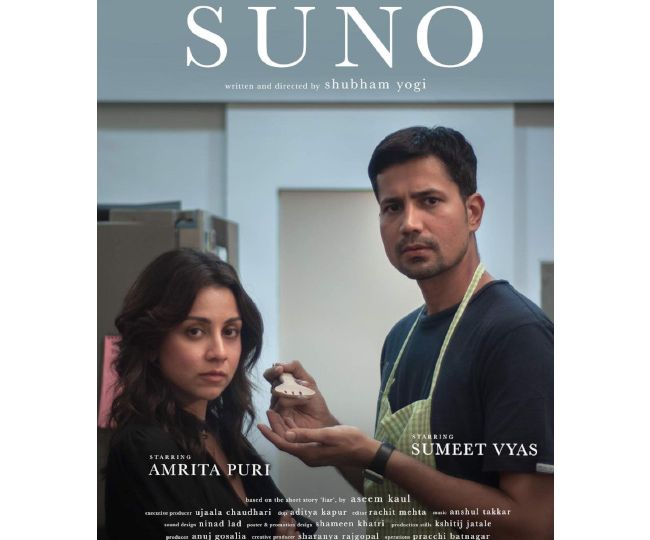

The concept of what consent, and in turn, its violation exactly is, has been pretty unclear to many of us, especially because of the lack of communication around it. There may be situations in which a person’s responses might not be unquestionably equated with consent. Is consent merely a ‘yes’ or does one need to look for other cues to make sure their partner wants the same thing as them when it comes to intimacy? Directed by Shubam Yogi and released in 2019, SUNO, a short film presented by Terribly Tiny Tales, starring Sumeet Vyas and Amrita Puri, asks these very questions and addresses the complexities of such a situation in less than 12 minutes.

Vyas and Puri play a couple in an equal marriage – they engage in open, humorous conversations about sex, he cooks his wife’s favourite dish as she comes home from work, and they complain about how the prying “middle-aged women” living in their building do not understand the dynamic the couple share. But when an ‘adventurous’ sexual encounter between them causes the wife to end up with a black eye, the mark becomes visible evidence of what the world interprets as domestic violence. The couple dismisses these accusations; after all, they are a model ‘perfect, married couple’. However, when a neighbour invites the wife to a support group meeting for victims of domestic abuse, she reluctantly attends. It is then that her stance on the situation changes and she re-evaluates her position. Amrita Puri effectively portrays the wife facing a dilemma. She is forced to choose between avoiding what happened to her to maintain peace in her marriage or confronting her husband for what he did and risk being perceived as an “inconvenience”.

The husband, though, makes jokes about the situation and is nonchalant about what has happened. Sumeet Vyas brings a sense of ease and charm to the character of the seemingly progressive husband. He makes you believe that the allegations of domestic violence made by everyone are too baseless for him to even dignify with a reaction. As the audience, you tend to side with him for most of the film, as he keeps reminding his wife that he hurt her “accidentally”. But within the course of the film, you see him becoming aggressive as his wife confronts him with accusations of hitting and raping her, instead of trying to understand why she’s making these accusations.

He shouts at her, instructing her to not meet with the support group anymore, almost implying dire consequences if his wife doesn’t listen to him. When she protests, he asserts, “I’m your husband!” It is then that you understand that he, too, is a misogynist; he just does not show it. He is probably not far from being proud about ‘allowing’ his wife to work. It’s also at this point that you notice how the husband has been established as a bad listener from the very beginning of the film. In the opening scene itself, he’s shown to be too busy on his phone to listen to what his wife has to say about an encounter with a “judgemental creep”. Later in the film, when his wife tells him about the strategies that some women experiencing domestic violence use to protect themselves, he rolls his eyes with sheer lack of empathy and exclaims, “That’s depressing!” You realise that his dismissal of the accusations of domestic violence stem from his firm belief that he is not capable of hitting his wife, despite what his wife may have to say. Therefore, it isn’t surprising that he hadn’t paid heed to his wife’s unwillingness to engage in sex. However, the audience and the husband are collectively surprised when he realises this – perhaps because, just like him, we were also led to believe that he’s a ‘nice’ man who would never hurt his wife.

By exploring the nuances of consent, SUNO portrays the concept clearly – it is not consent unless the individual in question explicitly agrees to what is being proposed. What the other person needs to do is to listen. The husband may not have wanted to impose his will on his wife, but his sheer lack of knowledge about consent is reflected in how he also did not deem it important to pay heed to his wife’s lack of willingness. The title of the film in all-caps pronounces and re-emphasises this very fact, forcing us to question what our conception of ‘modern’ and ‘progressive’ is, and the lies we tell ourselves to avoid confronting uncomfortable truths that often stand bare in front of us.

Cover image: Film poster of SUNO taken from IMDB