her new label of the ‘young, bold, modern woman’ and thought she could best live up to it with her clothes. Along with her saris (though not because of them), she slowly started to shed some of her inhibitions as well, and started to realise that her body belonged solely to her and needed no kind of patronage from anyone else.

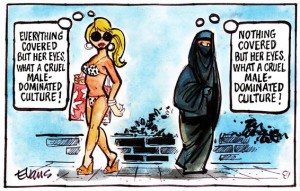

She also understood that no amount of cloth could cover her ‘chastity’. Women were raped or abused or sexually harassed or groped or stared at whether they wore a sari or a skirt or a burka or a bikini. It didn’t seem to matter what she wore to claim her body as her own when the world seemed to think that a woman’s body was common property. She could feel the stench of capitalism mixing with that of sexism. She wanted to fight it away with all her grit and guts. With time, her new fashion code became feminism. This, too, she wore with pride.

She deliberately chose a new wardrobe that had nothing to do with pinks or florals, hanging bows or silky satins, frilly frocks or high heels, corset dresses or body hugging blouses, glitters or shimmers, broaches or slings, blushes or nail paints. She thought they were all too feminine and would make her look like a ‘delicate darling’. She had to look like a ‘feminist’, not buckling down to the frills and thrills of sexism, she thought. She made an effort to dress up not to look like just a ‘pretty thing’, and believed in dressing ‘modestly’ in order to be taken seriously.

While she was busy smashing patriarchy and flagging rainbow colours, little did she know she would be swept away by the colour of passion. Her life suddenly went topsy-turvy when she met a man intriguing enough to grab her attention. She enjoyed the conversations and the connection. She thought she was close to finding the love of her life, well, almost. Almost, until one day she came to know of his fashion mantra for women. He liked it all ‘ladylike’ – prim and proper, lacy and velvety. He had a fetish for manicured tips and toes, baby-doll lingerie and glittery stilettos, to the extent that he fantasised about women wearing fancy lingerie and heels in his bed! That was such an appalling influence of pornography, and absolutely sexist according to her.

Except for his horrifying fetishism, he seemed such a sweetheart. So she tried to avoid conversations surrounding any of his bizarre whims and fancies. But then she was showered with all those ‘girlie’ pretty things as gifts by him. She didn’t know what to do with them. She would end up looking like one of those Victoria’s Secret models on a ramp (not exactly though!). It was all too ‘anti-feminist’ to dress up this way, as they conformed to patriarchal beauty norms and would objectify her, she thought,. She point-blankly refused them and broke his heart a little.

He then asked her, “So what do feminists wear?”

That got her thinking!

Could a modestly dressed woman be called more feminist than a sexily dressed woman? Does putting some makeup on and buying into mainstream beauty norms make a woman less feminist? Can a woman wearing a Fabindia kurta claim to be more feminist than one wearing a sari with pallu on her head? Is there an essential style of clothing to make one look like a feminist?

All her life, she has only attire-abided to be able to live up to an image she thought she should fit into: The Simple Girl, The Modern Girl, The Feminist. Unwittingly, she has been typecasting an outfit into an image and dressing accordingly to become that image. Dressing up to a new image while shedding the old one.

She thought that even though people tend to perceive and judge others based on their attire and appearance, this should not be the way to perceive others, or for us to groom ourselves. She realised that appearing a certain way doesn’t necessarily mean that the person is that way, and that it is unfair to define someone based on their attire, and to let ourselves be thus defined, too.

How to dress is a personal choice, and must continue to be so. In no way should it be dictated. One should wear what one wants to wear rather than what one is supposed to wear, to be able to dress up and shake off various layers of judgments.

Photo Credit: Wikipedia