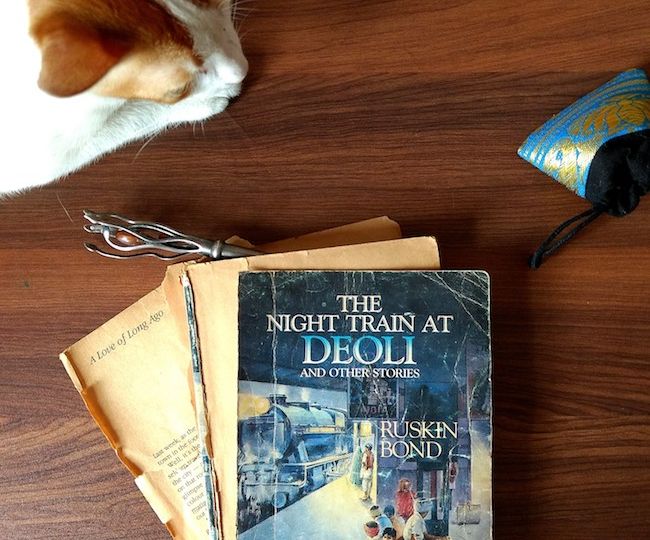

The Night Train at Deoli and Other Stories is a 1988 anthology of Ruskin Bond’s initial writings for adult readers. This column, however, is neither a critical review of the book nor a ballad of Bond’s praises. I merely reminisce about the odd set of events that led me to inherit this book, and find in it an unexpected yet wholesome home for love, limerence and longing.

Home I

For the longest time, tall stacks of books lining the walls occupied greater square footage than actual furniture in every house my parents inhabited. The family album still has crusty pictures of distant relatives sitting on the floor, leaning on a precariously organised exposed ‘book wall’. The books found assigned crevasses in a second hand wrought iron cabinet with glass shutters only when my mother threatened to set them all on fire. When I was twelve, I found The Night Train at Deoli and Other Stories in the bottom shelf during the summer vacation. Perplexed by the fact that my parents somehow missed the anthology even as I was made to complete the Ruskin Bond omnibus just the month before, I swiftly skimmed through pages. It seemed rather insincere to not thoroughly read the book given the expanse of Bond’s children’s literature to which I has already been exposed. My parents, much to their later dismay, weren’t around to censor my reading of the book. By the time my father could tactfully take the book away from me upon his return, I had reached page 238. Not knowing that I had just finished “Love is a Sad Song”, the story of a sensual summer romance between a sixteen-year-old girl and a thirty-year-old man, Appa slid the book into an inaccessible back row of the bookcase and told me that I could read the book after I finished school. It was of course a tad too late for that, but now it is almost endearing to think that my father actually thought my sexual naivety was going to last that long.

While I effectively excavated the book to complete the last five pages, Bond’s tales of love, loss, and lust still remained slightly outside my cognitive ability for the next few months. When I completed high school and managed to sample all three of those emotional whirlpools, my father somewhat ceremoniously handed me his copy of The Night Train at Deoli. He sat me down to ruminate about the origin of the book, and in that ephemeral moment the text acquired history.

As I run my fingers through the brittle pages of the book in this moment, weaving together memories of this text, it feels like a poetic anthropology project. Appa’s copy has way too many chai stains, something I did not notice fourteen years ago in the frenzy of gobbling up amorous words. I also probably didn’t have the affective patience to make these aesthetic notes. But, as I browse through loosely hanging pages which expose the feeble spine of the book, I can see tobacco crumbs, fossilised yet somehow fragrant. Appa didn’t smoke, but it was borrowed by a hostel mate who seems to have quite enthusiastically used the book as a surface to roll his cigarettes. I don’t think Appa finished it either. The first quarter of the book has numerous finger imprints, while the rest of the pages seem rather devoid of human contact, except for the receipt for the purchase, still stuck by page 118. I remember Appa telling me that he bought it out of the periodic stipend he received as a part of his senior research fund to buy academic texts. He took great pride in actually buying the books, and not submitting faux receipts as his peers did. But, I suppose The Night Train at Deoli didn’t quite qualify to be of great sociological significance to his university bursar. While the text was loved, lent, and left midway, I can completely imagine it sitting ornamentally next to my father’s portable typewriter under dim yellow light. However, while the book was passed down to me as an heirloom, it became the real, yet utopic extension of ‘home’ for another set of reasons.

Home II

In familial homes, romantic love is often introduced through cautionary tales reiterating the logistical practicality and social acceptability of finding a partner. The Night Train at Deoli offered a textual abstraction from the empirics of love. In his writings, Bond somewhat normalizes the type of love that is dreamy, and often delusional. In the past decade, as I grew older and was expected to make “wise” emotional investments, I often went back to the text to rationalise my romantic irrationalities. Friends would repeatedly remind me that moderately beautiful women desired by other moderately beautiful people don’t need romantic fables such as the ones I liked weaving together. However, I came to cross paths with two women who normalised the naivety of delusional love, just as in Bond’s writings. The first was a temporal soul sister who would dedicatedly write love notes behind bus tickets, hoping to leave them behind after a night with the men she desired, but was yet to seduce. The second was Sylvia Plath, with her poetic sulking about the love(s) she wilfully and gleefully deluded herself into.

I dreamed that you bewitched me into bed

And snug me moon-struck, kissed me quite insane.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

God topples from the sky, hell’s fires fade:

Exit seraphim and Satan’s men:

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

I fancied you’d return the way you said,

But I grow old and I forget your name.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

I should have loved a thunderbird instead;

Al least when spring comes they roar back again.

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

– Sylvia Plath, Mad Girl’s Love Song

While Plath parallels the exhilaration of romantic delusions with some self-scolding, the two women, in consonance with Bond’s anthology, never necessitated even momentary sobriety for me. To add to the fuel, long-term partners indulged me in my manic limerence for others and took active interest in my sifting sites of fixation. Even as I had to time and again let go of these friends and lovers (even Plath, because of clinical depression), the ragged pages of The Night Train at Deoli stayed with me as the world around tried to dissuade me from love that was deviously dreamy with a dash of harmless delusion. Bond didn’t emphasize actualizing infatuations or confessing prolonged crushes, because he allowed his protagonists delusions with self-awareness. The characters in his stories were often circular in their approach to romantic admiration, yet comforting in the ways they saved love from travesties of everyday pragmatism. Concluding The Night Train at Deoli, the central story of his anthology, Bond writes:

The Night Train at Deoli and Other Stories (1988) Penguin Books, pp. 56

This excerpt from the concluding section of The Night Train at Deoli has remained the summated story of all my love stories. I like how the protagonist is not desperately longing for his object of limerence, but simply hoping and dreaming of myriad romantic possibilities. Coming back to finding a utopic home within the narratives from The Night Train at Deoli, the book wasn’t necessarily an escape from what constituted the material home, but rather an assurance that love can have plural possibilities, and so can what comes to be ‘home’. While some longings might be actualised, the text was an affirmation that love could still find home in inventive imaginations which didn’t have to follow regimented scripts of romance.