Let me begin with a confession. I have always loved the idea of marriage. What is one to do when one’s politics are so at odds with one’s pleasure! But then politics and pleasure are not always so distinct. And so, after having seriously contemplated a career in wedding choreography (yes it’s a thing!) and wedding video making, here I am, still fantasizing and watching everything about marriages and weddings from the side.

It was for my generation of movie-goers that marriage was rediscovered on the silver screen as the bastion of the great Indian joint family (and friends). In 1994, Hum Aapke Hain Kaun (HAHK) turned all North Indian upper class, upper caste weddings into a string of endless, and unbearable “family performances”. Which brings me to my second confession, I loved the film when it released and wished all marriages would be just like that. The film quickly became the north Indian wedding template, however, serving as a warning to always be careful in my wishes.

What fascinates me about marriage is not the obvious romance of the ever after, but the hidden pleasure of the here and now. The romance of Hum Aapke Hain Kaun wasn’t between the Bride and the Groom, who like “Ram Ji” were pious, ideal and sexless. The story belonged to didi ka dewar (sister’s brother in law) and dulhe ki saali (Groom’s sister in law), and the accompanying nok jhonk (dalliance/ flirtation) between the uncles and aunts, among the domestic help (one must always carefully maintain caste and class lines in side stories) and flirtation between the samdhi and samdhan which was curiously suggestive. An overt celebration of love relationships, and the covert sanctioning of sexuality are part of not just marriage as a social system, but also as a community event. But even before Tuffy saved the day in a great shift from Ram ji to Krishna[1] at the end of the film, marriage has been about the ras (pleasure), raas (amour) and risqué. And nowhere is the expression of pleasure, desire and sexuality celebrated more than in women’s songs that accompany celebrations, particularly those of marriage.

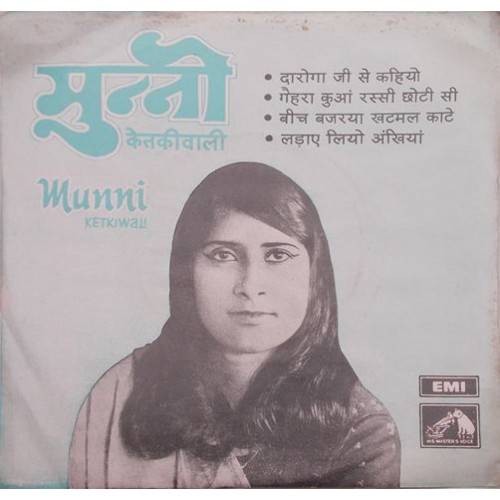

Munni Ketki Wali is a gifted singer with just such a repertoire of songs who I discovered thanks to hours of YouTube surfing and the good folks at TARSHI. There is almost no information about her life and work online, except in some YouTube comments under her songs. With albums released in the 70s, 80s and 90s, she combines the musical style of the sixties with Bhojpuri tunes, offering a wide selection of folk, film inspired songs as well as pop. More recent blatantly sexual video accompaniments to her music pale in comparison to the pictures of Munni, clear eyes, confident gaze, looking directly at her audience, on the covers of her albums that feature in the videos of many of her songs on YouTube. [here I suggest inserting her picture] She sings of her Samdhan’s sexual escapades and desires with taunts, jest and perhaps jealousy. Innocuous, mundane and often playful melodies combine with lyrics rife with witty innuendo and bawdy humour. Ketki Wali’s songs reveal what Hum Aapke Hain Kaun had to conceal and sanitize. And so, having found my politics and my pleasure all in one place, I urge the popularization of Munni’s music as a way of revealing marriage as a community celebration of sexuality. A flamboyant march where people wear their sexuality on their sleeve and come out in a loud display of desire to take over public space. Almost like a jagrata (a Hindu ritual, consisting of all-night vigil, songs and dance in honour of a deity), or a pride march perhaps. Well, almost.

