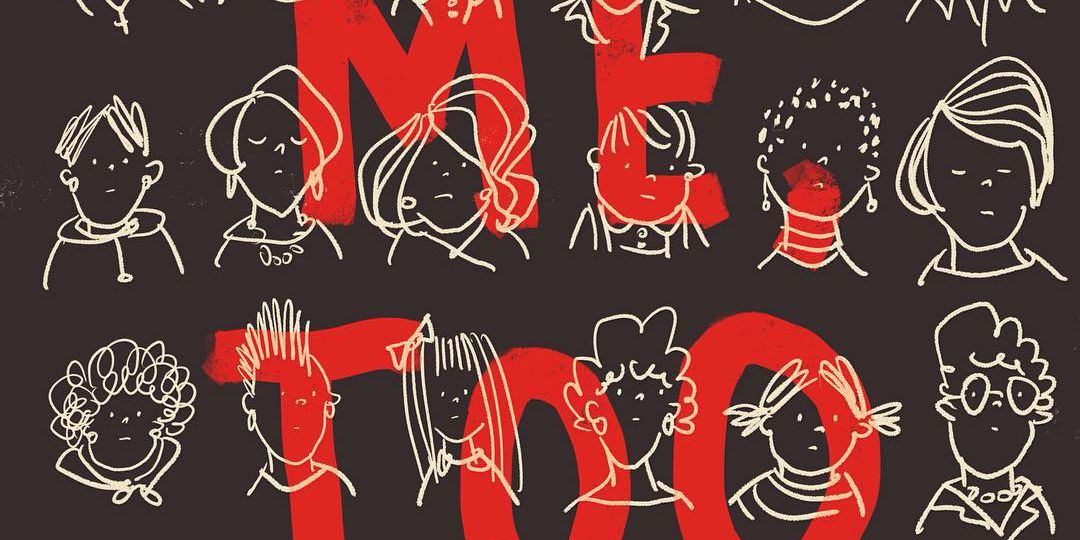

As I sit to write this piece, #MeToo is trending online. People across the world who have experienced sexual harassment, abuse and assault are identifying themselves online with this simple hashtag. I often wonder if all the stories behind the hashtag tumbled out, how many white picket fences would be destroyed?

In early October 2017, The New York Times published a report exposing Harvey Weinstein, a big shot Hollywood producer, as a sexual predator. The backlash has been swift. Since the first report, dozens of women have come out with their personal stories, the producer has been fired and criminal investigations are underway in two countries.

A powerful man who used his professional success and the power that comes with it to harass and assault dozens of women has fallen. The magnitude of this exposé is reverberating around the world.

I want to draw the reader’s attention to what Mr. Weinstein said in his apology letter published by The New York Times. In the very first line he says, “I came of age in the ’60s and ’70s, when all the rules about behaviour and workplaces were different. That was the culture then.” This is true. What is also true is that this is no defense.

I have often felt the generation gap to which Mr. Weinstein alludes. In the professional environment, my experiences with older men neatly fall into two categories. One section of older men, no matter what, do not want to be seen alone with you. They would not dare to conduct a one-on-one meeting behind closed doors. They don’t want to be in situations that can be misconstrued in any way, and in light of the extensive sexual harassment prevention trainings meted out, these folks cautiously cover their bases lest someone accuses them of sexual misconduct.

The other set of older men is less guarded and fails to recognize the misogyny embedded in their beliefs. Sample this: a male colleague was sharing with us who all he met and what talks he attended at a conference. When he spoke about the male scientists he encountered, he only commented on their work. But the one female scientist he talked about was introduced as “a woman in excellent shape for her age” and “her science is not bad”, in that specific order. It is gut-wrenching to know that one’s looks are influencing one’s audience more than one’s work. She has a distinguished career spanning thirty years, but her looks came before her work!

At a conference I attended, the professors were asked to present a mock talk imagining how their field of work would evolve in the next fifty years. During one of the talks, a professor presented a scenario in which the work done by a group of scientists would take the field by storm until it would be proved incorrect by another competing group. Of course this would all have been harmless fun had he not presented the first group of scientists as young, blonde, blue-eyed women who stood corrected by older balding white men in science. This picture made me cringe while the audience chuckled. It also made me wonder how a well-educated man and accomplished scientist was blind to his own prejudice. Why was this humorous to him? I asked myself, did he see in that story what women saw? Probably not.

These men I talk about have one thing in common: they came of age in the ’60s and ’70s. Both experiences recounted above point to a certain discomfort these men feel around the women who work with them.

