My first ‘date’ was at a festival screening of an understated French-Canadian film that featured a tremendous amount of chatter and Chopin. I qualify ‘date’ because, while I was certainly on the brink of tumbling head over heels, the object of my affection, let’s call her ObjA, was blithely unaware of the romantic hopes that hinged upon our meeting. Afterwards, ObjA said to me, “You don’t fidget, that’s nice. It’s irritating to sit next to someone who fidgets” – little realising that it was with the greatest reluctance I’d let myself breathe, so smitten was I into stillness, so terrified of breaking the moment.

There’s not much I remember of the film, though it gave me a lifelong love of the Raindrop prelude – but I doubt I’ll ever forget its name. For one, we laughed about it so much afterwards (why? Googling it now, I see the description begins with, “A Canadian woman travels to Italy to commit suicide because the love of her life has…” So yes, it was that kind of film). And besides, it’s so fitting, in hindsight, to have myself discover the drama of first love at a movie built on the conceit of seismic shifts: it was called Tectonic Plates.

One of my teachers from college once told a funny story about the hazards of festival screenings. In those days, India’s international film festival, IFFI, was held in Delhi, spread across the city’s theatres, in the nobly socialist hope of attracting audiences that might otherwise never consider going to Siri Fort, the festival’s epicentre. Some of these theatres, however, were also known for their ‘morning shows’, advertised with lurid posters featuring buxom blondes of lascivious intent. It was at one such establishment that my teacher arrived, early one morning, to watch something high-minded in Swedish. Much of his fellow audience, however, had come in expectation of the regular morning playbill, or perhaps in the hope that festival fare would offer greater, uncut titillation. The unfolding Nordic narrative, however, held only disappointment. Restless mutterings broke out in various dark corners of the hall, gathering steam until a section of the audience shuffled to its feet and formed a small procession, in which they marched up and down before the screen, raising slogans and demanding their money back.

I understood their pain, but did not share their convictions. For me, slow-moving films of abstract intent had become the very stuff of romance. Following my success with Tectonic Plates, I was prepared to sit still and barely breathing through the gamut of world cinema, as long as ObjA would come with me. Less often than I’d have liked her to, she did; but more and more, I went anyway, alone. The French cultural centre was nearby and active, so I watched all of Godard, smatterings of Truffaut, Renoir and Bresson; I travelled further afield for Fellini and Kurosawa; I spent a week engrossed in a Bergman festival. I remember embarrassingly little of what I saw. I remember Death and a game of chess; I remember a lot of cafés and cognac and languid conversations, somehow imbued with unbearable consequence; I remember a man painted blue for no fathomable reason except, perhaps, to be unfathomable. Or blue.

What I remember more clearly is the general sense of those films. The sense of great emotions that could not, somehow, be expressed, though they could be talked about and around endlessly. A sense of no particular plot, driven by oddly irresistible narrative force. I remember endings that were never quite clear, but always a little sad, even when they were happy. It may be, of course, that I was watching (mostly) European cinema of a certain type and vintage, and that they shared these traits in common, but I suspect my memories also contain something of what I projected upon the screen, sitting in the dark with only my anguished adolescence for company, hoping against hope ObjA would come.

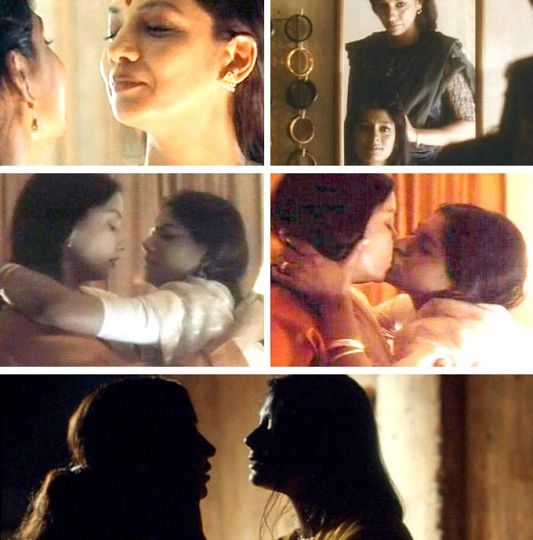

The last film ObjA and I saw together was Fire, a film I was desperately keen to watch, and worried sick someone would catch me watching. The news was full, those days, of protestors who wanted Deepa Mehta’s story of Sapphic sisters-in-law banned – and others who were protesting aloud their proud queerness. I remember staring at a photograph of a group of women marching, one of them holding a sign that proclaimed her “Indian and Lesbian”. The very thought of being photographed thus, of ever holding such a banner in public, made my stomach churn. The only thing worse would be to have ObjA not love me back.

Even to my besotted self, however, it was clear by then that ObjA did not, in fact, love me and never would. I had confessed my love to her, to little effect. She would be kind but she would not reciprocate. Somehow, for six of eight halting, awkward months, we tried to be ‘friends’.

We went to Fire towards the end of this time. A mutual friend came with us. At any other film, I’d have resented this intrusion, but being three women, not two, at this particular screening somehow made it a little less scary. This was certainly not a ‘date’, nor could it be perceived as one.

I wasn’t impressed with Fire; I found it superficial and silly. There was no thrill of recognition, no feeling of risk. But so what? There was thrill enough in sitting next to ObjA in a dark hall, almost knowing it was the last time. There were frissons to last a lifetime in the car ride home, through Delhi’s dark streets, the three of us squeezed in the back seat and ObjA’s shoulder pressing into mine, her hair falling on my cheek.

We got off a kilometre or so from where we both lived, and I suggested walking. It wasn’t very late, but it was winter, and dark, and Delhi’s streets –though impossible to believe now – did once grow empty after nightfall. A car drove noisily towards us and stopped; a man pushed his head out of the window and asked for directions to a local landmark. I hesitated a moment, the way you do if you’re a woman and a man drives up in the dark. Then I pointed and told him which way to go. He drove off, in a burst of acceleration.

ObjA said, “He knew better than your father which way to go.”

She meant, I suppose, that she had been scared. She meant, perhaps, life cannot be lived entirely in the safety of darkened auditoriums, glimmering with beautifully shot scenes; that it has a way, instead, of impinging rather bluntly on our fondest dreams.

Cover image: Movie stills from the film Fire (1996)