“A woman’s vocabulary exists, linked to the feminine universe. I feel this occasionally in that I am inspired by a certain number of attractions, subjects which always draw me rather more than they would if I were a man…I don’t want to make feminist cinema either, just want to tell women’s stories about women.”

– Agnès Varda[1]

When I started out telling stories through film, I followed my instinct more than anything else. It would feel like I would come across stories by chance, never realising the many conscious choices I was making at every step. I was just happy to have found something I loved to do. As the years passed on, it became obvious that the stories I chose, the ways in which I engaged with my ‘characters’ and, very simply, my work ethic, was not in line with most others. I was not okay with treating people as merely faces who would deliver bytes to the camera, but I learnt to do it anyway. I dug up case studies that would fit the ‘brief’, and sometimes even put words into their mouths. There was a stark difference between these experiences and my own film practice, and it could not be adequately explained by the difference in commercial work versus passion projects. There had to be more to it.

As I began to read about feminist methodology in academic research, it felt like I finally found words to articulate my experience. Feminist methodology addresses problems in traditional forms of scientific and social research, such as giving high regard to objectivity and rationality, and the power equation in the researcher-subject relationship. Feminist scholars argue that the idea of objectivity and rationality works as a stand-in for the male perspective, and is essentially a tool to ‘otherise’ and objectify the people being studied. The anonymity of the researcher allows for biases to creep in without any accountability. On the other hand, the lack of agency with the research participant creates a false objectivity, and an unequal, exploitative relationship.

Standing behind the camera, with a microphone in one hand, I have felt this power imbalance first hand. The camera may humanise the person in front of it more than a text analysis would, but the modes of production remain in someone else’s hands. Despite these shortcomings, I believe that the documentary medium aspires to be a feminist one. Though it is also used for objective and masculine narratives, the form offers ample space for ethical engagement and subjective storytelling. I find inspiration in Richa Nagar’s work on storytelling and co-authorship, as explained in her book Muddying the Waters: Coauthoring Feminisms across Scholarship and Activism (2014, University of Illinois Press). She looks at co-authorship as a mode of sharing authority with her ‘research subjects’, and considers translation an ethical responsibility.

“What is needed…are stories of building deep relationships and of undertaking long, hard journeys with those who become our ‘research subjects’; stories of how we live, grow, learn, and change in and through those journeys. Sometimes the details of specific events and encounters in these journeys may be unutterable, or it may be unethical to repeat them; still, the stories of the journeys themselves are valuable knowledge.”

– Richa Nagar[2]

During an audience discussion after a recent screening of my 2018 documentary film Daughter of Nepal, an audience member remarked about a tender moment shared between the protagonist of the film and me (the director). They said that they had never seen anything like it. This made me recall how difficult it had been to put myself in front of the camera. It was a last-minute decision made during filming, only to ensure the comfort of the film’s protagonist. I struggled with the edit of the film for months because I kept trying to find ways to remove myself from the film, only to fail in the end. This creative choice, or lack thereof, shaped the film, and was appreciated by all. Now equipped with the tools of feminist methodology, I am able to decode the reason behind this choice. It was an attempt to level the playing field.

Documentary storytellers rely heavily on oral history traditions – using interviews to document people’s personal knowledge of past events. This mode of documentation has helped bring to life vivid accounts and viewpoints of the marginalised and oppressed. Oral history has also increasingly become popular in the feminist movement, as “a way of understanding and bringing forth the history of women in a culture that has traditionally relied on masculine interpretation.”(The Interview: From Formal to Postmodern, Andrea Fontana &Anastasia H. Prokos, 2007, Left Coast Press. Chapter 5.)

A Thin Wall, a documentary film that I co-produced with director Mara Ahmed, is a collage of mostly women’s voices about the partition of India. I often get asked if it was an intentional choice to present predominantly women’s stories in the hour-long film. During the film’s edit, when we went through the several hours of interviews gathered over the years, we noticed a marked difference in the quality of the content. Most of the men we had spoken with had told their stories with facts and figures, while most of the women had spoken through incidents they had witnessed and described how they felt in those moments. So, for us, the only choice we had was to use voices that were personal and moved us deeply – the voices that had been overlooked in the mainstream documentation of the event.

Feminist methodology provides a guiding framework for ethical documentary filmmaking, though I do still believe that the ones with the camera will always have the upper hand. As documentary filmmakers, we ask others to share their lived experiences, private memories, and their deepest, darkest thoughts. We manipulate these stories that are sacrosanct to them. Even if there is no fair answer yet, it is important to ask, “What do they get in return?”

[1] Alison Smith. 1998. Agnès Varda. Manchester University Press. Page 92.

[2]https://quote.ucsd.edu/sed/files/2017/05/Elizabeth-Dauphinees-Interview-with-Richa-Nagar-Journal-of-Narrative-Politics-Vol-2-No.2-March-2016.pdf

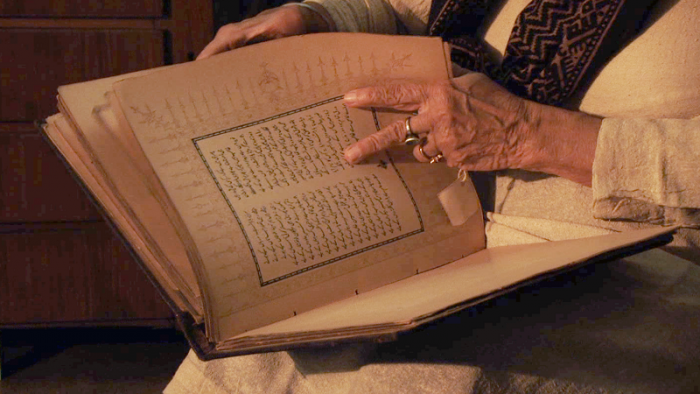

Cover image: Jitender Sethi sifts through the pages of her book, courtesy of the author