The ’60s and ’70s was an era when sexual harassment at the work place was unchecked and pervasive. The first generation of women in independent India was beginning to work. A lot of these women chose to stay quiet about the harassment they faced lest they lose their family’s ‘permission’ to work. ‘Aisa hi hota hai’ (This is how it is): they sucked it up, looked the other way and moved on. Their silence was for survival, to create a place first for themselves and then for future generations of Indian women to follow.

As a teenager growing up in Delhi in the mid-nineties, every girl I knew had been inappropriately touched, fondled or rubbed against. Some of us had been stalked. I remember in school, teachers would spend time going over how, if someone started to follow us, we were to manoeuvre our escape.

The same teachers also promised us that they were raising sensitive boys – sons who were more respectful of women, who were supportive of working women and who understood that gender stereotypes were slowly but surely on their way out. At work I have always felt more comfortable around men my own age and I attribute it to the sensibilities of the mothers who raised them. I also attribute it to their willingness to be engaged with the world we live in, when more and more women are coming out with their own sordid stories. I see in them a sense of shame and a desire for a better world.

The generation of the ’80’s and ’90’s never learned about ‘sexual harassment’ as a term; we never had that language. We never knew we could go and report someone for harassing us. In fact, we grew up in the culture of victim blaming. Awareness about our own rights came with time, as we stepped out and took our first jobs. In light of that, it is heartening to see children today learning from a very early age the difference between good and bad touch. It’s no longer about the clothing they wear.

The turning point when Indian women moved from silence to speaking up with a united forceful voice was the ‘Nirbhaya’ rape case of 2012. It rocked the very core of the ‘aisa hi hota hai’ victim-blaming middle class. On a personal note, within my microcosm, it was the first time people were talking openly in their homes – fathers with daughters, aunts with nieces, male cousins with female cousins, younger women with older women. The magnitude of the problem was becoming evident. A younger male twenty-something cousin confided in me that for the first time, he was becoming aware “of what women went through”. He told me that watching all of our pained reactions at home was difficult for him, and that he had never realized the harassment an average woman faces on a daily basis. After every case before ‘Nirbhaya’ I had found myself arguing against victim blaming. But the events of December 2012 changed the way the Indian middle class conversed about sexual assault and harassment at home. This was phenomenal.

Fast forward to 2017. The exposure of a famous powerful man as a predator through investigative journalism coupled with a thriving social media means that more and more women are opening up, sharing personal stories and holding a mirror to society across the world. The Weinstein story may have played out locally in its country of origin but in its flavour, tone and tenor it is terrifyingly universal. Ask women

This is why #MeToo trended. The numbers are staggering. Facebook has said that within the first 24 hours, about 4.7 million people had engaged in the conversation. Within that same time period, 68000 tweets were posted in reply to the Alyssa Milano tweet that started it. Indians have spoken up in large numbers in comparison their South Asian counterparts and India is the only country where more men (63%) than women tweeted it, according to analysis by data scientists. What that means, is difficult to say.

It has been hard to read through some of the detailed accounts. A five year old made to caress a penis in a public bus, a pre-pubescent ten-year-old’s fledgling breasts pinched hard in a crowded market, hands under skirts, incessant demands of ‘please be my friend’, forced kisses, beatings and more. And for most teenage girls, this abuse was probably their first sexual experience.

Older Indian women have been quieter. They may not open up online but I doubt they can avoid this conversation in their homes, with their friends, family and children.

In the two weeks since #MeToo started trending, noteworthy conversations have been unfolding online. In solidarity, men are supporting women who are coming out as survivors with #IHearYou and #WithYou, they are speaking up about their own complicity in the current social scenario and vowing to make a difference, and apologizing for feeding the patriarchal monster. They are also sharing their own stories of abuse.

Not everyone, however, is taken in by #MeToo. Some women feel that they shouldn’t have to make a public show of their pain for their suffering to be acknowledged. For others, sharing their story in such a public fashion exposes them to further online harassment from those who think of the hashtag campaign as a sympathy-seeking movement. Then there are those who are downright unimpressed, feeling that it unfairly casts sexual harassment as a man vs. women problem.

All of this is significant. It highlights the complexity that exists around online campaigns like this one in general and our collective societal approach to the issue of sexual harassment and abuse in particular.

My older male colleagues may never understand why a casual comment about a woman’s body is wrong. But, I hope, perhaps reading #MeToo helps. We cannot afford the tragedy of silence anymore. We are speaking up publicly. We are developing a vocabulary to share our experiences of abuse and harassment. Bit by bit, the silence is fading.