A woman who sings of desire and not duty, may well be banned by the censors. It seems obvious, not just in light of the current fetish for bans, but historically, whether women reveal the hearts in their choli or enjoy being called sexy[2]. As Shohini Ghosh pointed out in her writing[3] on the song Choli Ke Peechey from Khalnayak, it is women’s assertions of sexuality and not violence against women that invites censure and ire from the custodians of tradition and culture. Munni Ketki Wali’s wedding songs are replete with women singing sexually to each other, and expressing their desires and narratives in a way that has always been dangerous for patriarchy. Even as one is aware of a larger patriarchal context of cultural production, faced with little information about the production of these songs, one must rely on hope and fantasy. And so here is a Sexy Samdhan Songs collection that brings together community rituals, popular culture and the dailiness of desire and sexuality in our lives… if only we choose to see it! #ShaadiMubaarak

- An intersectional analysis of marriage rituals would be very insightful to understand whether women have the license to be licentious in the same way across castes or outside the savarna However, HAHK would be a very different, and a far more exciting affair if it were Munni Ketki Wali and not Lata Mangeshkar crooning the background score. The celebration might have sounded something like this:

Chana Jor Garam

- Aloknath in Hum Aapke Hain Kaun could limit his crooning to expressing dilemma in these words:

“aaj hamaare dil mein ajab yeh uljhan hai

gaane baithe gaana, saamne samdhan hai..”

(I have this strange confusion in my heart belies

I sat down to sing, samdhan appeared…)

Munni has no uljhan (confusion) about singing her Samdhan’s praises:

Baithey Hue Ko

- Munni’s questions to her Samdhan are direct, unabashed and full of humour. In my alternative hum aapke hain kaun, this is how the two would have discussed the menu.

Kela kaise khaogi:

- It’s also all about consent. So when it is given, it must be appreciated and celebrated appropriately.After all,

“yeh shaadi ki hain fuljhadiyan, lagti nahi ismein hathkadiyan

tu bhanwara ban ke ras le le, tere hi liye hain pankhadiyan.”

(These fireworks of marriage are not to tie your hand

claim the nectar like a bee, these petals are at your command)

- Songs to samdhan are not just about desire but also about jest and taunts kyunki behen, “shaadi ka hai zamaana”(because sister “this is the period/era of marriages”). Innuendo laden aunts are even more hilarious when coupled with the familiar and lyrical melody of this iconic song where Munni replaces love and longing with lust.

Shaadi ka hai Zamaana:

- While Munni’s repertoire includes many odes to Bollywood, there are obvious parallels when she takes on the samdhan as tawaif (courtesan). While Mausam hai Aashiqana is not such an obvious choice, this one, a courtesan classic pleases with shock from the word go

Samdhan ke daak khaane ko:

- I cannot leave out Munni’s folk songs that are not overtly about marriage from this list. While I include them in the interest of profiling her full variety, wedding metaphors find place in her other songs as well. Such as this one about a khatmal (bedbug) that peeks out of the protagonist’s bustier like a bride peeking out of her palanquin on the way to her groom’s house.

Beech bajariya khatmal kaate

- What better song to end this list, than another iconic tune from Bollywood, re-imagined as a narrative of Samdhan’s escapades during the wedding. Do remember though that this is hardly the surface. While there is scanty information about her, a wealth of music and merriment awaits fellow YouTube junkies who would like to go exploring Munni Ketki Wali’s music. The journey promises to be lustful, liberating and very lyrical.

Gaal tera choom ke

इस लेख को हिंदी में पढ़ने के लिए यहाँ क्लिक करें।

This article was originally published in the July 2017: Communities and Sexuality issue of In Plainspeak.

* Samdhi and Samdhan refers to a person’s in laws, specifically the relationship between parents of the two partners in a marriage. The women being“samdhan” and the men, “samdhi”.

[1] The climax of HAHK centres around the family dog delivering a letter meant by the female protagonist for her lover to his elder brother, whom she chooses to marry after the death of her sister who was married to him, as a family responsibility. The dog, Tuffy, looks benignly at the altar of Lord Krishna and decides to deliver the letter to her would-be husband instead, who has no idea about this sacrifice and the affair. He goes on to step aside and get the two lovers married in a happy ending of family love and togetherness. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6oiYd87yKc

[2] Choli ke Peechey from Khalnayak and Sexy Sexy Sexy from Khuddar are two such songs that censors and the public called for banning. Shohini Ghosh in her writing on Choli ke Peechey points out how it is usually expressions of sexuality by women and not sexual attacks on women in cinema that attract attention and become the subjects of bans/censorship. “Sexy sexy sexy” in the song from Khuddar was indeed changed to Baby Baby Baby for all televised broadcasts

[3] Ghosh, Shohini. The Troubled Existence of Sex and Sexuality: Feminists Engage with Censorship. In Christiane Brosius and Melissa Butcher (Eds.), Image Journeys: Audio Visual Media and Cultural Change in India. Sage, 1999. Pp. 235-259.

Cover Image: Munni Ketkiwali (Hindi Geet) – 7EPE 17513