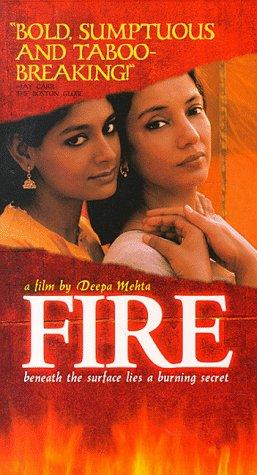

When I think about the sexuality education I received as a young person, I recall sitting in my high school health class as my teacher explained the dangers of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) to us. While the traditional sex education I received in school (consisting of lessons on safe sex and how our bodies change during puberty) was important, it focused on sexual health and anatomy with a sole focus on protection rather than pleasure. Many associate sexuality solely with the act of sex and one’s sexual identity, but in reality, it is so much broader than that. Sexuality is a core aspect of our lives from birth and understanding our sexuality is a key component to our wellbeing. In the absence of Comprehensive Sexuality Education (CSE), the sex education I received left me with an incomplete picture. What encompasses sexuality is also ever-evolving; it constitutes the relationships we have with others, the people we might be attracted to, and the norms within our communities and cultures. This is not traditionally explored in the American education system I grew up with, but it was the education that I desperately needed as a young person. Consequently, I searched for answers to my sexuality-related questions through other means, as young people often do. As a movie lover, this meant turning to films. One of the most impactful films for me was Fire (1996).

Written and directed by Deepa Mehta, Fire is often regarded as the first mainstream Bollywood film to feature a ‘lesbian’ relationship. It follows two women, Sita (Nandita Das) and Radha (Shabana Azmi), who are the wives of brothers in a typical joint Indian family. Sita is a wide-eyed young woman who has just been married to Jatin (Javed Jaffrey) and goes to live with him and his family. This includes Jatin’s older brother, Ashok (Kulbhushan Kharbanda), the patriarch of the family, and his wife, Radha. It’s quickly established that happy marriages have not come to define this household. Jatin only marries Sita out of obligation to his family but is in love with another woman. Additionally, Radha and Ashok have not been physical for years. Several years prior, it was discovered that Radha cannot bear children, leading Ashok, a devoutly religious man, to take a vow of celibacy, which Radha goes along with reluctantly. In the midst of these two unfulfilling marriages, Sita and Radha form a bond, which develops into a romantic and sexual relationship.

This film is a classic in the field of sexuality, and while it is highly regarded in India, as a young queer American, discovering this film was like finding a rare gem. As a closeted teenager, I was desperate to see representations of myself on screen. Fire served as a seminal piece of media in my life for that reason, not only because of its queer themes and normalisation of LGBTQ+ relationships but because of how it normalises the pursuit of pleasure as a fundamental part of us, and not something we should be ashamed of. One of the most important facets of sexuality education is that it be pleasure-affirming, and not until I went to college and started studying sexuality more in-depth did I learn what this term meant, and realise why Fire was such an important film for me to see as a teenager.

Fire’s primary message is that seeking desire and pleasure, particularly in the context of queer relationships, is perfectly okay. At a time in which expressing desire and pleasure even in heterosexual relationships was considered taboo, presenting these themes through queer characters was especially radical. In the climactic scene, Radha is confronted by her husband for having a relationship with Sita. She is unapologetic about her actions and feelings toward Sita. In a chilling monologue delivered brilliantly by actor Shabana Azmi, Radha says, “You know that without desire, I was dead. Without desire, there’s no point in living. You know what else? I desire to live. I desire Sita. I desire her warmth, her compassion, her body. I desire to live again.” With this line, Mehta is telling the world that it’s okay to have desires and that seeking pleasure in life is not selfish. At this point in my life, I had just started to accept my sexual orientation, but I still felt so much shame around my sexuality, which stemmed from a lack of understanding of how ‘normal’ my desires were. Seeing a character like Radha, who previously had attached so much guilt to her desires, finally exercise her right to pleasure, did a lot to lessen the shame attached to my own sexuality.

One of the primary reasons why I was uncomfortable with my sexuality growing up was because I felt it was incompatible with my culture and religion. I grew up in a Greek Orthodox Christian household, and I had always imagined that I would get married in a church and fulfil the many heteronormative expectations that I put on myself based on what my culture normalised. Although growing up in the United States with a European background is a far cry from being a married Indian woman in the 90s, I still found ways to relate to Sita and Radha.

Fire has a lot to say about culture and received much criticism following its release based on the notion that its display of sexuality was an insult to traditional Indian culture and the sanctity of (heteronormative) marriage. However, in Fire, Mehta conveys just the opposite. Throughout the film, Indian cultural themes are woven in and out of different characters’ storylines. The title of the film itself is an allusion to the story of the Hindu Goddess Sita in the epic, Ramayana. In this story, which is recounted in the film itself, Sita goes through an Agni Pariksha or a ‘trial by fire’ to prove her chastity. She goes through the fire, comes out unscathed, and is thus determined to be pure. During the film’s climax, Radha goes through her own Agni Pariksha. While being confronted by Ashok after he discovers her relationship with Sita, Radha catches fire from the stove and is subsequently left to burn. At the end of the film, Radha appears to have emerged from the fire alive and is reunited with Sita. Mehta uses the story from the Ramayana as a way to show that Radha is still pure even after having a sexual relationship with Sita, making the argument that one is not necessarily impure for pursuing pleasure or for expressing queer desires and intimacies.

I would argue that rather than criticising Indian culture and tradition, Mehta is using it as a medium to promote her message of normalising queer female sexuality and in a way, celebrates Indian and Hindu culture. Mehta’s criticism is not about culture itself but about how people use culture and traditions to repress others’ autonomy over their sexuality. Through this ending, Mehta perfectly blends culture and sexuality by using a cultural example of the Agni Pariksha in the Ramayana to make a statement that is unabashedly pleasure-affirming. As I know now, sexuality and culture are not conflicting forces. Rather, they are two factors that help shape our identities. I can still choose to hold on to my cultural values, while embracing my sexuality because they are not mutually exclusive entities. This is the message that I was not being taught in school but desperately needed to hear growing up.

I can go on and on about the brilliance of Fire and its significance to my life as well as to those of many others, but I think people’s relationships with this film point to something much broader about CSE. In my case, the fact that I was drawn so strongly to this film speaks to how important of a role media plays in shaping our views and how it has an incredible power to teach us things. This film also speaks to the dangers of not understanding one’s sexuality. Fire was so impactful for me because, in many ways, it served to fill in gaps in my understanding of sexuality. I think about how much more self-assured I would have been growing up had I been having conversations about the complex connections between sexual identity and culture in a school setting. While there are many great films and TV shows capable of teaching us lessons, this should not be where a young person goes to learn about sexuality. Rather, films like Fire can be used as tools by educators in the process of imparting CSE to young people.

Cover Image: IMDb